Early Lighthouse Lights

| < Intro | Δ Index | New Technology – The Argand Lamp > |

17th Century technology

The very earliest light houses used an open fire in a metal brazier to create a warning beacon.

For example, a lighthouse operated on the Isle of May at the mouth of the firth of Forth from 1635 when King Charles 1st granted a patent to erect a beacon on the island and collect dues from shipping for its maintenance.

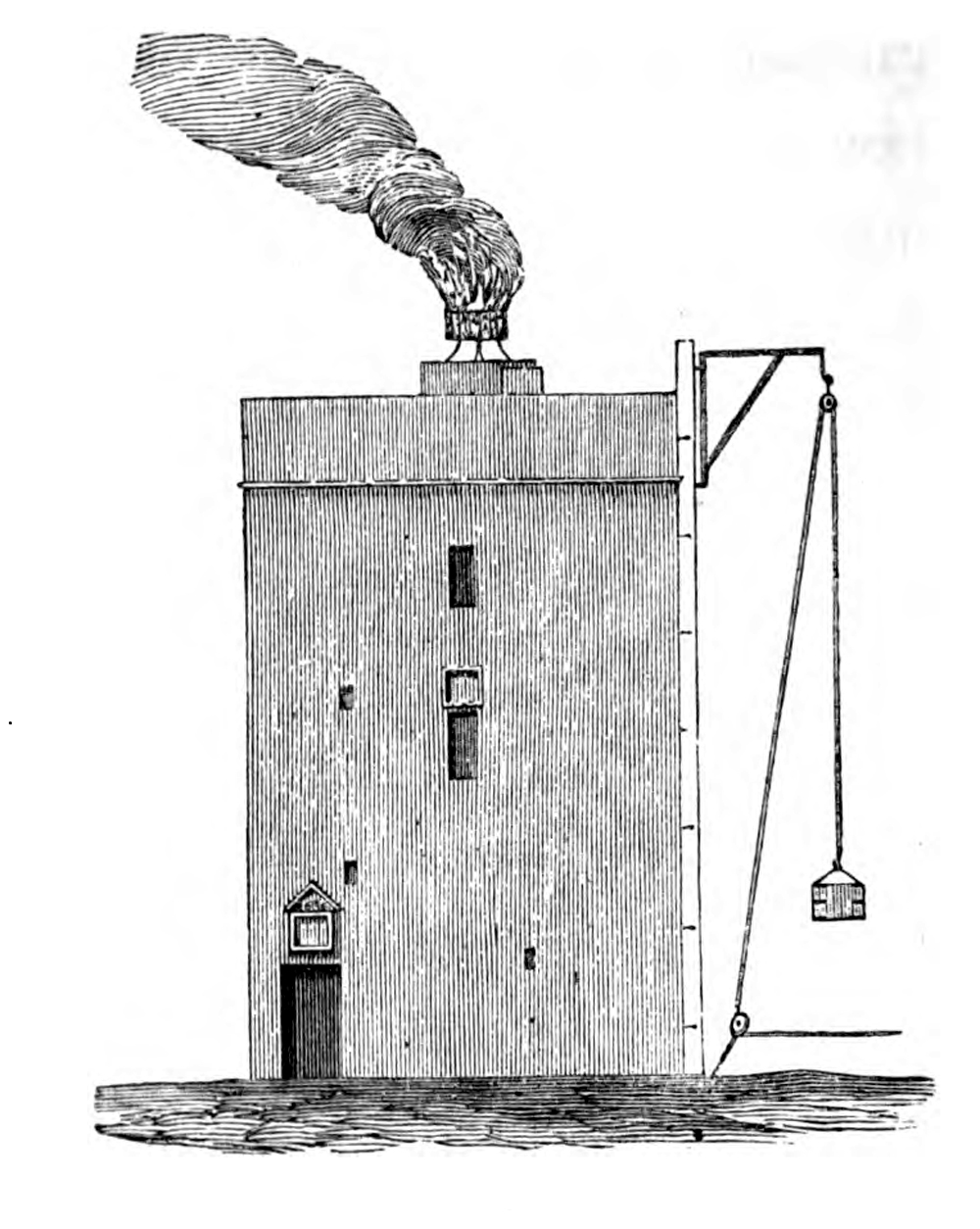

This light, however, was a crude affair consisting of a stone structure, surmounted by an iron chauffeur in which there burned a coal fire. The coals were hoisted to the fire by means of a box and pulley and three men were employed the whole year round attending to the fire which consumed about 400 tons of coal a year.

