28th of December 1879 – the Tay Disaster

| < Bouch’s Forth Bridge | Δ The Queensferry Passage | The Forth Bridge > |

Thomas Bouch, soon to be Sir Thomas, was on the pinnacle of his profession. His working life ambitions unrelentingly falling into place. His eminence in the railway engineering sphere was unchallenged, and work had begun on what even he acknowledged would be the major achievement of an outstanding career – the first rail bridge over the Queensferry Narrows.

Bouch’s Tay Bridge

Bouch’s Tay Bridge

It was mid-evening of Sunday the 28th of December 1879, and a violent gale was in progress along the east coast of Scotland. Watchers at the River Tay were aware of a train confidently moving onto the bridge spans, and about seven fifteen pm, they saw a long comet of light, sweeping down to the waters. Around the same time, the Bouch family were comfortably relaxed in the glow of a family festive season gathering, at their home in Edinburgh’s West End. The strong winds, though audible, gave no cause for concern, indeed the sound served to underline the cosiness of their own particular circumstance. Mr Bouch retired to bed in due course, but was aroused in the early hours by delivery of a telegram, and I quote, “TERRIBLE ACCIDENT ON BRIDGE STOP ONE OR MORE OF HIGH GIRDERS BLOWN DOWN STOP AM NOT SURE OF THE SAFETY OF THE LAST DOWN EDINBURGH TRAIN STOP WILL ADVISE FURTHER AS SOON AS CAN BE OBTAINED.”

