Octave Chanute – The godfather of aviation

| < The inception of aviation | Δ Index | The Wright Brothers > |

Born in Paris, Octave Chanute emigrated to the USA in 1838 at the age of six.

In 1883, he retired from a successful career as a US railway civil engineer, and devoted his leisure time to the study of aviation. He published his findings in a series of articles in from 1891 to 1893, which were then re-published in the influential book Progress in Flying Machines.

In 1894, he began conducting his own experiments, starting with Lilienthal-type gliders.

Chanute testing a Lilienthal type glider, 1894

Chanute testing a Lilienthal type glider, 1894

In 1895, he started designing and building his own gliders.

Development of the biplane

Chanute tackled the problem of building large, light wings, by drawing on his knowledge of bridge construction, and stacking several wings together. This technique provided the necessary surface area, without having long wings which were either light but floppy, or stiff but heavy.

Over the next few years, Chanute designed and built a series of gliders with up to six tiers of wings. Augustus M. Herring, a civil and mechanical engineer, and William Avery piloted the flights and assisted Chanute.

By 1896, they settled on the Chanute-Herring Biplane, a small, but robust glider that used Pratt trussing for strength. The strut-wire-braced wing structure used in this plane is still used in biplane aircraft and was the model the Wright brothers used in constructing their gliders and first airplane.

Chanute-Herring Biplane Glider

Chanute-Herring Biplane Glider

Both Herring and Chanute contributed to the design of this aircraft. Each 16-foot (4.9-meter) wing was covered with varnished silk. The pilot hung from two bars that ran down from the upper wings and passed under his arms.

Powered flight experiments

In May 1896 Smithsonian Institution Secretary Samuel Langley successfully flew an unmanned steam-powered fixed-wing model aircraft. He continued to develop steam and gasoline powered models. The success of these experiments impressed Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt enough for him to assert that “the machine has worked” and to call for the United States Navy to study the utility of Langley’s “flying machine” in March 1898.

In 1898, Herring went on to install an engine and propellers on a larger version of the Herring-Chanute glider and flew it for short distances near his home in St. Joseph, Michigan. However the two-cylinder, three-horsepower compressed air engine could operate for only 30 seconds at a time.

Meantime The U.S. Department of War made $50,000 in grants to the Smithsonian for construction of a full-scale man-carrying version of Langley’s machine. Although Langley’s internal combustion engine was powerful, the structure and control systems proved to be inadequate when Langley attempted a manned flight. On the first flight attempt, on October 7, 1903, the craft failed to fly and dropped into the Potomac River immediately after launch. On the second attempt, on December 8, the craft collapsed after launch and again fell into the river. Rescuers pulled the pilot unhurt from the water each time. Langley blamed the calamities on a problem with the launch mechanism, not the aircraft.

The real problems lay with structure and control systems. Langley made no further tests, and his experiments became the object of scorn in newspapers and the U.S. Congress.

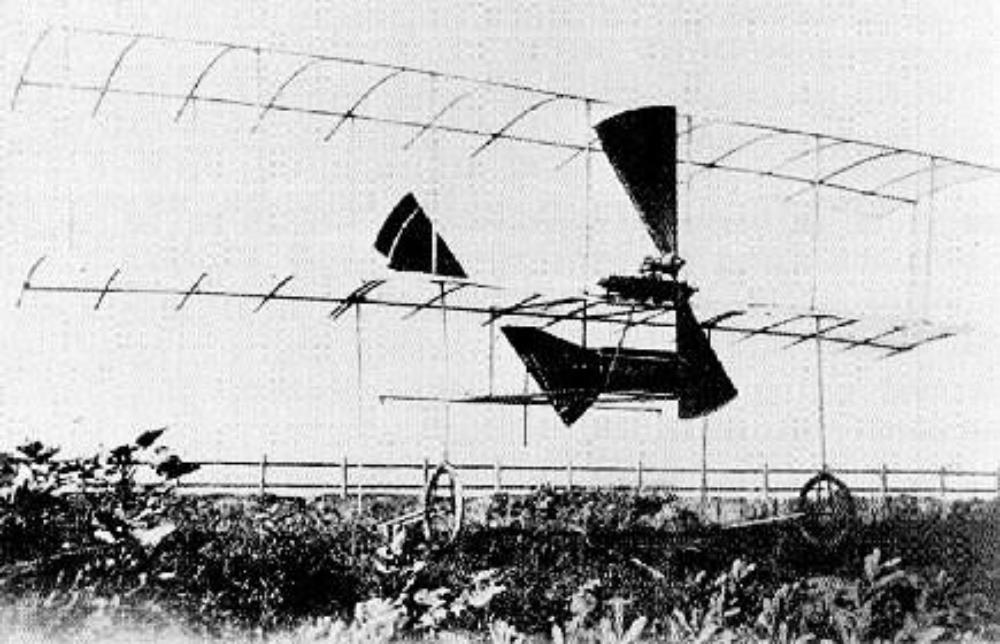

The Herring bi-motor powered glider (1898)

The Herring bi-motor powered glider (1898)

Chanute never patented his inventions and was happy to offer his findings to whoever seemed interested. He acted as a clearinghouse for ideas relating to flight, corresponding internationally with others in the field and encouraged many in their efforts – Gabriel Voisin, Louis Bleriot, Maurice Farman, and the Wright brothers.

It was the Wright brothers who solved the problem of control systems.

| < The inception of aviation | Δ Index | The Wright Brothers > |