The Isle of May light from David Stevenson “Lighthouses” p70

The Isle of May light from David Stevenson “Lighthouses” p70

In 1790 a light-keepers’ entire family was suffocated by fumes, except for an infant daughter, who was found alive 3 days later.

Despite the fact that the light was regarded in its time as one of the finest in existence, its value as an aid to navigation, judged by today’s standards, must have been decidedly limited. The character of the light would vary considerably with almost every change in weather conditions. One minute it might be belching forth great volumes of smoke and the next blazing up in clear high flames, while changes in wind directions would alter its appearance. An easterly wind would have the effect of blowing the flames away from the sea so that the light could scarcely be seen where it was most wanted.

An instance of this occurred on the night of 19 December 1810 when H.M. Ships NYMPHE and PALLAS were wrecked near Dunbar because the light of a lime kiln on the coast had been mistaken for the navigation light on the Isle of May.

Lighthouse lamp requirements

So the basic specification for our light might have been: The light must be visible from two miles away (across the Forth). It must run unattended for eighteen hours (a Scottish winter’s night.) The light should have a steady output.

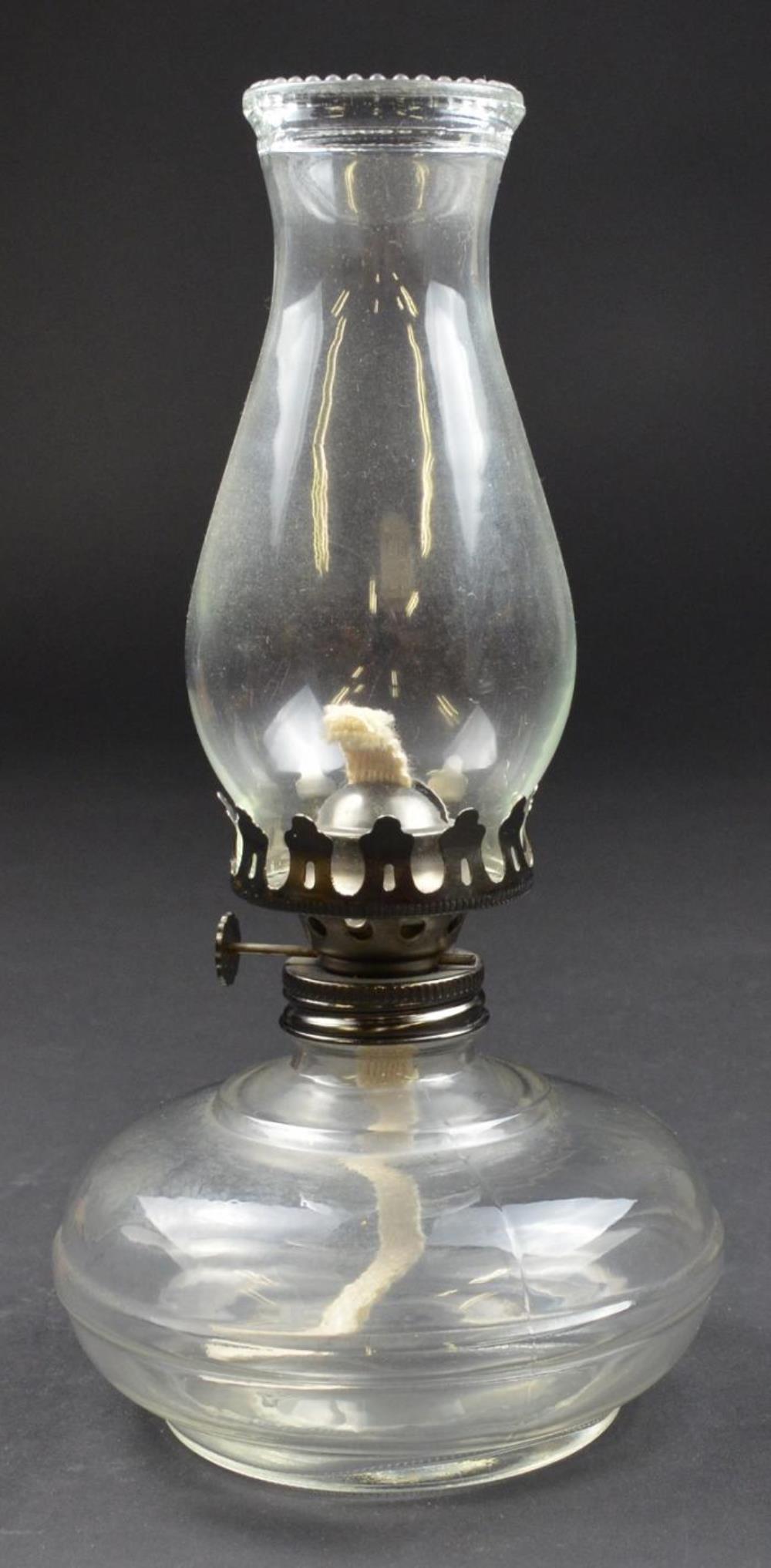

Prior to 1780, the only indoor sources of light were candles, or open oil lamps. There was no gas, electricity or mineral oil (paraffin or kerosene). Paraffin was not discovered until 1850.

Candles were used in some light houses, but they needed to be changed as they burned down. Domestic candles were made from bees-wax, which was expensive, or tallow which was cheap but smelly!

Oil Lamps

Oil lamps have been around since Roman times.

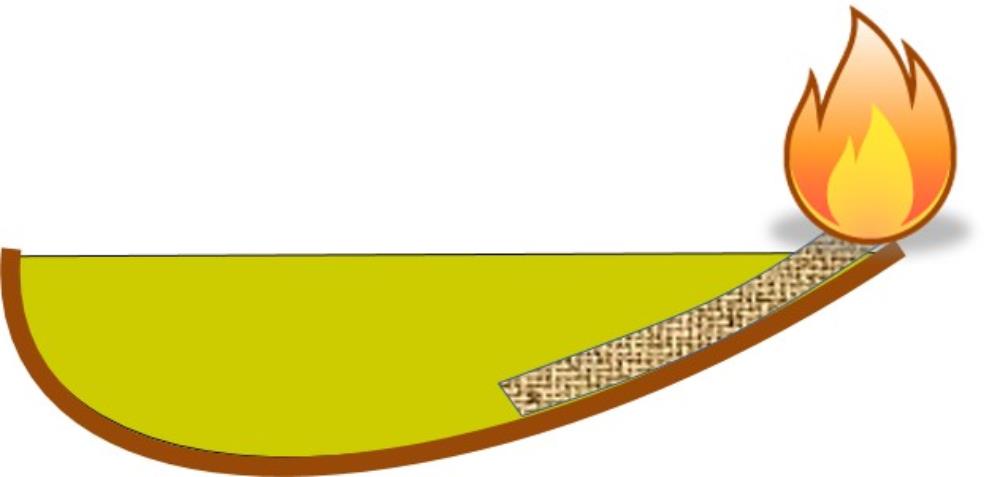

They used a shallow dish with a sloping wick in a spout.

By the late 18th century the domestic oil lamp had evolved little since Roman times.

Roman lamps probably burned olive oil, but the lamps in most Scottish houses would have burned fish-oil, and would have been even more smelly than tallow candles!

These were called “Cruzie Lamps” from an old French word meaning crucible (which lives on in the “Le Creuset” brand of cookware.)

A cruzie lamp was made from cast iron, and incorporated two new features. The oil dish could be tilted fore and aft, to adjust the level of oil at the wick and hence the height of the flame; and beneath the oil dish was a drip tray. That was the end result of 2,000 years of progress!

