Military Aviation in Britain pre 1909

| < European aviation | Δ Index | The Aero Club of Great Britain > |

In 1784, Vincenzo Lunardi, made the first balloon flight in Britain, and in 1785 Jean Pierre Blanchard and Dr. John Jeffries flew in a hydrogen balloon from Dover to Calais

Lunardi’s balloon in flight

Lunardi’s balloon in flight

On 5 October 1785, a large and excited crowd filled the grounds of George Heriot’s School in Edinburgh to see Lunardi’s first Scottish hydrogen-filled balloon take off. The 46-mile flight over the Firth of Forth ended at Coaltown of Callange in the parish of Ceres, Fife.

The site near Pitscottie is marked with this plaque.

The site near Pitscottie is marked with this plaque.

Having seen the success of balloons in Britain and airships in France and Germany, the British government pressed ahead with their own airship design for the British Army – “Nulli Secundous” (Second to None). This was developed at the official School of Ballooning, commanded by Lt Col John Capper R.E.

Nulli Secundous had one flight, in October 1907, before being destroyed in a storm whilst anchored.

Nulli Secundous had one flight, in October 1907, before being destroyed in a storm whilst anchored.

The government was apparently not interested in aeroplanes. In the War Office Air Estimates for 1903/4 aeronautical expenditure was £14,600, just enough to run the Royal Engineers’ balloon and kiting establishment – now renamed as The Balloon factory.

But behind the scenes it was a different story. Capper not only supervised the British Army’s ballooning and airship activities, but also supervised the man-lifting “war kites” developed by Samuel Franklin Cody and the early work on aeroplanes by both Cody and J. W. Dunne.

Samuel Cody, an American showman, had engaged by the Army to make man-carrying observation kites. By 1903, his box kites could lift an observer 1,500ft off the ground. He went on to explore engines which might allow his kites to fly without a tether.

(Capper and Cody undertook the first successful flight of Nulli Secundus, over London in 1907.)

Lt Col Capper at the Balloon Factory seized on the report about the Wrights’ success. Capper and his wife were keen amateur balloonists and members of the recently-formed Aero Club of Great Britain. Capper got together with Patrick Alexander, another Aero Club member to find out as much as possible about the Wrights’ machine. Alexander had already been to the States and met the Wrights and arrangements were put in place for him to meet them again at the St Louis Exhibition in 1904 and report back to Capper.

Cody went on with his efforts to build an aeroplane based on his success with kites and the information he was able to acquire about the Wrights’ successes.

The Wrights were concerned about the leaking of information across the Atlantic and started, too late, to put patents in place.

In a separate venture, Lt John William Dunne of the Wiltshire Regiment had come up with an original but promising design for an aeroplane that would be so stable in the air that it would allow the pilot to concentrate on observation rather than keeping the craft airborne. His design was kept secret.

In December 1906, Patrick Alexander went again to the Wrights at Dayton but implied to them that there was no government interest in buying their flyer. The Wright’s No 3 Flyer, which boasted an upright position for the pilot and much better control, had achieved flights of over half an hour and 24 miles. However, it had been shut away in their shed and not flown for a full year and two months. With the Wrights feeling rebuffed and bitter, after all their efforts to interest governments in their invention, they decided to concentrate on approaches to governments through intermediaries. Their Flyer was destined to remain behind closed doors but it would be wrong though to think they were idle, as they carried on with refinements to the engine and propeller and through building a new two-seater version.

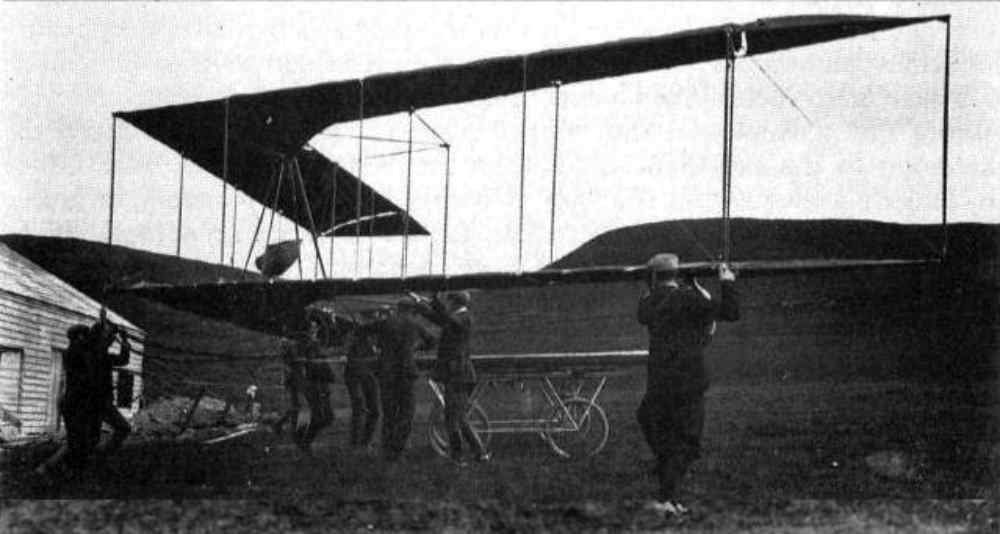

Capper oversaw the first Army aeroplanes. He briefly flew Dunne’s first glider, the D.1, during secret trials at Blair Atholl in Scotland in 1907. The flight had lasted only a few seconds when the glider crashed into a wall, with Capper sustaining a cut to the head.

