Secret experiments at Blair Atholl

| < The Aero Club of Great Britain | Δ Index | The Blair Atholl Aeroplane Syndicate > |

Lt. John William Dunne, son of Lt.-General Sir John Dunne, became interested in the problems of stable flight during 1900 after he was invalided home from the Boer War, in which he had served as an officer of the Wiltshire Regiment.

He experimented with paper models of a fixed-wing aeroplane of inherently stable lay-out for nearly two years until 1905 when he enlisted official support to put his ideas into full-size form.

At that time, Dunne’s official position was that of a designer H.M. Balloon Factory, South Farnborough, where Col. J. E. Capper allowed Dunne to start construction of his first aeroplane. Security measures were stringent from the outset. The work was carried out in complete secrecy behind locked doors, and Dunne himself was not allowed to wear his uniform, being shown in the Army List as an invalided officer on half-pay. A condition of War Office assistance was that he should be paid half a guinea a day “when actually at work”.

Dunne’s automatically-stable lay-out was vee-shaped swept-back wing biplane, in which the tips were washed-out at negative incidence to ensure maximum stability. The D.1, as it was named, was constructed first as a glider, the intention being to fit engine power once the general design had demonstrated its feasibility.

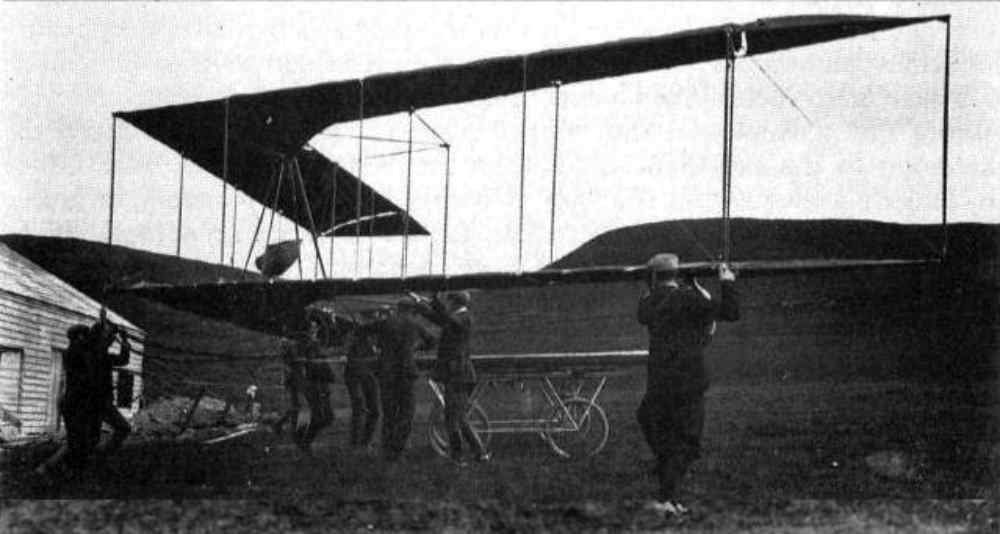

The inherently stable Dunne D1A glider at Blair Atholl in the Scottish highlands being manhandled onto the launching trolley (being prepared for flight at Glen Tilt in 1907).

The inherently stable Dunne D1A glider at Blair Atholl in the Scottish highlands being manhandled onto the launching trolley (being prepared for flight at Glen Tilt in 1907).

(For the technically minded. . . Wash-out means that the wing is twisted slightly along its length, with the root of the wing having more up-tilt than the tip. Negative incidence means that tip of the wing is twisted below the horizontal.

When the root (inboard section) of a wing flies at a higher angle-of-attack, it means the root will reach the critical angle-of-attack sooner than the tip, so it will stall first.

If the wing stalls at the root first, it means there’s enough airflow over the tips of the wings to prevent any rapid rolling motion during a stall, which makes the airplane more stable. It also makes the plane more resistant to entering a spin.

If a wing didn’t have washout, it would mean the entire wing would stall at once, or worse, the wing tip could stall first causing the plane to roll aggressively possibly enter a spin.)

The project had the support of R. B. Haldane, the Secretary of War, who to ensure that the flying tests also were conducted in secret requested the Marquis of Tullibardine, the heir to the Duke of Atholl, to allow the use of his estate among the mountains at Blair Atholl in Perthshire, Scotland, for the purpose.

