North Sea Naval Bases

Bases in Scotland

By 1903 the growing threat from threat from a new German Navy in the North Sea had been recognized, and the Royal Navy decided that the growing threat form the new German navy in the North Sea should be tackled with a revised policy of ‘distant’ rather than ‘close’ blockade.

The traditional Royal Navy strategy in time of war had been to place a large fleet of ships outside an enemy harbour to form a close blockade. However the invention of the submarine made that approach very dangerous – a large static fleet could be wiped out by submarines. Instead the Royal Navy adopted a ‘distant blockade’ strategy – a large fleet was held on instant readiness in a well-guarded home port, from where they could launch an attack in open water if the enemy fleet took to sea. The submarine threat was much reduced when the fleet was underway, and able to travel much faster than a submerged submarine, so presenting a difficult moving target.

The problem with this approach was that the existing Royal Navy bases were all located along the south coast of England. They had been built to protect the English Channel from the old enemies of France and Spain.

New bases were urgently needed on the North Sea coast. Three sites were chosen: Scapa Flow in Orkney, Invergordon at Cromarty Firth and Rosyth in the Firth of Forth.

Scapa Flow’s natural harbour had been used many times for British exercises in the years before the War. It was chosen as the first base for the Grand Fleet, despite being unfortified.

Admiral Jellicoe, admiral of the Grand Fleet, was concerned about the possibility of submarine or destroyer attacks on Scapa Flow, so the base was reinforced, first with over sixty block-ships sunk to block the many small entrance channels between the islands, then with submarine nets and booms, minefields, artillery, and concrete barriers.

German U-boats made two attempts to enter Scaoa Flow, in 1914 and 1918. neither attempt was successful.

Invergordon had also been used by the Home Fleet in the 1900s. It offered a large deep water anchorage sheltered by the Cromarty Firth and an extensive existing dockside. A vast complex of fuel-oil storage tanks was added along with accommodation for a huge influx of naval and civilian personnel. The town’s population grew by 6,000 when people came to work in the dockyards, providing fast turnround repair facilities (the pre-war population was about 1,100.) It grew to around 20,000 during the war when an army camp was built nearby.

In 1913, base defences were added. Three 9.2-inch guns (to tackle large enemy warships) and six 4-inch Quick Firing guns (to deal with smaller, faster-moving vessels) were placed on the north and south headlands at the entrance to the Firth. These were equipped with defence electric lights, and the mouth of the Firth was obstructed by an anti-submarine boom.

In the Firth of Forth, St Margaret’s Hope had offered a sheltered haven from the days of sailing ships. It is believed to be the site where Queen Margaret landed when she first came to Scotland – hence the name.