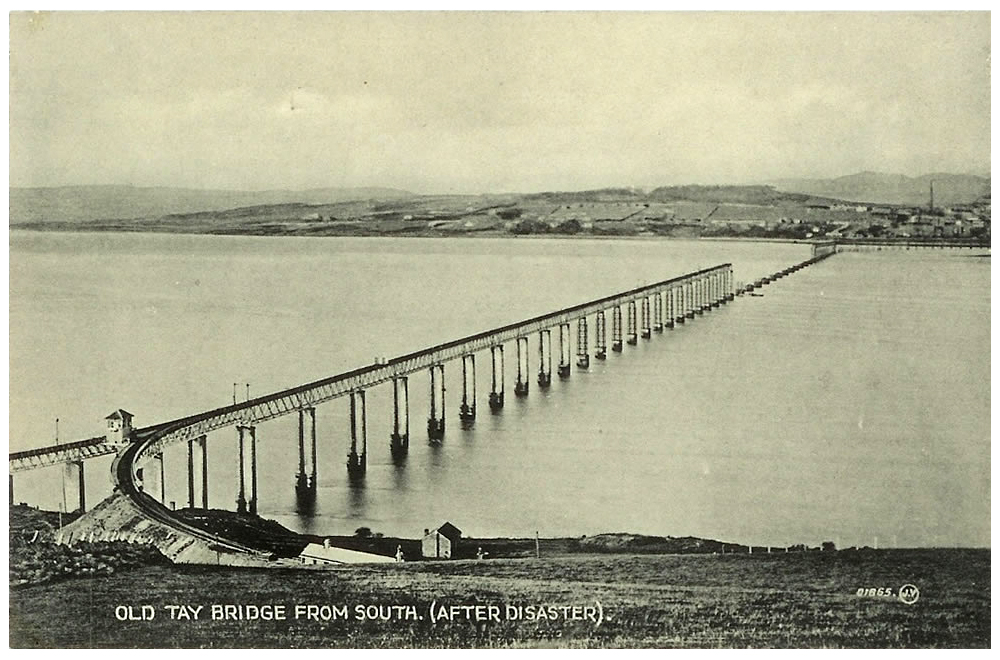

Bouch’s Tay Bridge after the disaster

Bouch’s Tay Bridge after the disaster

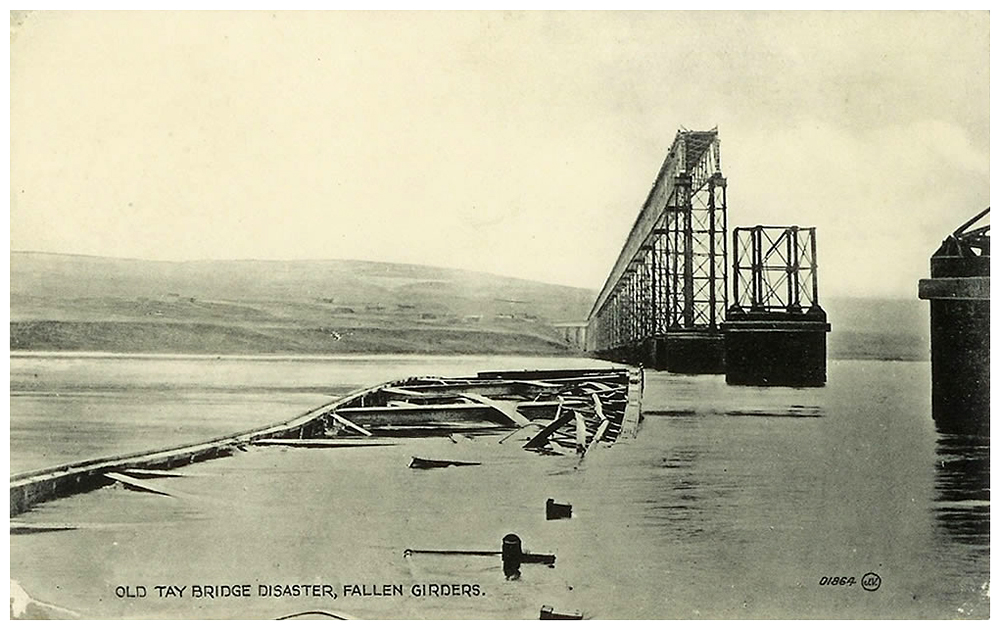

Dawn revealed a scene of devastation. Thirteen high spans had been blown down, bodily displaced by high winds. The comet of light reported by watchers was the Edinburgh down train tumbling into the waters below. An estimated seventy-five persons lost their lives. A fitting epitaph to that monument of discarded piers still upstanding in the waters of the Tay, might well be, “so many died, when one man erred.”

Girders from the high spans.

Girders from the high spans.

Sir Thomas was a broken man, totally discredited at a subsequent committee of inquiry, which disclosed gross underestimations of loading, and inadequacies of manufacture and inspection. Since the shortcomings only became evident after his designs for the Forth Suspension Bridge had been accepted, and indeed whilst construction was under way, it is within the bounds of probability that a like disaster would have overtaken the Bouch structure planned for the Queenferry passage.

Sir Thomas withdrew from the engineering scene, and became a recluse at his home in Moffat, Dumfriesshire. He was in a persistent state of acute melancholia, and died on 1st of November 1880, less than a year after the structural and personal disaster.

