Light Tower History

| < Intro | Δ Index | Early Lighthouse Lights > |

Today, the crossing is dominated by three mighty bridges, but for hundreds of years travellers relied on the services of the boatmen who lived in the villages of North and South Queensferry. They could cross with their small boats when the tides and weather were suitable. They would cross when they felt like it! Embarking and disembarking involved a hazardous scramble over wet slippery rocks.

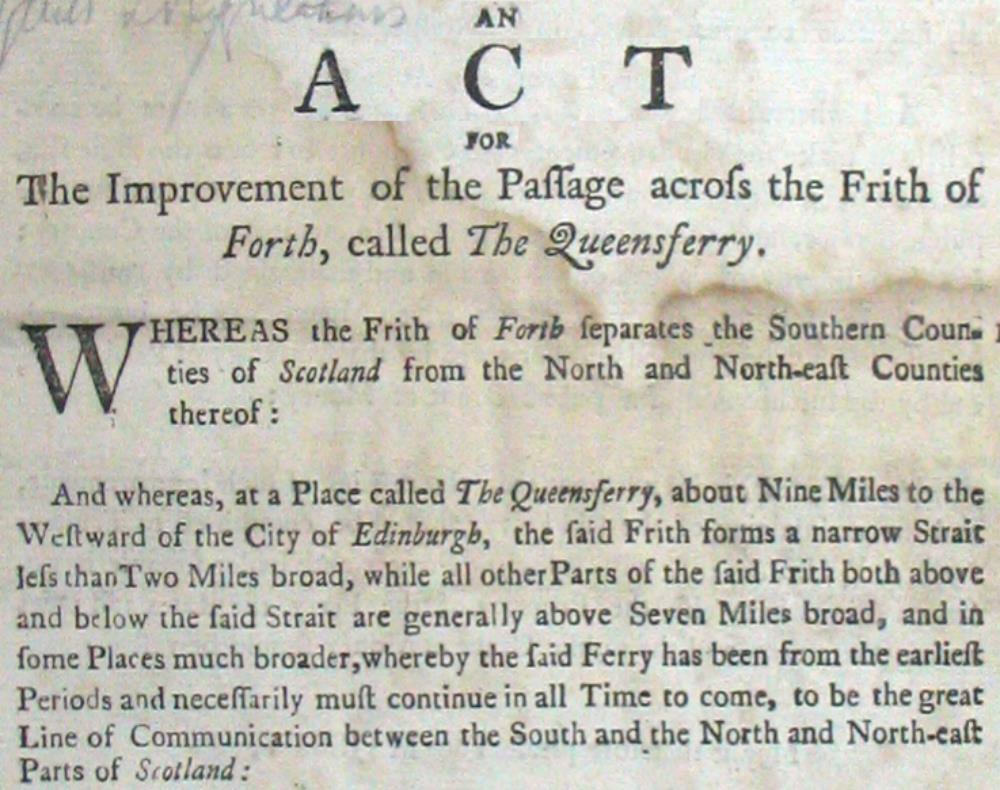

Some two hundred years ago, this state of affairs was deemed to be unacceptable by the government of the day, so in May 1809 they passed an Act of Parliament calling for major improvements to the Passage:

“Whereas the Frith of Forth separates the Southern Counties of Scotland from the North and North-east Counties thereof:

And whereas, at a place called The Queensferry, about Nine Miles to the Westward of the City of Edinburgh, the said Firth forma a narrow Strait less than Two Miles broad, while other parts of the said Firth, both above and below the said Strait are generally above seven ,miles broad, and in some places broader, whereby the said ferry has been from the earliest Periods, and necessarily must continue in all Time to come, to be the great line of communication between the South and the North and North-east parts of Scotland:”

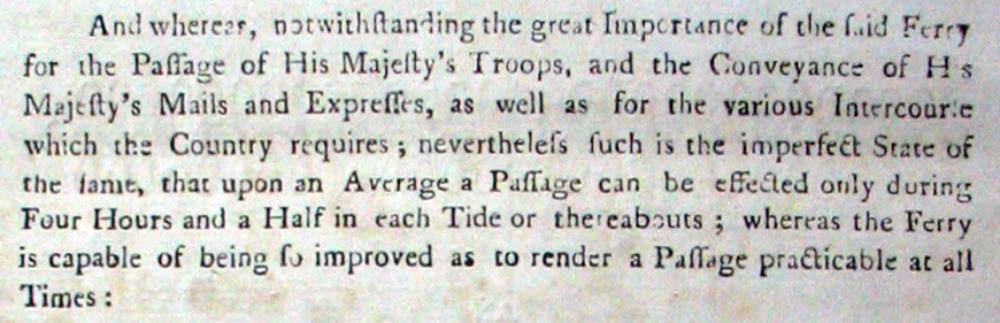

“And whereas, notwithstanding the great Importance of the said Ferry for the Passage of His Majesty’s Troops, and the Conveyance of His Majesty’s Mails and Expresses, as well as for the various Intercourse which the Country requires; nevertheless such is the imperfect state of the same, that upon an Average a Passage can be effected only during Four Hours and a Half in each Tide of thereabouts; whereas the Ferry is capable of being so improved as to render a Passage practicable at all Times:”