Looking west across St Margaret’s Hope about 1900

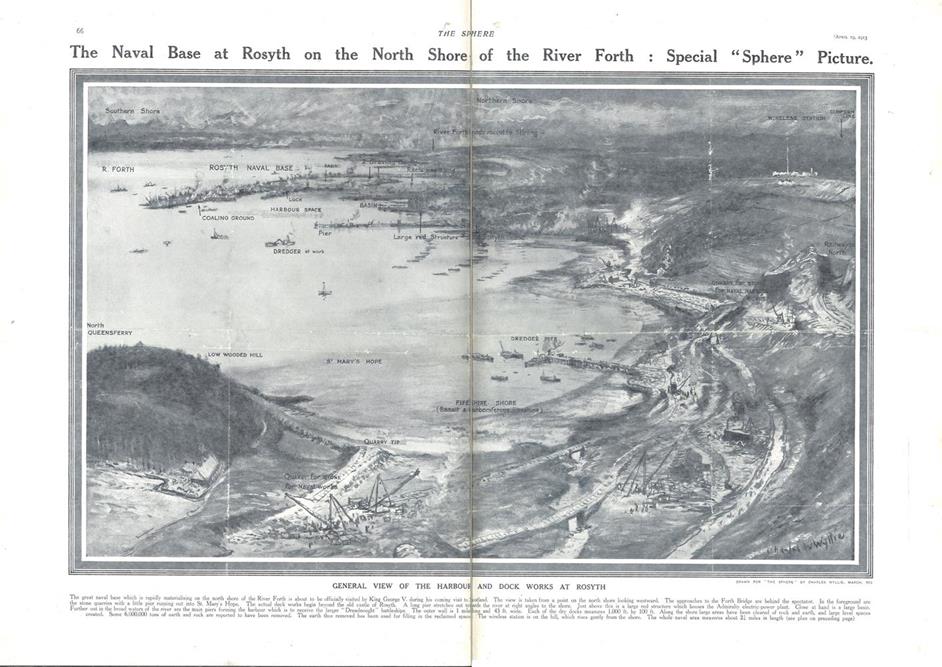

In 1903, land was purchased by the government and work started on the construction of a dockyard and oiling facilities, but it would be many years before the base was complete.

