August 1914 – War

| < Back to Dundee | Δ Index | Military Aviation during WWI > |

The Aeroplane August 5th 1914 – War!

At this moment of writing it appears that this country is inevitably committed to take its part in the greatest war the world has ever seen. Thanks to the machinations of politicians who pose as statesmen the Powers find themselves grouped quite in the wrong way. Our alliance with France is as it should be, but that the two leading civilised nations should find themselves allied with Russia against Germany and Austria, is altogether unnatural. Servia thoroughly deserves all the thrashing she gets. The .Serb is an unlovely and unlovable beast, and has been so as long as history recalls, and it is utterly foolish that we should be called upon to waste men and money over what is Servia’s fault. The alliance with Russia is against all reason. “Scratch a Russian and you find a Tartar,” is an ancient proverb. Scratch a Tartar and you find a Chinaman is its logical sequel. The Slav is the real “Yellow Peril,” for the Slav is at bottom an Asiatic. Our alliance with Japan was an equally unnatural contract, but it was good diplomacy, for without it the Russo-Japanese war would never have taken place, and Russia would have been stronger than she is to-day. But for that war our Indian frontier would have been in greater danger than it is. If Russia comes out on top in this present war, does anyone think that her gratitude to us for our support will cause her to keep her hands off India when she can spare men from her German frontier? Those who know the Russo-Indian problem will remember the admonition of the old shikarri in Mr. Kipling’s famous allegory —”Make not your peace with Adamzad, the bear that walks like a man.”

However, nothing on God’s Earth can excuse Germany’s unprovoked attack on France, and we have got to see France through her trouble on that account. Quite probably, by the time these notes appear, an equally unprovoked attack will have been made on our own fleet, for already the Germans are holding up our merchantmen in German ports. A smashed Germany is not as good a bulwark against the advance of the Slav peoples as a solid Germany backed by France and Italy would be, but perhaps a smashed Germany may be less dangerous than a top-heavy Germany ready to fall at any moment on us and our friends the French. Therefore, in the name of common sense let us have at it, and smash Germany thoroughly, once and for all.

Germany is built up of many incompatible elements, the Schleswiger is a Dane, and quite a good chap. The Alsatian is a Frenchman and hates Germany. The Bavarian is a peace-loving, hard-working, decent poor soui), and cordially dislikes his Prussian master. And the Pole is nothing in particular, and loathes German, Russian, and .Austrian with beautiful impartiality. The German Empire dissolved into its component parts may still be a useful barrier, and not a danger. It is Prussia, as usual, who is making a beast of herself, and it is Prussia rather than Germany whom we have to fight. Of course, our cause is an unjust one, but that makes no difference. To quote the cynic’s verse:-

“Thrice armed is he who hath his quarrel just,

But more so he who gets his blow in fust.”

If those who misgovern us have any sense left, our First Fleet should by now have bottled up the mouth of the Kiel Canal. If it has not been done then the German Fleet is now loose in the North Sea, and our food supplies are not as secure as they ought to be. As Napoleon said, “The Lord is on the side of the big battalions,” and our immediate duty is to see that the French Army is augmented by our whole Expeditionary Force. It only amounts to the strength of about one Army Corps of any Continental Power, but it is splendidly organised and equipped, and should account for more than its weight of any other army. With it will go the Military Wing of the Royal Flying Corps, which, considering its small size, is probably the most efficient force of its kind in the world.

The Equipment of the R.F.C.

Since Brigadier-General Sir David Henderson has had a free hand with the R.F.C. enormous strides have been made with its equipment, but he has not been able to accomplish the impossible. The smallness of the R.F.C. is due primarily to the obstinacy of the previous controllers of the War Office who did their best to discourage the production of aircraft—despite the efforts of Colonel Capper, R.E.—and, secondarily, to the dog-in-the-manger policy of the Royal Aircraft Factory, who succeeded only too well in squeezing out promising firms of aeroplane makers, and in holding back the development of others. It is also entirely the fault of the R.A.F. that we have practically no British aero engines. Both aeroplanes and engines were “crabbed” in every possible way, so that their development might be delayed until the R.A.F.’s own products were nearer to being fit for use. The R.A.F. tractor biplanes, “B.E’.s” and “R.E.s,” have proved successful as flying machines—though constructionally defective — but the R.A.F. engine has been a dismal failure, consequently, we can produce aeroplanes, which can be built in a month or so, but we have hardly any engines—a position aggravated by the fact that it takes as many months to make an engine as it does weeks to make an aeroplane.