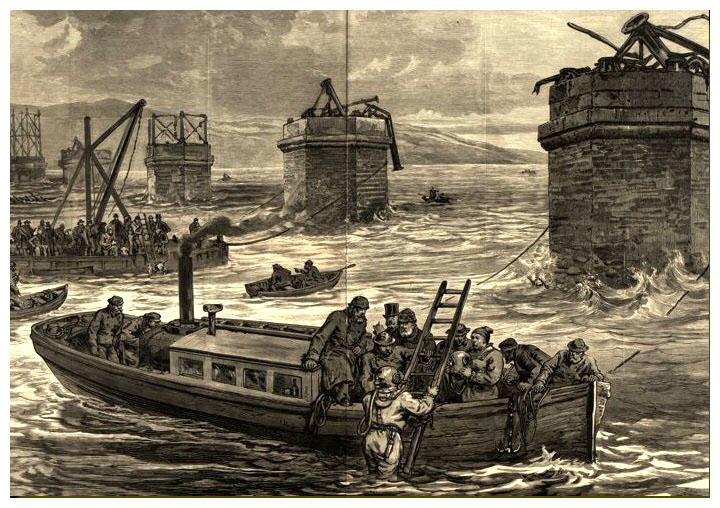

Recovery work in progress

Recovery work in progress

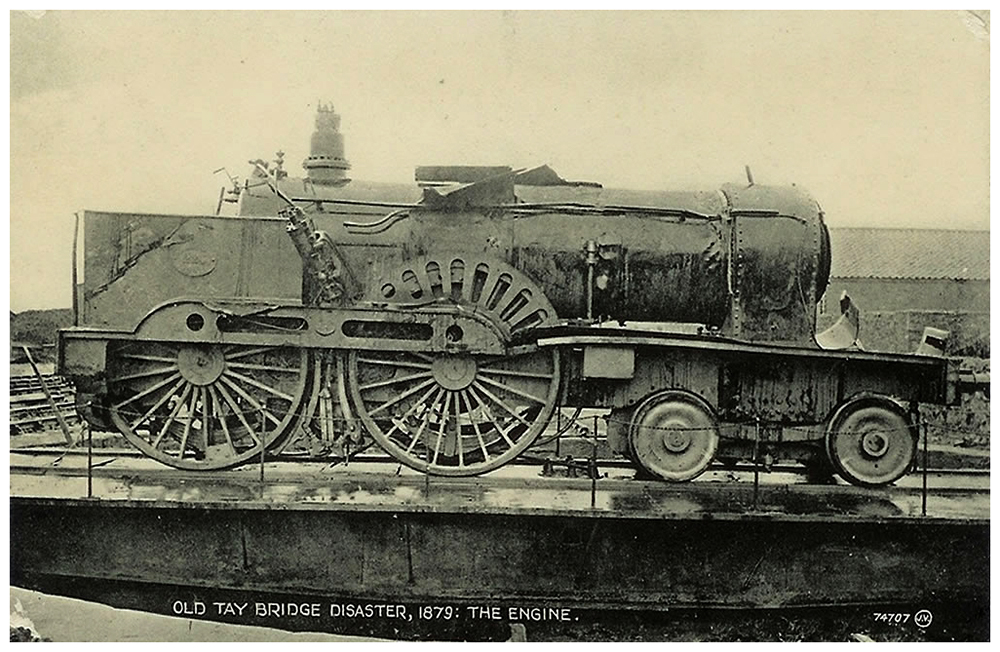

The engine from the fateful train was recovered and returned to service – nicknamed “The Diver”

The engine from the fateful train was recovered and returned to service – nicknamed “The Diver”