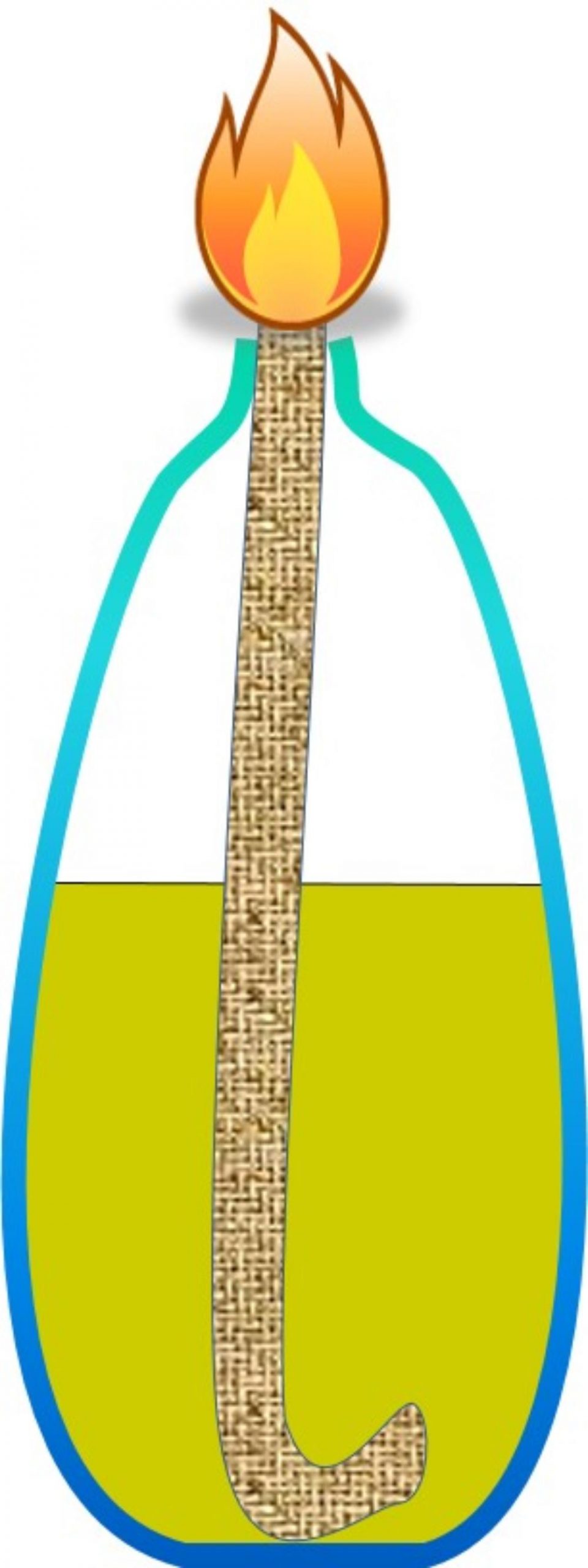

So why did these lamps look so different to our modern notion of an oil lamp? It is all to do with the properties of the oil – the combination of surface tension and viscosity.

So why did these lamps look so different to our modern notion of an oil lamp? It is all to do with the properties of the oil – the combination of surface tension and viscosity.

Here are three containers with wicks, but filled to the same level with different liquids. From left to right: water (coloured with some ink), paraffin (kerosene in the USA!), and rapeseed oil. The water wets the wick and quickly travels some distance up the wick. The paraffin shoots up the wick to the top. The rapeseed oil creeps up very slowly.

That is why a vegetable oil lamp is shallow, the oil never has to travel very far up the wick.

The lamp on the left will work with vegetable oil, but not the lamp on the right, the oil would never reach to top of the wick. It is the poor wicking quality of 19th century oils that dictate the shape of the oil lamp. The top of the wick must be very close to the level of the oil. A shallow container means that the oil level only drops slightly as it is used up. A paraffin lamp can be tall and slim, because the top of the wick can be some distance from the level of the paraffin.

1786 The First Light House Oil Lamp

Robert Stevenson’s stepfather – Robert Smith – set up a lamp business in Edinburgh some time in the 1780’s. He successfully tendered for the business of providing street lighting in the Old Town of Edinburgh in 1785.

In 1786, he became the first Lighting Engineer to the newly-established Northern Lighthouse Board.

One of Robert Smith’s adoptions was the parabolic reflector, which concentrated the light form a flame into a beam, rather than letting it spread in all directions.