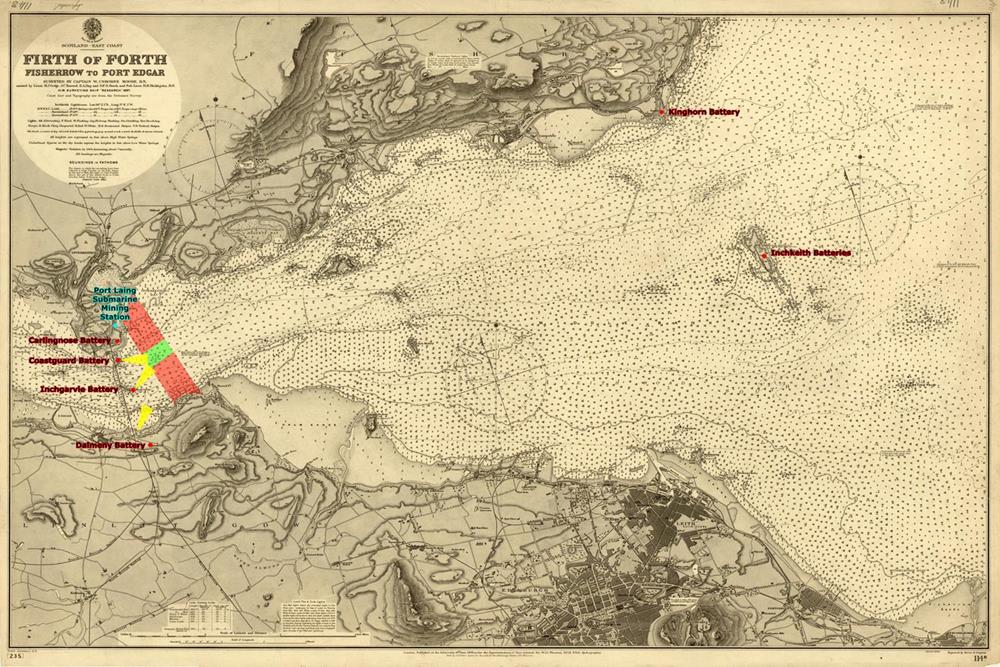

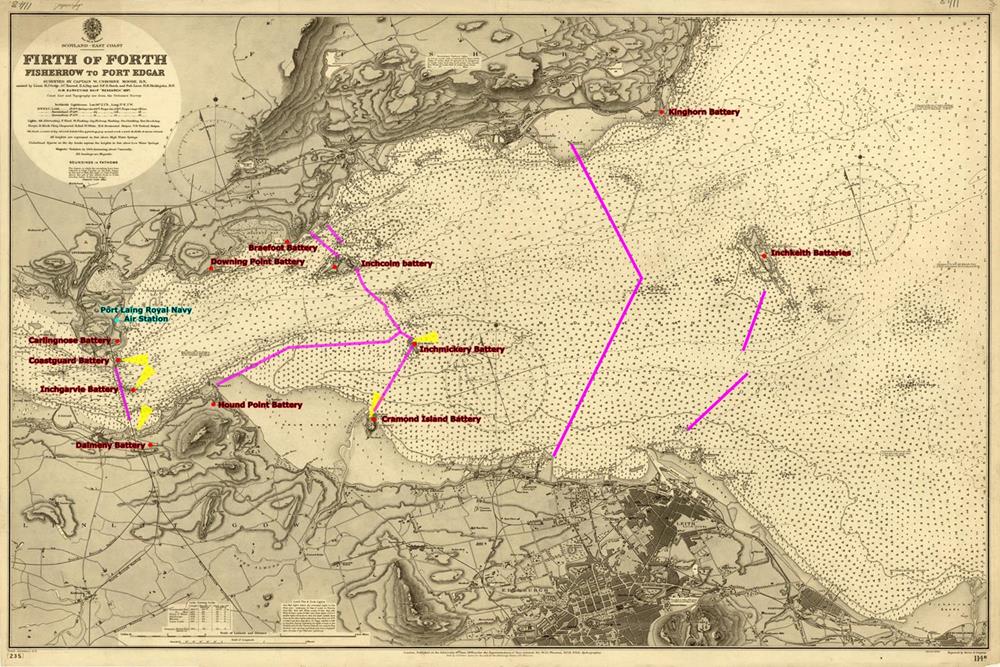

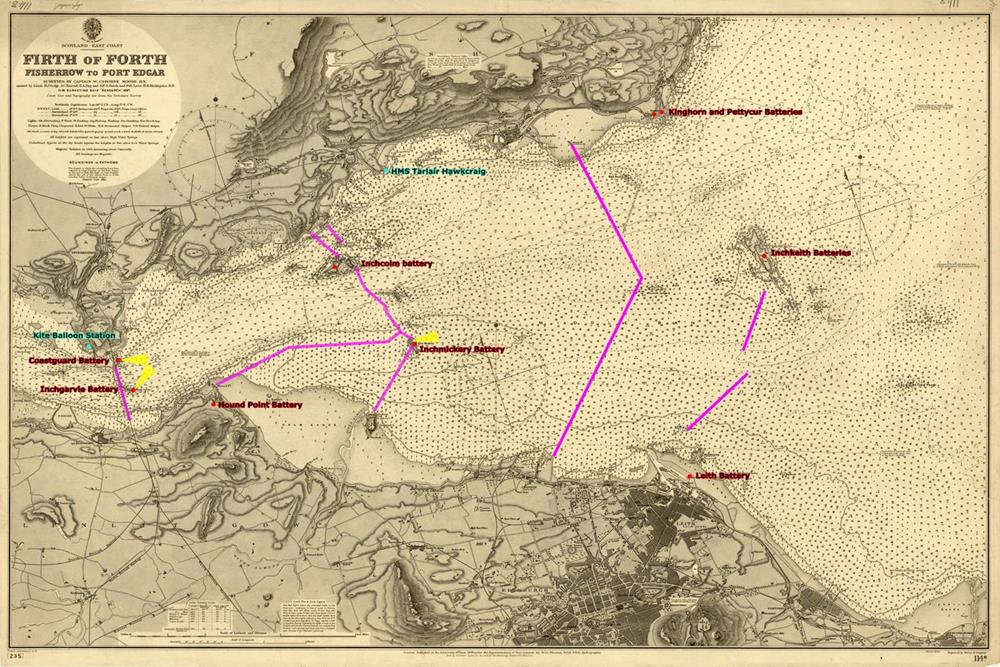

For centuries the Firth of Forth had been protected by fortifications and guns on various islands and shore batteries. Inchkeith was seen as the key defensive strong-point controlling shipping movements up and down the river.