The Act went on to create a Public–Private Partnership, to own the infrastructure and improve conditions on the passage. The total cost of improvements was estimated to be £16,500. Half of this sum would be granted by government, and half was to be raised by the Trustees of the Passage. The trustees would raise capital by selling shares, with dividends to be paid from the revenue generated by fees on the passage.

The Trustees were the local great and good

The Lord Advocate

The Lord Justice Clerk

The Lord Chief Baron

The Commander of the Forces N.B.

The Commander of Ships in the Forth

The Earl of Rosebery

The Earl of Hopetoun

The Lord Provost of Edinburgh

John James Hope Esq of Craigie Hall

The Earl of Elgin

The Earl of Moray

Sir Charles Halkett Bart.

Admiral Sir Philip Durham

Sir David Moncreiff Bart.

Lord Abercrombie

Sir Peter Murray Bart.

The Act spelled out how the new company would operate.

The crossing was to be tightly regulated:

No more than two thirds of boats were to be at either side at any time

Boats were to sail when signalled, there was to be no unnecessary waiting for passengers or freight

No officer was to sell beer, ale or spirits.

Boatmen could not be pressed into the Navy, provided no more than 37 men and 13 boys were employed.

The operation of the ferry was to be run by a Management committee, an Engineer, Surveyor, Treasurer, Collector, Receiver, a Clerk, and two resident Superintendents.

They had compulsory purchase powers which covered the existing infrastructure of Piers, Buildings, Ferry Boats, and also specific parcels of land on which to build new infrastructure.

The improvements to be made were spelled out in detail.

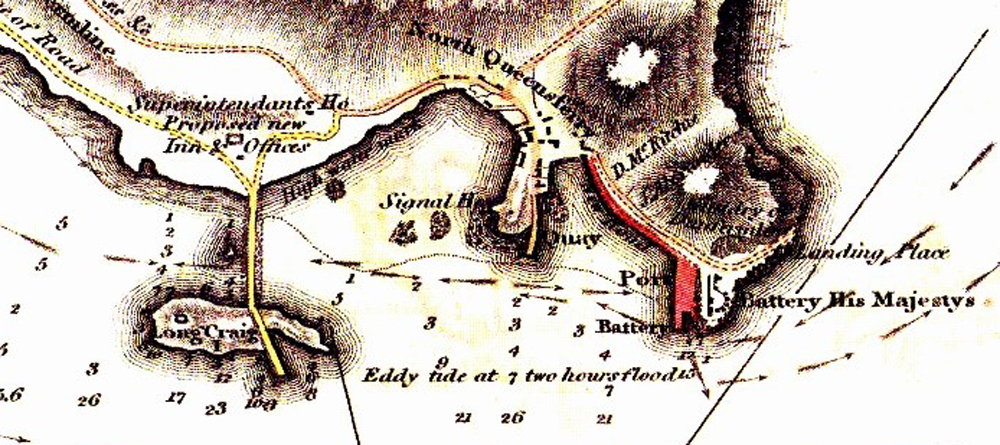

At South Queensferry, there were to be new piers at Longcraig, and Port Edgar, and improvements to the existing Hawes Pier. A new road would link these piers and storage sheds, stables, and housing for boatmen would be constructed.

At North Queensferry, the existing East Battery Pier was to be improved, with, new piers at West Battery (Town Pier) and Long Craig Island. There were to be houses for boatmen, a house for superintendent, an inn and a building to house offices and a waiting room.

The construction project was placed in the hands of three giants of 19th century civil engineering: John Rennie, Thomas Telford and Robert Stevenson.

John Rennie had amassed considerable experience in building docks and bridges. In a brilliant career he designed three world famous bridges: Waterloo Bridge, Southwark Bridge and the new London Bridge. John Rennie drew up the master plan for the “improvements.” A line of four piers at South Queensferry would be mirrored by three at North Queensferry. This arrangement would allow sailing boats to cross in either direction without tacking; regardless of wind and tide. The advance of technology in the form of steam ships removed some of the need for these piers; only two were built at North Queensferry – Battery Pier and the Town Pier. Sailing and rowing boats were retained for many years, because steamships could not operate safely after sunset.