The Marquis agreed, and a wooden shed was built on a lonely grouse moor at Glen Tilt to house the aircraft, which was taken there and assembled by a small party of men in plain clothes, consisting of Lt. Dunne, Lt. Westland, three other officers, two N.C.O.s of the Royal Engineers and a few servants.

In addition to the aircraft shed, eight tents were set up a mile away to house the men in a self-contained camp.

In spite of the measures taken to prevent news of the work becoming public, something of what was being done leaked out, and Glen Tilt was besieged by newspaper reporters and German spies, the Duke of Atholl’s private army of gillies being kept busy warding off the intruders.

In order to conceal the details of the machine as much as possible from prying eyes, the subterfuge of camouflage was resorted to. This was applied by painting chordwise thin white stripes and irregular outlines across the dark upper surfaces of the wings.

Tests of the glider were conducted in 1907 by Col. J. E. Capper, the Superintendent of the Balloon Factory, as Dunne’s health made it unwise for him to attempt to fly it. Repairs were necessary following a crash into a wall during a brief flight, and the machine was next fitted with a pair of Buchet engines whose total combined output was 15 h.p., but although the War Office contended that 15 h.p. was sufficient for the use of the Army, the D.1 was under-powered and failed completely to take-off.

The undercarriage consisted of skids on both the glider and the powered D.1, and a four-wheeled platform was employed finally to get the D.1 to fly by launching it down an inclined plankway built a few feet above the ground level. When the carriage was started down the track the rubber-tyred wheels climbed the curb fitted to the edge of the plankway, and it fell over the side, carrying the aeroplane with it. The D.1 was damaged too badly for it to be repaired in time for any further experiments before the winter snows were expected.

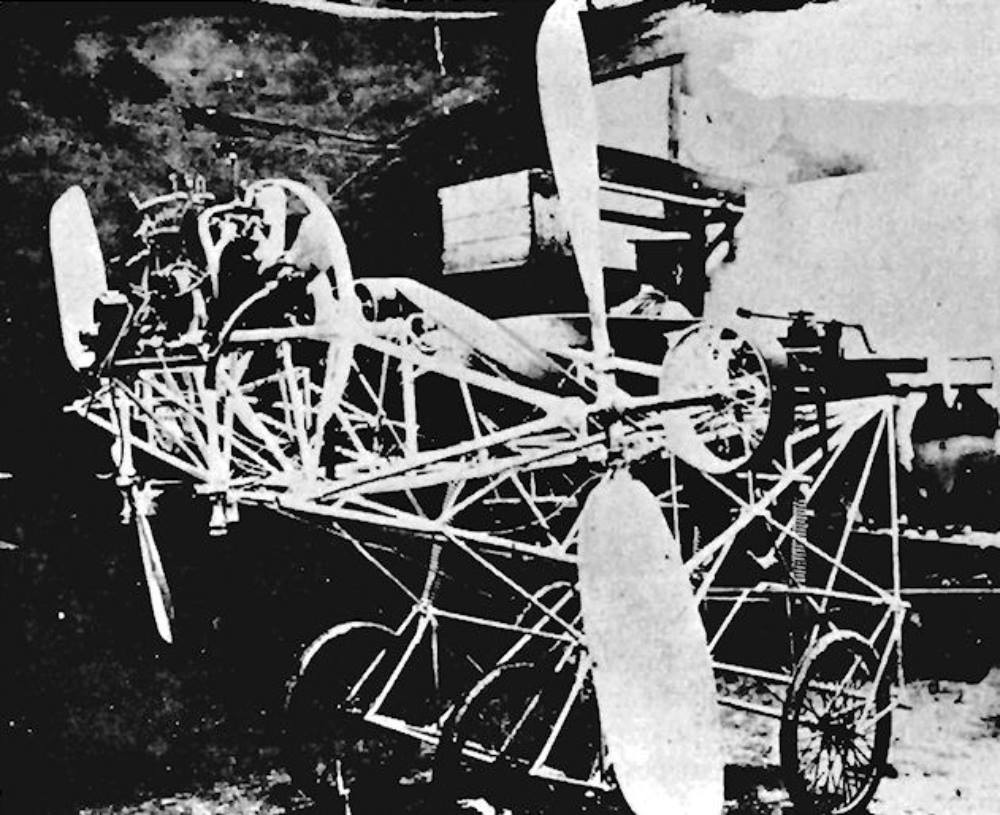

By mid-1908, the D.1 had been rebuilt and at the same time modified in an attempt to make a success of it. Redesignated D.4 it was now a more practical machine fitted with a 25 h.p. R.E.P. engine driving a pair of propellers by crossed flat belts over drums, and an enclosed nacelle for the pilot which was embodied on the underside of the lower wings’ centre-section. Below this there was attached to the tubing chassis a sprung, four-wheeled undercarriage in place of the original skids.