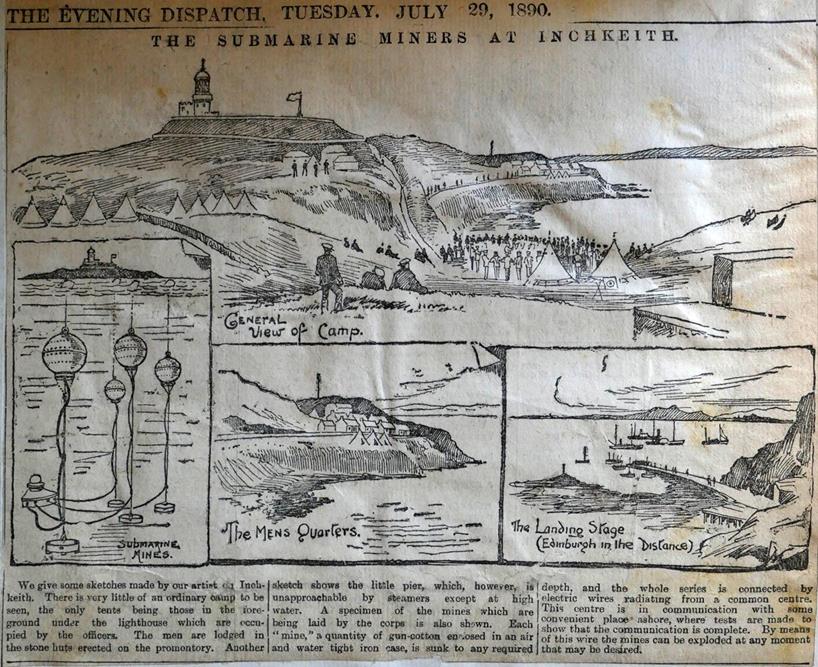

In Britain, the Government had noted the efficacy of torpedoes and mines in the American Civil War, and conducted a series of experiments into the potential of electrically-controlled mines to defend harbours. By 1870 the Submarine Mining Division of the Royal Engineers was created. Their mission was to be able to deploy defensive minefields in time of war across the mouths of the main Royal Navy harbours of The Medway, Portsmouth, Plymouth, Pembroke and Cork.

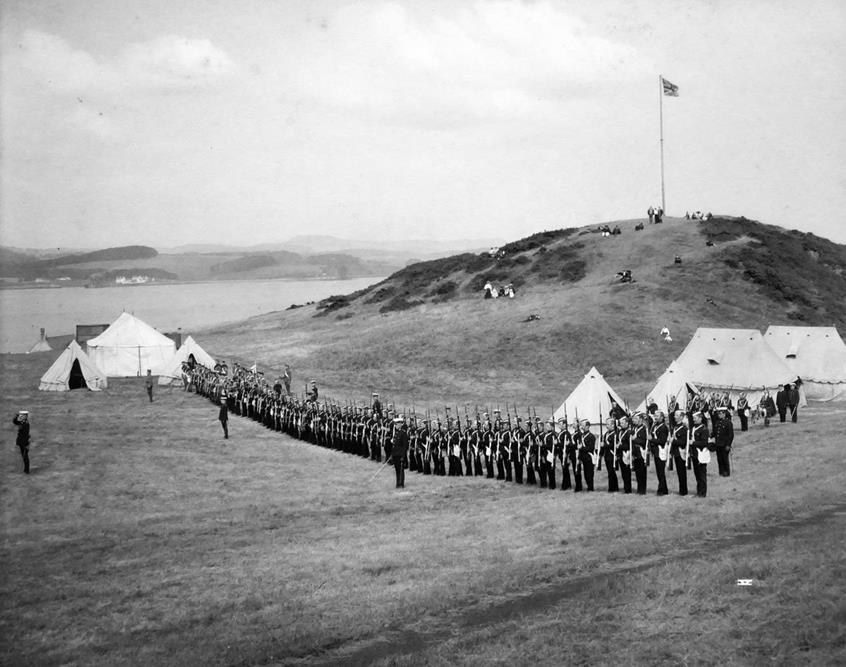

In 1880 the Government decided to extend the protection of defensive minefields to “commercially important estuaries” – the Humber, Clyde, Tay and the Forth. In 1887 A Submarine Mining Volunteer Division was raised in Edinburgh. They set up practice camps on Inchkeith.