Dunne’s D1 glider

Dunne’s D1 glider

1908 – First powered flight in Britain

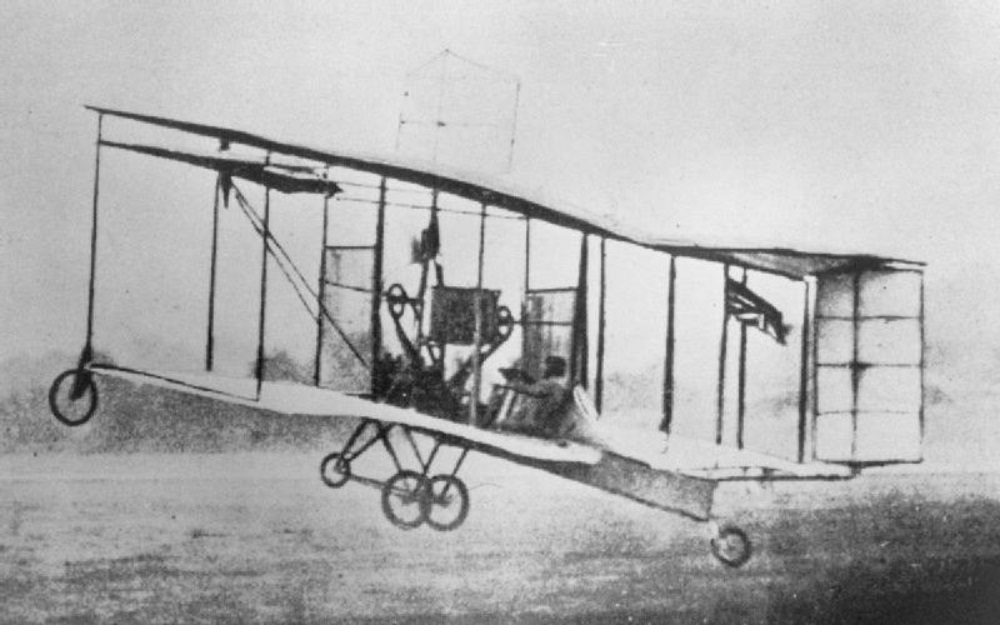

On October 16th 1908 Cody flew the first British-built aeroplane at Farnborough, which earned it the title British Army Aeroplane No.1. But being an American it did not qualify as a British record. Nor did this change the Government’s view!

First flight of British Army Aeroplane No.1

First flight of British Army Aeroplane No.1

British Army Aeroplane No.1 – after its first flight!

British Army Aeroplane No.1 – after its first flight!

In November 1907, a month after the demise of “Nulli Secundus”, work began in Germany on the construction of LZ4, a Zeppelin with a length of 446ft and a diameter of 42ft. Within seven months this airship would remain in the air for 12 hours and cover a distance of 240 miles.

Officialdom in Britain still remained wedded to the airship.

1907 – The Wright brothers try again

Orville and Wilber Wright paid more visits to Europe in 1907. They tried, to make progress with the French, they tried through the Mauser gun company to make progress with the Germans and they tried to interest the Russians. On 9th November in Paris, Wilber witnessed one of Henri Farman’s short hops. He was not impressed because the technology was, in his view, years behind what the Wrights had achieved, but he was concerned.

In 1907, the Wrights wrote again to the War Office offering full rights to manufacture their No 3 Flyer for £100,000, delivery and training thrown in. The offer was rejected. The Wrights changed their offer to the War Office to 50 aircraft at £2000 each!

The response was: “the War Office was not disposed to enter into relations with any manufacturer of aeroplanes.”

The Admiralty gave a similar response: “I have consulted my expert advisers with regard to your suggestion as to the employment of aeroplanes and I regret to have to tell you, after careful consideration of the Board, that the Admiralty, whilst thanking you for bringing the proposals to their notice, are of the opinion that they would not be of any practical use to the Naval service.”

The British view was that, if any progress was to be made with aeroplanes, then it was to be by Cody and Dunne and official evaluation of test aircraft built to their designs. As a result of the frequent visits by Patrick Alexander and others to the Wrights, there was quite a lot of information on the Wright Flyer.

Government Ignores Aeroplanes And Sticks To Airships

In Government circles the sub-committee of the Committee of Imperial Defence had been studying Aerial Navigation. The report of the committee was issued (marked secret) on 28th Jan 1909. It reported:

‘Although in the existing state of aerial navigation Great Britain is not exposed to any serious danger by land, it would be improvident and possibly dangerous to assume that the rapid developments which the art of aerostatics has recently made may not entail, in the future, risks by land or sea.

Invasion of Great Britain in air ships on a large scale may be dismissed as unlikely for many years to come…

The Committee recommended… a sum of £35,000 in the Naval Estimates for a rigid airship and…£10,000 in the Army estimates for continued experiments on navigable balloons and…the experiments at military ballooning establishments with aeroplanes should be discontinued…..but advantage should be taken of private enterprise in this form of aviation.’

Asquith’s government proceeded to put the recommendations into effect. So, at the beginning of 1909, the Wrights had astounded the world with their fully controllable practical aeroplane, the Germans were spending £400,000 per annum on aviation, whilst Britain had a Government building one rigid airship for the Navy and spending £35,000 on Army dirigibles; nothing for aircraft development.

Capt Dunne became a civilian designer. Cody was able to carry on his experiments in private as the Army gave him his aeroplane.

The frustration of informed people, both the press and the services, grew throughout 1909 born of the feeling of vulnerability and that other countries were way ahead of Britain.

It was clear that the Government was relying on, and the public at large were depending on, private enterprise in the form of the Aero Club of Great Britain.

| < European aviation | Δ Index | The Aero Club of Great Britain > |