John Rennie had amassed considerable experience in building docks and bridges. In a brilliant career he designed three world famous bridges: Waterloo Bridge, Southwark Bridge and the new London Bridge. John Rennie drew up the master plan for the “improvements.” A line of four piers at South Queensferry would be mirrored by three at North Queensferry. This arrangement would allow sailing boats to cross in either direction without tacking; regardless of wind and tide. The advance of technology in the form of steam ships removed some of the need for these piers; only two were built at North Queensferry – Battery Pier and the Town Pier. Sailing and rowing boats were retained for many years, because steamships could not operate safely after sunset.

Rennie’s master plan for the Queensferry Passage

Rennie’s master plan for the Queensferry Passage

Mount Hooly – opposite the Light tower

Mount Hooly – opposite the Light tower

In North Queensferry, Rennie also designed this rather splendid building – Mount Hooly – to house the waiting room on the ground floor, and offices on the upper floor. It will feature shortly in the story of the light.

Thomas Telford surveyed and built the road linking London and Holyhead and was responsible for the Menai Bridge He built hundreds of miles of roads and canals throughout Britain and was instrumental in opening up the Highlands to join the trade routes to the south.

Thomas Telford surveyed and built the road linking London and Holyhead and was responsible for the Menai Bridge He built hundreds of miles of roads and canals throughout Britain and was instrumental in opening up the Highlands to join the trade routes to the south.

Between 1803 and1820 he built over 920 miles of roads and no less than 1200 bridges in the Scottish Highlands but his supreme work was the construction of the Caledonian Canal linking the North Sea with the Atlantic Ocean.

Telford became the first President of the Institution of Civil engineers and was largely responsible for establishing Civil Engineering as a profession. He died aged 77 and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

In North Queensferry, his main contribution was from 1828 to 1834, when he extended the Town Pier to allow for the increasing use of steamboats (first introduced in 1821) that required a longer pier.

This 20th century photograph shows ferries operating from the extended Town Pier, and to the right, the Railway Pier

This 20th century photograph shows ferries operating from the extended Town Pier, and to the right, the Railway Pier

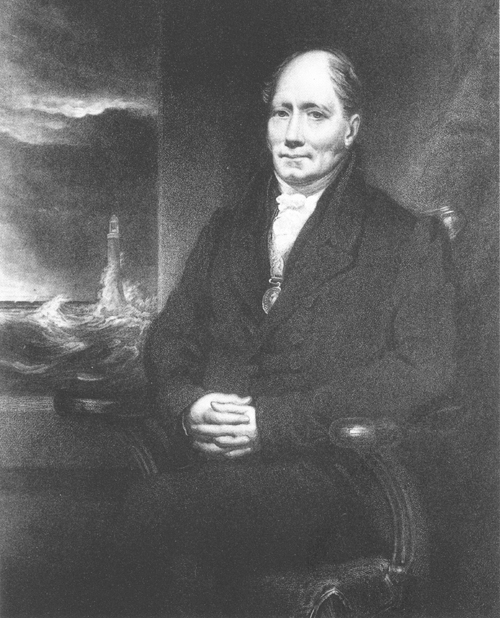

Robert Stevenson was the founder of the famous engineering family, and grandfather to Edinburgh-born writer Robert Louis Stevenson. He was consultant to the Northern Lighthouse Board for 34 years from 1808 to 1842. He designed and supervised the construction of 18 major lighthouses around Scotland and the Isle of Man. The completion of the Bell Rock Lighthouse in 1811 was considered to be his greatest achievement where he collaborated with John Rennie.

Robert Stevenson was the founder of the famous engineering family, and grandfather to Edinburgh-born writer Robert Louis Stevenson. He was consultant to the Northern Lighthouse Board for 34 years from 1808 to 1842. He designed and supervised the construction of 18 major lighthouses around Scotland and the Isle of Man. The completion of the Bell Rock Lighthouse in 1811 was considered to be his greatest achievement where he collaborated with John Rennie.