In 1898 the Submarine Mining operation moved to a newly built permanent site at Port Laing in North Queensferry.

These complemented gun batteries in Inchgarvie and the Coastguard Station at North Queensferry.

In 1902 heavy gun batteries were installed at Carlingnose on the north and Dalmeny on the south to back-up the minefield.

In 1906 the Submarine Mining service was disbanded. The concept had been rendered obsolete by the submarine, which could sail through the “friendly channel” and wreak havoc upstream. (The volunteers became the precursors to the Territorial Army.)

A possible solution to the submarine threat came from Kittyhawk in North Carolina in 1903, when Orville and Wilbur Wright made the first flight in a powered aeroplane. Things progressed rapidly, and in 1909 Bleriot flew across the English Channel.

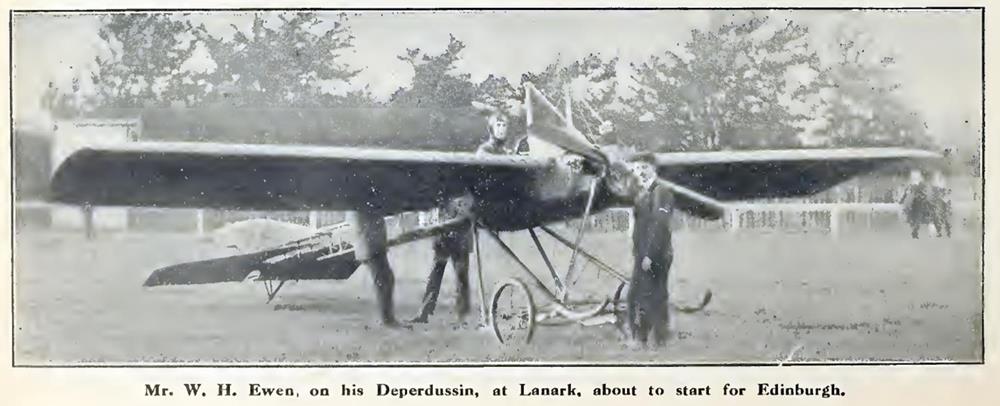

In 1911 – Scottish aviator W.H. Ewen flew across the Forth from Edinburgh, turned, flew back and landed safely!

Meantime work was proceeding on the new Dockyard at Rosyth. in 1912 the caissons for the dockyard gates were constructed at North Queensferry and floated upstream to Rosyth

In 1912 the Royal Flying Corps was established, with a Military and a Naval Wing. The Government announced the creation of a series of Air Stations, associated with the new east Coast Naval bases. The first naval air station in Scotland was at Port Laing, just along from the old Submarine Mining Station.

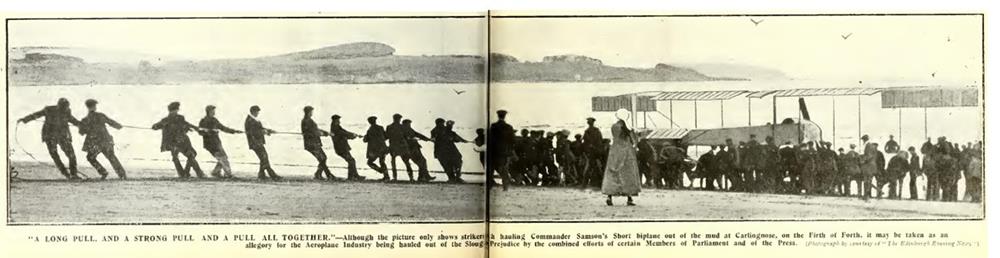

Their mission was to spot submarines underwater, by observing the wake and eddies left by their passage. They were based at Port Laing until January 1914, when they moved to Dundee. The combination of winds around the cliffs, and the sticky sand were not ideal at Port Laing. The owner of the land tried to put up the rent! And the MP for Dundee, was very keen on ships and planes – one Winston Spencer Churchill.

28th July 1914 – World War broke out.