Such engines as we have are all of foreign make. There is not one British-built engine in use by the R.F.C. Even those firms who are building engines in this country to foreign design have had to obtain certain of their materials abroad. Truly, a pretty state of affairs, and one for which the R.A.F. is absolutely, solely, and entirely to blame.

The question is whether we have enough spare engines in the country to make good the wastage of war. The R.F.C. has a small stock of spare engines, but, thanks to lack of official encouragement, civilian flying is in such a bad way that there are only a few low-powered engines in the country apart from those owned by the Government.

I suggest to the War Office that its wisest course is to send out orders at once for a number of single-seater “scouts” with 50-hp Gnomes to firms like the Bristol and Sopwith Cos, and if those firms are too busy to turn the machines out now, let them sub-let the contracts to smaller firms like Blackburn, the Eastbourne Co., the Perry Co., the Hamble River, Luke and Co., and any others they can discover.

With 50-hp Gnomes these little scouts will do well over 65 m.p.h., and the engines would be far more useful in this way than if the Army bought up old school box-kites and tried to use them. Such 8o-h.p. Gnomes as are available should be commandeered and used for machines of proved value such as the 80-h.p. .Avros, Sopwiths, and Bristols. Firms like Vickers Ltd., the Grahame-White Co., Armstrong-Whitworths, and Handley Page, who are already at work on B.E.s, should be accelerated and supplied with ail the 70-h.p. Renaults out- of Maurice Farmans, and the Aircraft Manufacturing Co. should concentrate on Henri Farmans, unless their new tractor biplane is already approaching completion—when it is ready it can be accepted without question.

It is probable that quite a reasonable number of Beardmore-Daimler, Green, and Curtiss motors are nearly ready in the works, and these should be hurried forward and used for R.E.s by the R.A.F.—for perhaps in this national emergency even the staff of that institution will sink its jealousy of certain British products, and will do its best in the country’s service.

By concentrating the work of each firm on specific types large number of machines could be turned out in the next two months, and these machines would be equally valuable either for military work abroad or for coast patrols from the Naval Air Stations.

The Navy’s Affair.

The Navy is, of course, even less supplied with aircraft than is the Army, for the former Lords of the Admiralty were even more hopelessly fossilised than were the people at the War Office, and Mr. McKenna was worse than useless. Since the advent of Mr. Churchill, and the appointment of Captain Murray Sueter as Director of the Air Department, wonderful progress has been made, and, better still, every possible encouragement has been given to British firms. We are better off for seaplanes than is any other country, though that is not saying much. Happily, both Short Brothers and J. Samuel White and Co. are in a position to turn out machines at short notice, and theirs are undoubtedly the finest seaplanes in the world at present, for they can be used in quite heavy seas. The Sopwith Co. also are making excellent sea machines, and can deliver fairly promptly. The trouble here, as in the Army, is engines, though the Air Department has done its very best in the short time it has existed to encourage the British maker, but we probably have enough to go on with for a while. Neither we nor any other country have aeroplanes which can be launched with certainty from warships, but we have the advantage in that many of our seaplanes can get off rough water and so can be used with a fleet at sea, while the enemy’s cannot. The Navy has a fair number of land-going machines quite suitable for coast-patrols, and by taking its low-powered engines out of school machines and fitting them into fast scouts, this number can be considerably increased. I venture to suggest also that light two-seater seaplanes of 8o-h.p. or so, without wireless, and with small fuel capacity, can be used effectively with a fleet at sea, and that A. V. Roe and Co. could make such machines quite rapidly. Such machines would never go out of sight of the Fleet, or, at any rate, should keep company with a fast ship of the scout class, ahead of the fleet, the aeroplane being used solely for observation from a great height, and not to cover great distances. A naval observer on such a machine, piloted by a civilian volunteer perhaps, would spot hostile ships long before his own fleet was sighted, and would, at any rate, prevent surprise, thus being of defensive if not of offensive value. Such machines, carrying hand-grenades, could also be of use against a German airship accompanying a German fleet, if such an airship ventured near our ships.