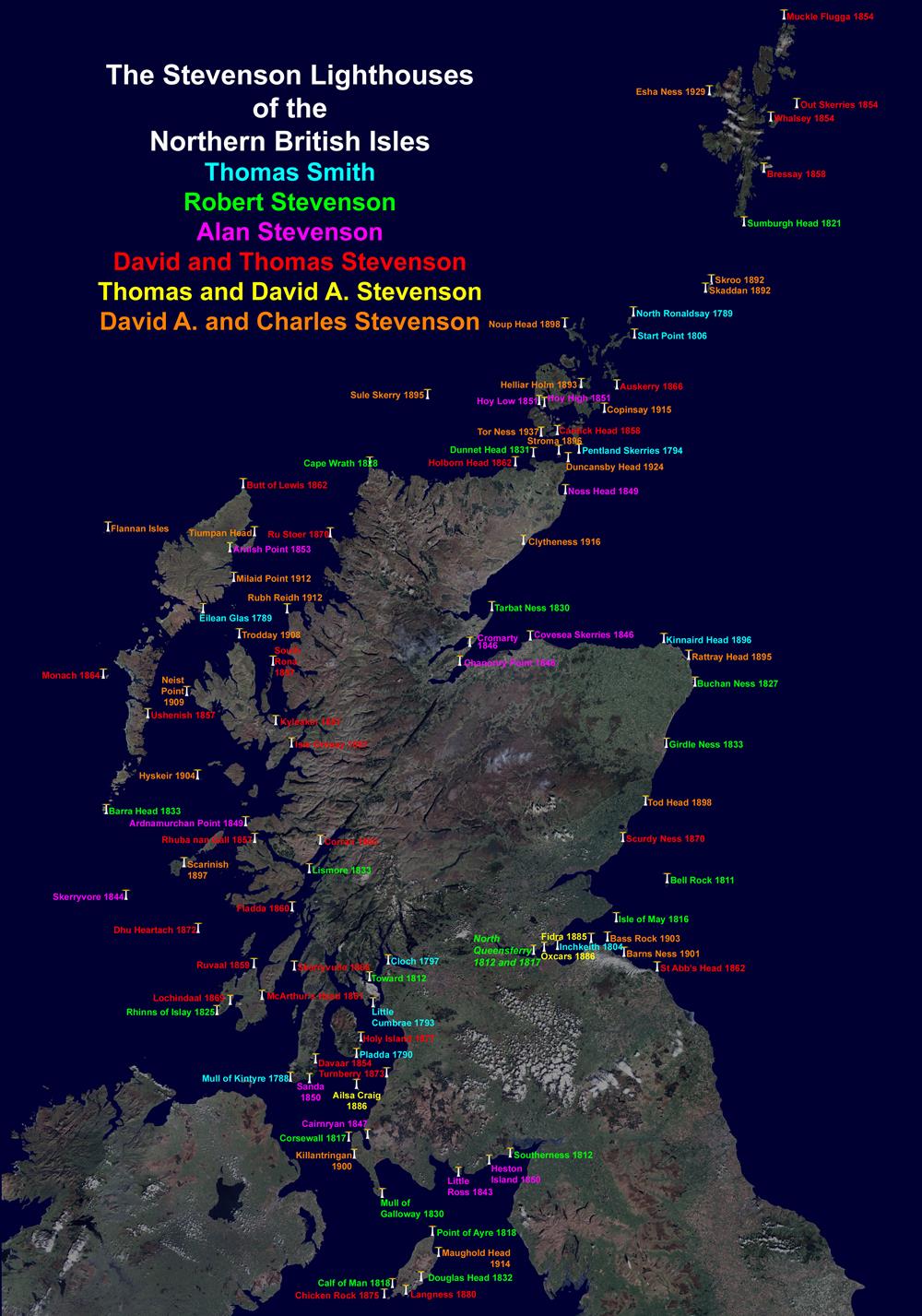

The Stevenson Family lighthouse legacy began with Robert’s stepfather, Robert Smith – of whom more later – and continued through five generations of Stevensons.

This diagram shows the lighthouses they built round Northern Britain, but their legacy extended to India, Asia, New Zealand and Japan.

In 1812 he was approached by the Trustees of the Queensferry Passage, to determine where best to place a light at North Queensferry. His suggestion was to build a light room on top of the existing external staircase on the Ferry Offices and Waiting Room – Mount Hooly. The trustees went along with Stevenson’s recommendation, and the light was duly installed on Signal House. It probably looked something like this:

By 1817, it was realized that the light was not in the optimum location to guide ferries and to cast light along the Town Pier, so a new Light tower as built and the light room transferred to the top of the new tower.

A sharp-eyed observer will note that while the stone tower is hexagonal, the light-room is octagonal.

This is probably because the light-room is octagonal, because the staircase tower on Mount Hooly where the light room was originally installed is octagonal.

However most light towers are hexagonal – including the sister light on the Hawes Pier at South Queensferry – with hexagonal light rooms.

Here is a copy and transcript of Stevenson Reports from 1817 discussing the transfer of the light from Mount Hooly to the Light Tower.

| < Intro | Δ Index | Early Lighthouse Lights > |