The Navy flyers from Dundee were dispatched to provide reconnaissance in Belgium then in teh Dardanelles

The Royal Navy matched the High Seas Fleet by assembling the Grand Fleet – battleships based in Scapa Flow under Admiral Jellicoe, and Battle Cruisers at Rosyth under Admiral Beatty. Although Rosyth was still under construction, the Forth Defences had been significantly upgraded with layers of submarine nets and new gun batteries.

Anti-submarine nets were suspended from the Forth Bridge. These could be lowered to allow ship to pass over them. Further downstream, the nets contained gates, sections that could be moved by trawlers and guard-ships. There were gates at Oxcars and Black Rock.

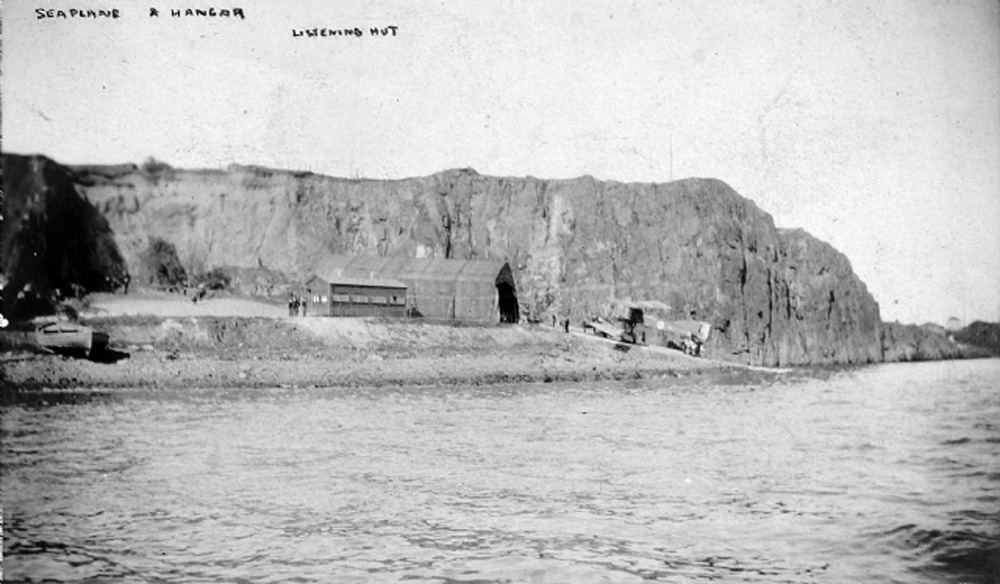

In 1915, an experimental anti-submarine station was opened at Hawkcraig, Aberdour. A seaplane was used to spot submarines, and the plane’s observer then manoeuvred a radio-controlled boat carrying explosives into position over the submarine. You can read more about this on the HMS Tarlair website.

This photo shows the seaplane hanger on the shore at Hawkcraig.

Work continued on the dockyard at Rosyth and in 1916, Port Edgar at South Queensferry was purchased as a destroyer base. While Battle ships and Cruisers could be left at anchor in the Forth, small destroyers were more comfortable when sheltered in penns.

The wounded from the Battle of Jutland in June 1916 were landed here and treated at Butlaw hospital South Queensferry. The dead were buried in the local cemetery.