Dunne D.2 – The D.2 designation was given to a small glider version of the Dunne-Huntington Triplane, which was proposed but not built.

Dunne D.3 – The D.3 was a smaller glider version of the D.4 and was built at H.M. Balloon Factory. It was fitted with a twin-skid undercarriage, launching being carried out from a four-wheeled trolley. As with the D.1 and the D.4, camouflage was applied in white stripes and linear patterns to break up the continuity of the dark upper surfaces.

The D.3 was tested during September and October, 1908, at Glen Tilt, Blair Atholl, Perthshire, by Col. J. E. Capper, who rose to about 15 ft. height sitting in it, and also by Lt. L. D. L. Gibbs, who flew the machine for a distance of 44 yds on 9th October, 1908, before crashing it a little later.

Dunne D.4

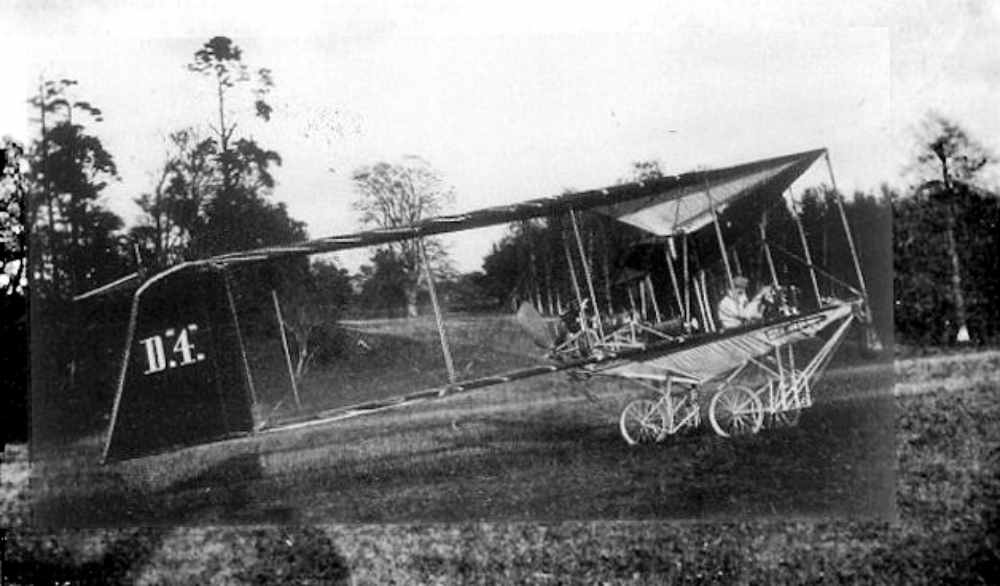

Dunne D.4 at Blair Atholl in 1908. The Dunne D4 biplane was built by mounting the D1 glider on a four-wheeled chassis which also incorporated the pilot’s position.

Dunne D.4 at Blair Atholl in 1908. The Dunne D4 biplane was built by mounting the D1 glider on a four-wheeled chassis which also incorporated the pilot’s position.

The steel tubing chassis constructed in the Army Balloon Factory during September, 1907, shown complete with 25 h.p. R.E.P., and used to convert the D.1 into the D.4.

The steel tubing chassis constructed in the Army Balloon Factory during September, 1907, shown complete with 25 h.p. R.E.P., and used to convert the D.1 into the D.4.

Vertical fins were added to the extremities of the wings. Once again, the upper surfaces were disguised with the thin white lines and designs. Lt. Lancelot D. L. Gibbs, of the Royal Field Artillery, undertook the testing of the D.4 for the War Office in the Lower Park at Blair Atholl during the autumn of 1908. The R.E.P. engine could not be persuaded to develop enough power to take the machine fully into the air, but it did manage to leave the ground on the level for short hops without an accidents occurring. Eight of these brief flights were accomplished between 16th November and 10th December 1908, a distance of 40 yds being covered on the last date.

Finally, in 1909, the War Office decided that, after spending £2,500 on the experiments without any significant results being achieved, it would have to discontinue its sponsorship of the project.

Lt. Dunne severed his connection with the Balloon Factory and the D.4 was presented to him when he left.

| < The Aero Club of Great Britain | Δ Index | The Blair Atholl Aeroplane Syndicate > |