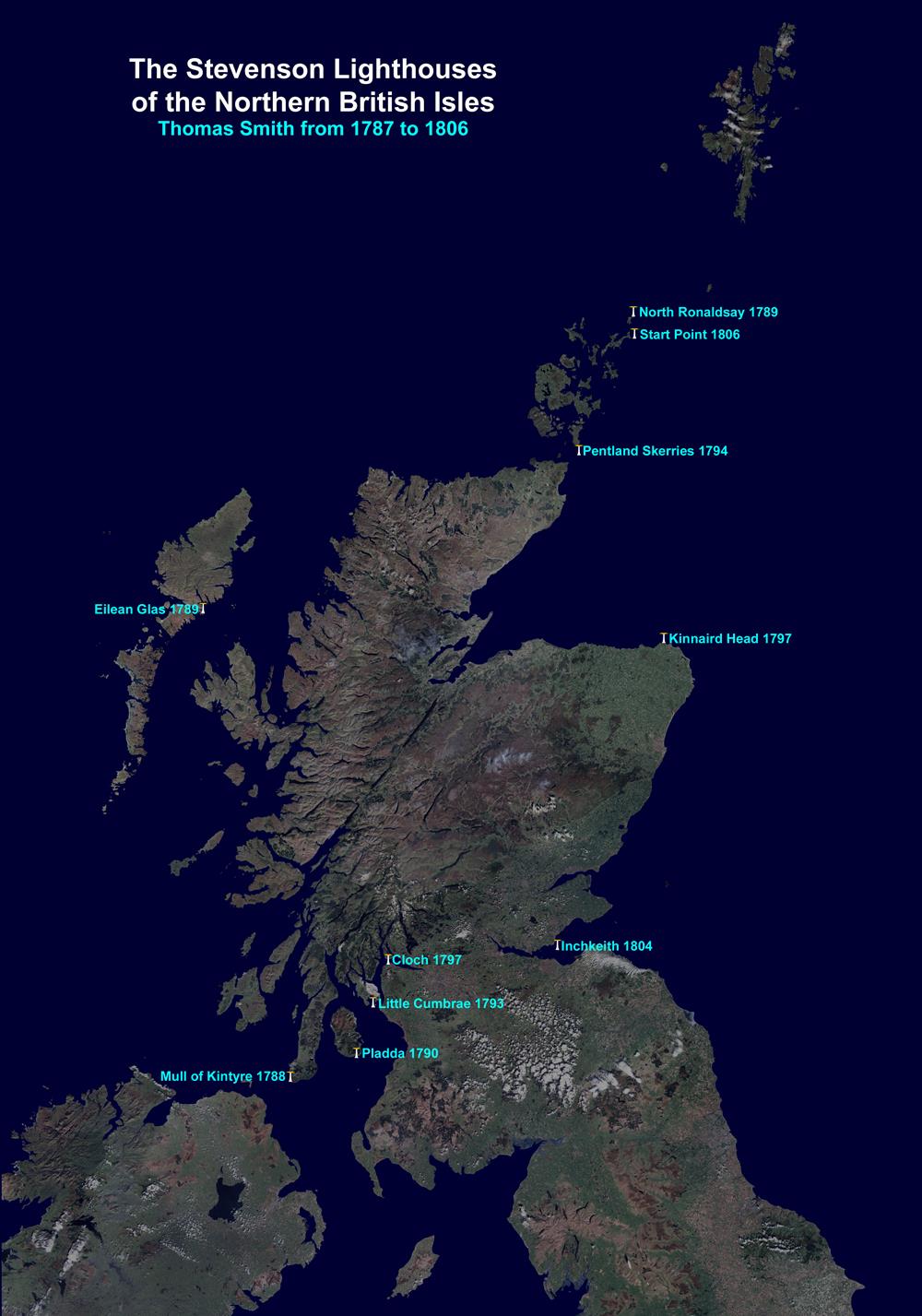

This image shows one of his early designs. The reflector is made up of small mirrored glass facets set in a ceramic dish. If you look closely you will see the familiar shallow dish of an oil lamp. The bowl protrudes behind the reflector to form a wide, shallow reservoir. Smith installed lamps like this in the eight lighthouses which he built between 1787 and 1800 (latterly with Robert Stevenson)

This image shows one of his early designs. The reflector is made up of small mirrored glass facets set in a ceramic dish. If you look closely you will see the familiar shallow dish of an oil lamp. The bowl protrudes behind the reflector to form a wide, shallow reservoir. Smith installed lamps like this in the eight lighthouses which he built between 1787 and 1800 (latterly with Robert Stevenson)

1787 Kinnaird Head

1788 Mull of Kintyre

1789 North Ronaldsay

1789 Eilean Glas (Scalpay)

1790 Pladda

1793 Little Cumbrae

1794 Pentland Skerries

1797 Cloch

1804 Inchkeith

By 1804 when the Inchkeith lighthouse was built, there had been a change in lighting technology. Ami Argand had invented a new oil lamp.

| < Intro | Δ Index | New Technology – The Argand Lamp > |