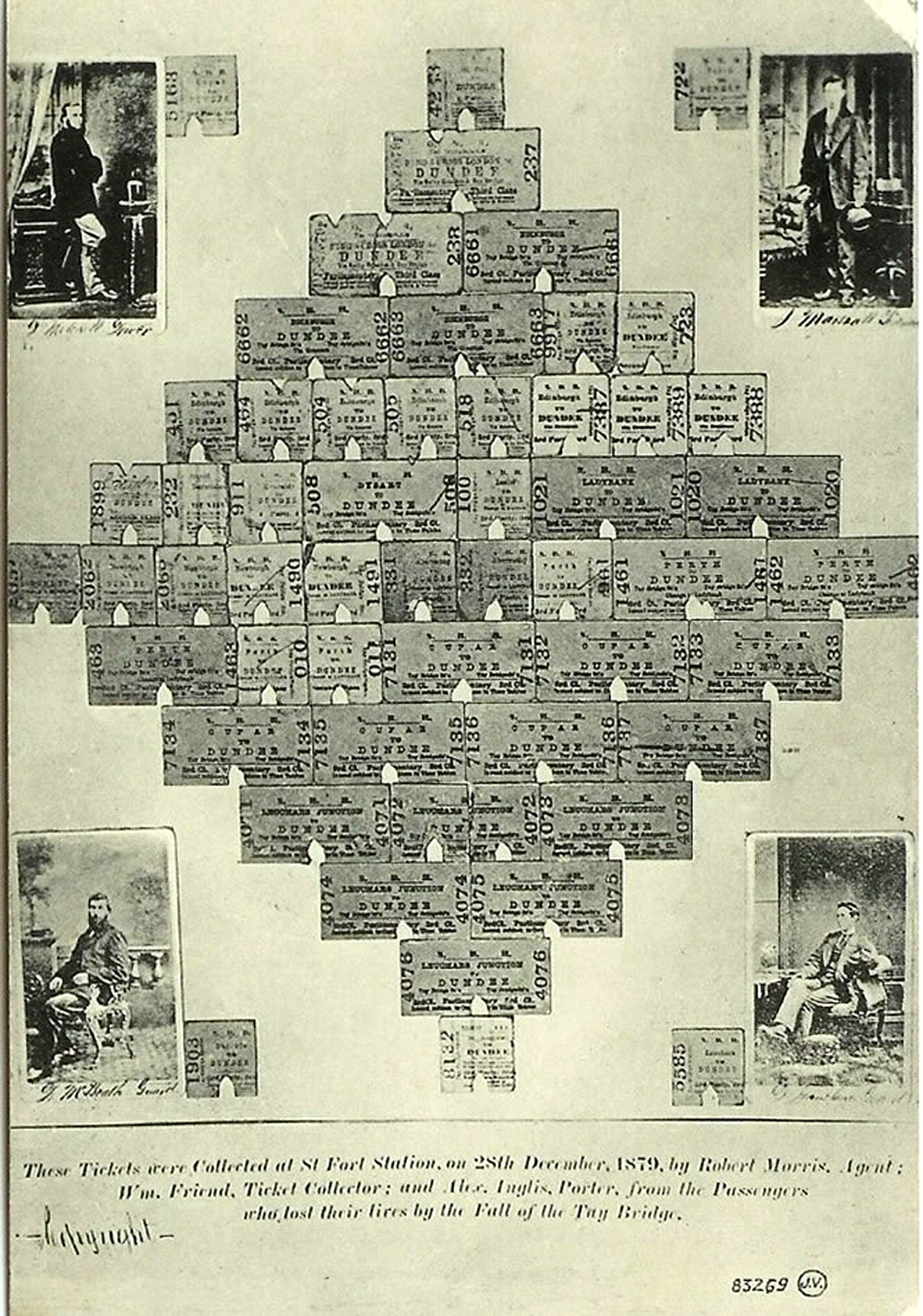

Tickets collected from passengers at the last station before the crossing

Tickets collected from passengers at the last station before the crossing

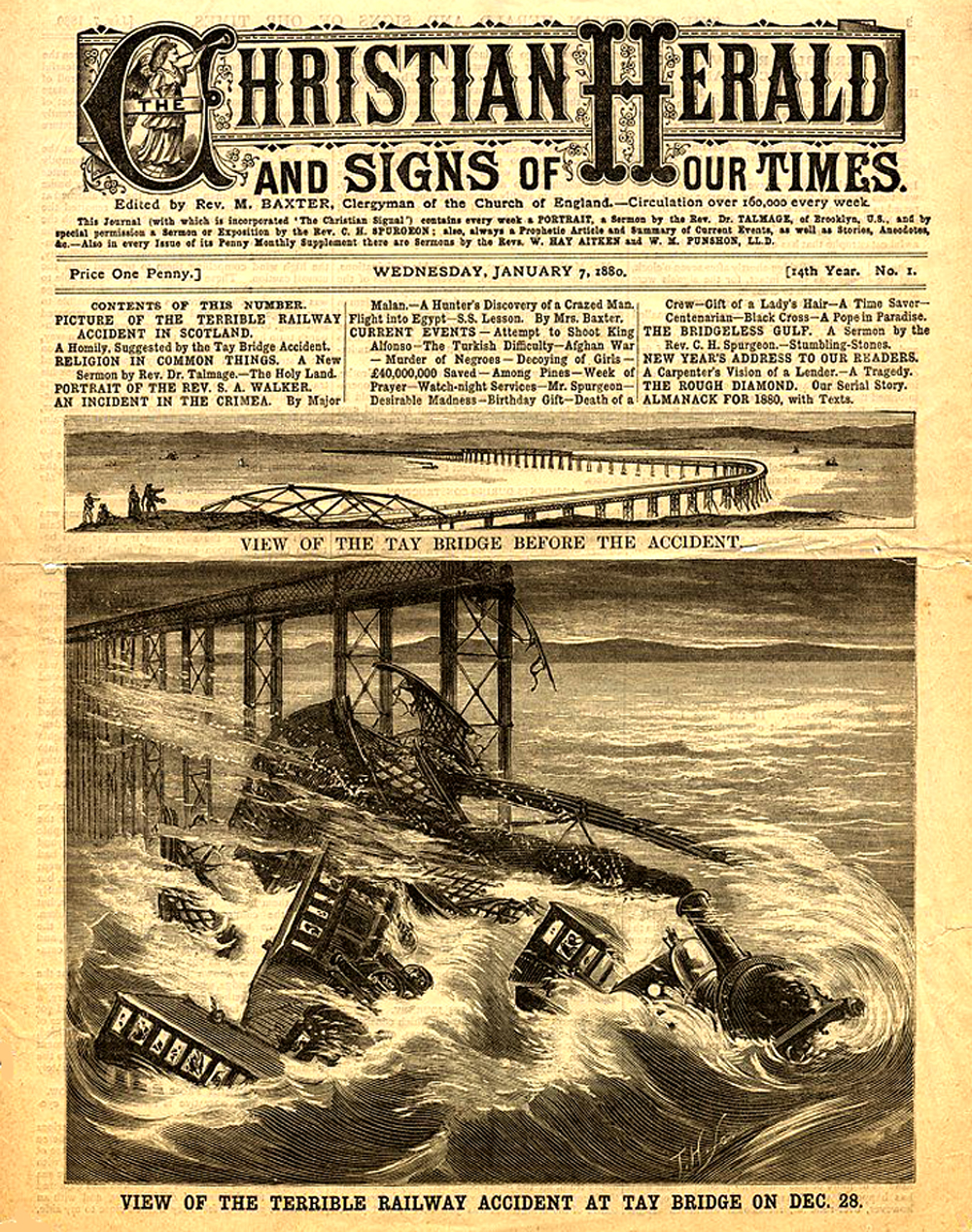

The disaster as reported by the Christian Herald

The disaster as reported by the Christian Herald

The disaster as reported by the Christian Herald

THE TAY BRIDGE DISASTER

Some account of this dreadful accident will be found on page 17, but we may here add that up to Wednesday night no more bodies had been recovered, although one of the divers reported that he had felt what he believed to be the clothing or some persons in the submerged carriages. On Wednesday, at a meeting held at the Town Hall, Dundee, under the presidency of the Provost, it was stated that the number of lives lost was certainly not less than seventy five, many of the victims being young men and women who were the stay and support of their aged parents, whilst some had left widows and large families of young children. It was resolved to establish a Relief Fund, to be administered by a Committee, including: the Provost and other local officials, and it was announced that subscriptions to the amount of £1,830 had already been promised, including £500 from the North British Railway Company, besides individual sums from directors to the amount of £560. Sir T. Bouch himself contributing £250. On the same day the directors held a meeting, at which it was decided that immediate steps should be taken to re-establish communication by way of the bridge.

Local opinion seems to attribute the accident to the extreme narrow-ness of the bridge (only fifteen feet), and confidence is expressed that one twice the width, with a double line or rails would be perfectly safe. It is also thought that the extreme height of the centre girders is not really necessary for the passage of such vessels as ordinarily frequent the river.

Our engravings of the Bridge from the Firth, and from the Tay side, are reproduced from The Graphic of Oct. 27th, 1877; that representing the official visit to the ruins is from a sketch, and the sectional view of the girders from a photograph, both kindly sent to us by Mr. James Russell of Dundee; while the view of the Bridge from the Fife bank is from a sketch by Mr G.M. Paterson of Dundee.

What caused the disaster

In 1889 the report of a Board of Trade inquiry was published. It blamed a faulty design and poor workmanship.

More than a century later, engineers and managers are still seeking lessons.

Here are two reports from 1997 and 2002 respectively

Engineering Dreams Into Disaster – History of the Tay Bridge 1997

Forensic engineering – a reappraisal of The Tay Bridge Disaster 2002

| < Bouch’s Forth Bridge | Δ The Queensferry Passage | The Forth Bridge > |