Quarrying at the Ferry

Quarrying stone and ferrying people cattle and goods across the narrowest part of the Forth estuary was the lifeblood of the village of North Queensferry for centuries. A way of life has now gone but some of the stories live on and hopefully there is still more to be found. Ths is where North Queensferry Heritage Trust (NQHT) needs your help.

Recent research by NQHT into both quarrying and ferrying indicates that the stories unearthed so far merit additional publications. For the moment NQHT is focusing on quarrying and the ‘heritage of stone’ as it benefited the village and those who were employed whose skills we much admire today.

Stonemasonry or Stonecraft is the creation of buildings, structures and sculpture using stone as the primary material. It is one of the oldest activities and professions in human history. Many of the long-lasting ancient shelters, temples, monuments, fortifications, roads and bridges, then lighthouses – the Light Tower at the Town Pier is a good example – were built of stone.

The early history of the Forth shows the importance of the islands and why many of the buildings were constructed on the islands rather than the mainland. The Abbey on the island of Inchcolm is a good example and if you look carefully you may find a Mason’s mark as shown in this photo.

A mason’s mark on Inchcolm Abbey

A mason’s mark on Inchcolm Abbey

(A mason’s mark is an engraved symbol often found on dressed stone in buildings and other public structures.

If you find one it is well worth recording.)

For centuries North Queensferry was a close-knit community, dependent on the sea and the ferry service for its existence. However by the eighteenth century, changes were afoot. In 1763, the Guildry leased land for thirteen years to Robert Campbell, a merchant from Stirling, to quarry whinstone for road paving on the guild’s ground or rocks next to the village. The following year, he gained another lease for eight years to quarry to the east of the village and by 1767 Campbell was employing 145 men, most of whom came from nearby Inverkeithing.

In 1785, one or possibly both of these quarries was causing problems. Complaints were made about the rubbish made by small stones being transported from the guild’s quarries to the Forth and Clyde canal company. To date, the loads had amounted to 1,638 tons. Large-scale quarrying had arrived in the peninsula.

That Quarrying was becoming an important part of North Queensferry life, is clearly indicated in a report by Thomas Pennant (1726-1798), the Welsh born scientist and naturalist, published in the 1770s after his tour of Scotland:

“. . . landed in the shire of Fife, at North-Ferry, near which are the great granite quarries, which help to supply the streets of London with paving stones; many ships then waiting near to take their lading

The granite lies in great perpendicular stacks; above which is a reddish earth filled with friable micaceous nodules. The granite itself is very hard, and is all blasted with gun-powder: the cutting into shape for paving costs two shillings and eight-pence per tun, and the freight to London seven shillings.”

Today we know the ‘granite’ as dolerite, a tough coarse-grained rock shot through with crystals. One of the best known examples of the use of dolerite is the building of Stonehenge on the Salisbury Plain.

The legacy of quarrying in North Queensferry, with its 7 quarries, shows how the village and geology that surrounds it are closely related. With help of some local residents and the British Geological Survey (BGS) team in Edinburgh the NQHT plans to ‘leave no stone unturned’ to build a story of how the industry developed and what opportunities there may be in future from the only remaining quarry in the area at Cruickness.

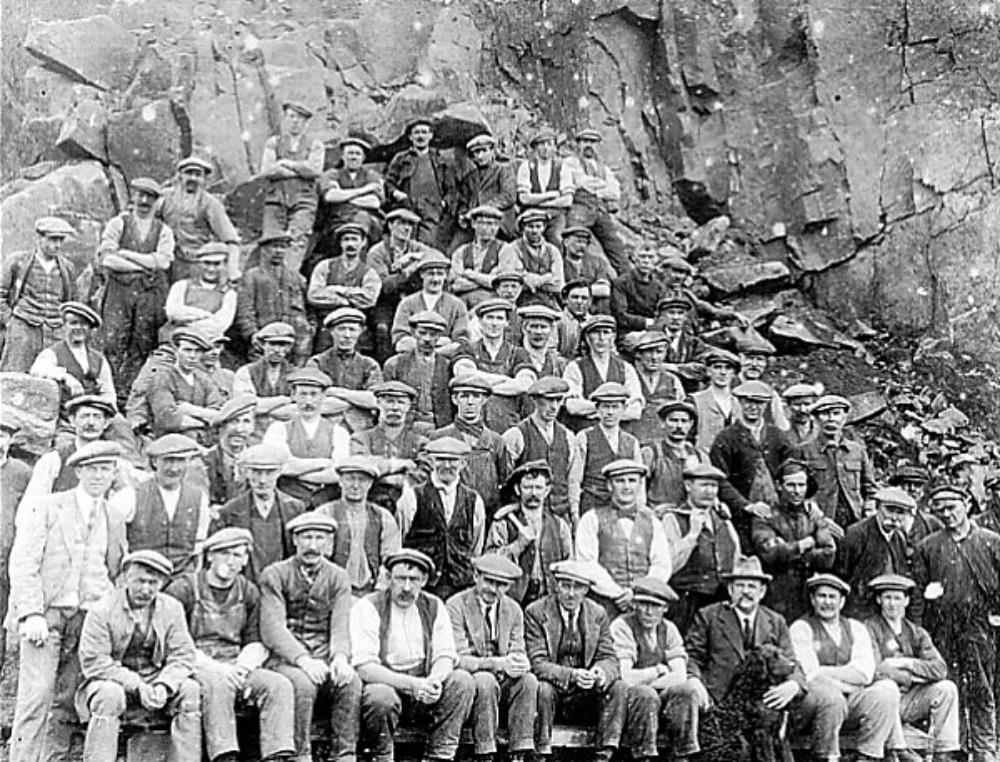

Cruickness Quarry workers 1920

Cruickness Quarry workers 1920

If you recognise someone in this photo or have any information, local stories or photos related to the quarries, please contact North Queensferry Heritage Trust by sending an email to: nqhtinfo@gmail.com

Your help in bringing the heritage of this important industry to life is much appreciated and will be acknowledged in any publication.

J.L. May 2022