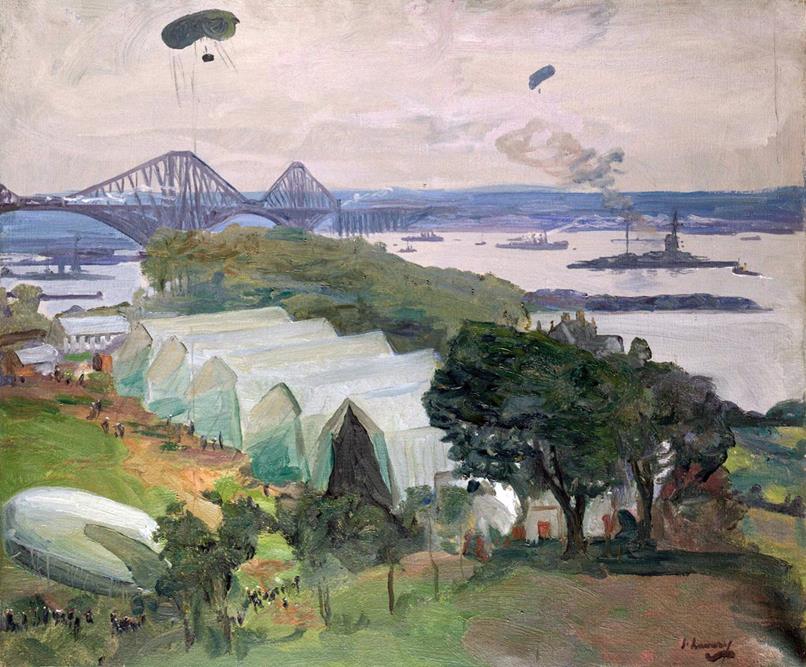

At North Queensferry, a Kite Balloon Station was opened in the summer of 1917. Both Beatty and Jellicoe had recognized the value of kite balloons, which carried an observer high above a ship, in sighting an enemy.

By 1918, the Forth Defenses were revised again, to allow ships to anchor to the East of the Forth Bridge. The entire Grand Fleet – Battleships, Battle-cruisers and Destroyers could now be accommodated in the Forth. Jellicoe had retired, and Beatty now had the entire fleet under his command.

English Channel Defences

While the Grand Fleet and the new bases secured the North Sea from the German Navy, it was still necessary to secure the approaches to the English Channel, to prevent elements of the German High Seas Fleet from breaking out into the Atlantic, or from interfering with British maritime trade and convoys to the continent.

The Dover Patrol was based at Dover, consisting mostly of destroyers, while a number of pre-dreadnoughts and cruisers were based at Portland Harbour.

In 1914 a new force was established at the existing port of Harwich, under the command of Commodore Reginald Tyrwhitt. The Harwich Force consisted of between four and eight light cruisers, several flotilla leaders and usually between 30 and 40 destroyers, with numbers fluctuating throughout the war, and organised into flotillas.

Also stationed at Harwich was a submarine force under Commodore Roger Keyes.

In early 1917, the Harwich Force consisted of eight light cruisers, two flotilla leaders and 45 destroyers. By the end of the year, there were nine light cruisers, four flotilla leaders and 24 destroyers. The combination of light, fast ships was intended to provide effective scouting and reconnaissance, whilst still being able to engage German light forces, and to frustrate attempts at minelaying in the Channel.

During the First World War, Immingham on the Humber was used as a submarine base for British D class submarines.

In February 1918, the 20th Destroyer Flotilla, a specialist minelaying flotilla was formed, based at Immingham under the command of Commander Berwick Curtis with his flagship HMS Abdiel, a fast mine-layer that could carry a load of 66 mines. Their mission was to maintain a mine-field in front of the German naval Bases at Heligoland, to keep the German High Seas Fleet confined to their bases.

On 1 August 1918, Abdiel was leading the 20th Flotilla on its way to lay minefield A67 when the flotilla ran into a German minefield, with the destroyers Vehement and Ariel striking mines. Ariel sank quickly with the loss of 49 of her crew, but Abdiel took the remains of Vehement in tow. (Vehement’s bow had been blown off by the explosion, which killed 48 of her crew). The attempt proved unsuccessful, however, with the tow having to be abandoned and Vehement was scuttled.

The Flotilla continued its minelaying operations until the end of the war, with Abdiel laying 6293 mines during the war.

One of the officers – midshipman Adam – kept a diary of his time with the 20th flotilla. He covers the destruction of Vehement and Ariel, and was also an eye witness at the surrender of the High Seas Fleet in November 1918, when the 20th flotilla joined the Grand Fleet in the Forth.

NQHT has commissioned an audio recording of his diaries, and you can listen to extracts HERE.