Our airships are, of course, quite without value in this war, except for coast patrol work in fair weather and within a strictly limited district.

Taking it all round, our position, so far as aircraft are concerned, might be worse, and for this we must thank the energy of the Air Department at the Admiralty and the Department of Military Aeronautics. But it ought to be a great deal better, and it is to be hoped that when the war is over someone in authority will have sufficient strength of character to lay the blame where it is deserved.

Finally, on behalf of all concerned with aircraft, one wishes the officers and men of the Royal Naval Air Service, and of the Royal Flying Corps, success in the great task which lies before them, and a happy issue out of all their dangers. —

C. G. G.

Flying Prohibited

The Aeroplane – [Wed] August 5, 1914.

Prohibition.

The Home Office issued the following notice on Saturday [1st August 1914] : — In pursuance of the powers conferred on me by the Aerial Navigation Acts, 1911 and 1913, I hereby make for the purposes of the safety and defence of the Realm the following Order :—

I prohibit the navigation of aircraft of every class and description over the whole area of the United Kingdom, and over the whole of the coastline thereof and territorial waters adjacent thereto.

This Order shall not apply to naval or military aircraft, or to aircraft flying under naval or military orders; nor shall it apply to any aircraft flying within three miles of a recognised aerodrome.

(Signed) R. McKenna,

One of his Majesty’s Principal Secretaries of State.

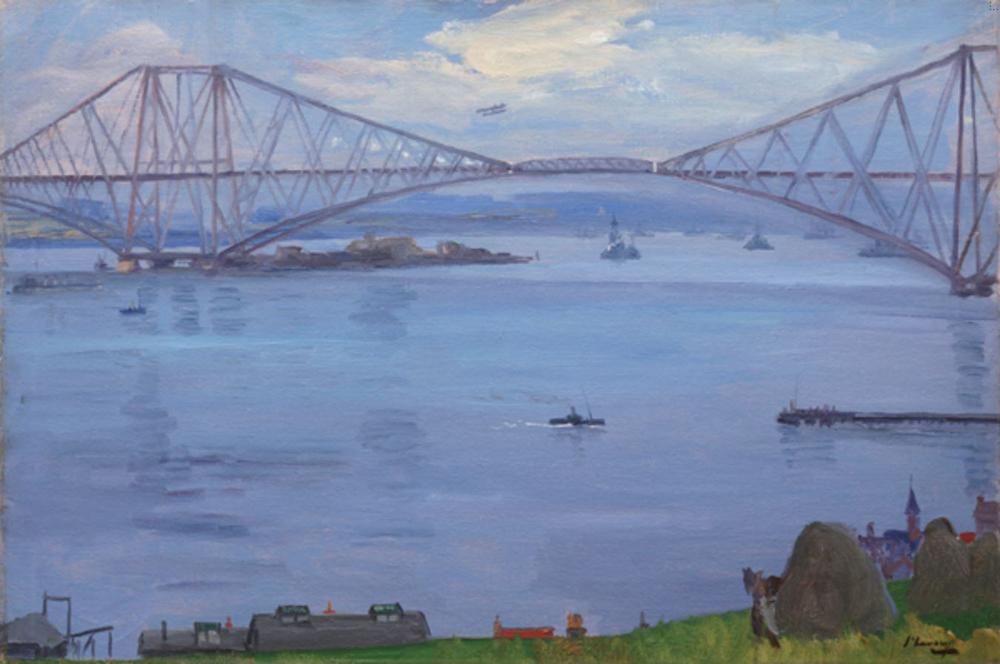

The Forth Bridge, September 1914 – Sir John Lavery

This view was probably painted in September 1914, in the knowledge that war had recently been declared and that this tranquil scene would soon be transformed.

| < Back to Dundee | Δ Index | Military Aviation during WWI > |