Scapa Flow

Transfer to Scapa Flow

A total of 70 ships surrendered in the Forth on 21st November 1918

5 battle cruisers: Seydlitz, Derrflinger, Hindenberg, Möltke and Van der Tann.

9 battleships: Friedrich der Grosse, König Albert, Kaiser, Kronprinz Wilhelm, Kaiserin, Bayern, Markgraf, Prinzregent Luitpold and Grosser Kürfurst.

7 light cruisers: Karlsrühe, Cöln, Brummer, Bremse, Emden, Frankfurt and Nürnberg.

49 destroyers:

No. 1 flotilla: G40, G86, G39, G38, S32 (5 in total) V30 struck a mine on the way across.

No. 2 flotilla: G101, G102, G103, V100, B109, B110, B111, B112, G104 (9 in total)

No. 3 flotilla: S53, S54, S55, G91, V70, V73, V81, V82 (8 in total)

No. 6 flotilla: V43, V44, V45, V46, S49, S50, V125, V126, V127, V128, S131, S132 (12 in total)

No. 7 flotilla: S56, S65, V78, V83, G92, S136, S137, S138, H145, G89 (10 in total)

No. 7 (Half) flotilla: S36, S51, S52, S60, V80 (5 in total)

Note: The German destroyers were designated by a letter to indicate the builder

| B | Blohm und Voss, Hamburg |

| G | Germaniawerft, Kiel |

| H | Howaldtswerke, Kiel |

| S | Schichau, Danzig |

| V | A G Vulcan, Hamburg |

The ships were inspected in the Forth on Friday 22nd November to ensure that their condition complied with the terms of the armistice. The transfer to Scapa Flow for internment took place in batches over the following five days.

Saturday 23rd November: 20 British destroyers escorted 20 German destroyers.

Sunday 24th November: a further 20 German destroyers escorted by 20 British destroyers.

Monday 25th November: 5 German battlecruisers and the remaining 9 German destroyers escorted by the 1st Battle Cruiser Squadron.

Tuesday 26th November: 5 German battleships and 4 German light cruisers escorted by 5 ships of the 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron.

Wednesday 27th November: 4 German battleships and 3 German light cruisers escorted by 4 ships of the 1st Battle Cruiser Squadron and 4 of the 3rd Light Cruiser Squadron.

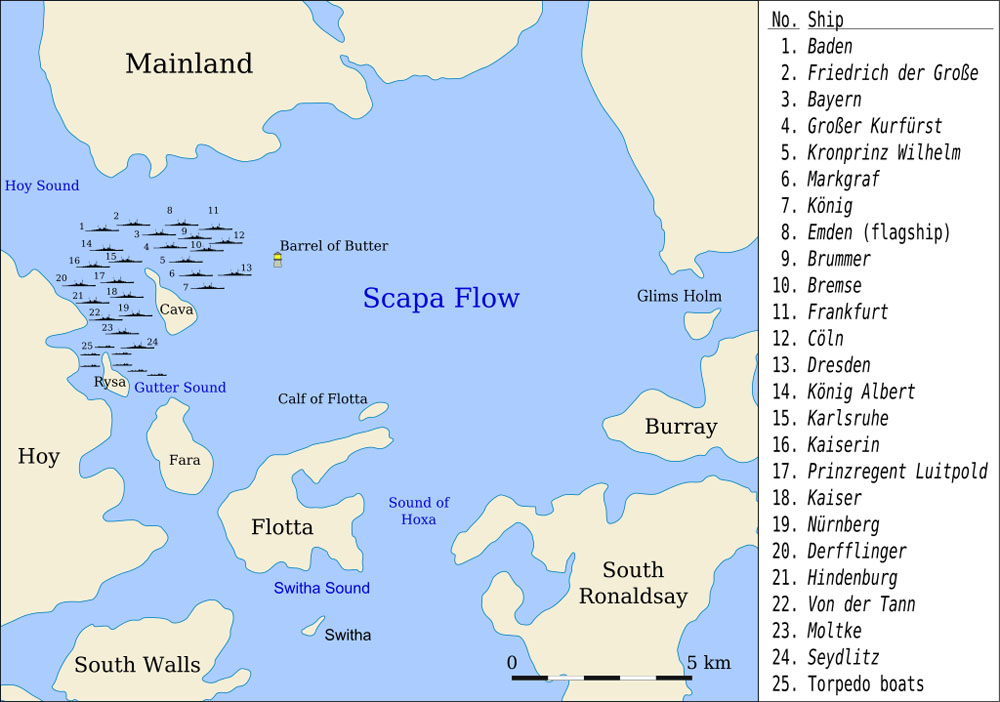

Anchorage in Scapa Flow

Once in Scapa Flow, the German ships were anchored in the Bring Deeps.

The “capital ships” were anchored individually, while the destroyers (referred to as Torpedo Boats in this map) were lashed together in “bundles” of two or three ships, to make then safer in the often storm-lashed waters of Scapa Flow.

On Sunday 3rd December, two transport ships – Sierra Ventana and Graf Waldersee arrived to start taking home surplus members of the ships’ crews, leaving them with care and maintenance skeleton crews, of about 200 officers and men on the battleships and battle cruisers and 12 to 20 men on each destroyer bundle.

On Monday 4th December, three more German ships were sent to Scapa Flow, arriving on Tuesday 6th December.

These were the battleship König, the light cruiser Dresden and the destroyer V129.

König was unable to take part in the surrender in the Forth, because she had leaking condenser tubes.

Dresden was leaking badly. She had been partially scuttled during the sailors’ revolt in October, and had to be refloated so could not join the main body of fleet at the surrender on November 21st.

The destroyer V129 was sent to replace V30 which had struck a mine on the way to Rendezvous “X”.

This brought the numbers up to 73.

About 20,000 officers and men had sailed the ships to Scapa Flow. 4,000 returned to Germany on 3 December, 6,000 on 6 December and 5,000 on 12 December, leaving 4,815 in the care and maintenance parties. These numbers continued to reduce as approximately 100 were repatriated each month thereafter. Von Reuter took the opportunity to return to Germany on the 12th December on leave! He returned on 25th January 1919.

On 10th January 1919 the battleship Baden was sent in place of the battlecruiser Mackensen. Mackensen was launched in April 1917, but construction work was halted from lack of material. The British mistakenly believed the ship to have been completed, and so had included the ship on the list of vessels to be interned.

There were now 74 ships interned in Scapa Flow as required by the Armistice.

Life at Scapa Flow

Food was sent from Germany twice a month but was monotonous and not of good quality. Catching fish and seagulls provided a dietary supplement and some recreation. A large amount of brandy was also sent over. Recreation for the men was limited to their ships, as the British refused to allow any of the interned sailors to go ashore or visit any other German ships. British officers and men were only allowed to visit on official business. Outgoing post to Germany was censored from the beginning, and later incoming post also. German seamen were granted 300 cigarettes a month or 75 cigars. There were German doctors in the interned fleet but no dentists, and the British refused to provide dental care. News was provided in the form of several-days-old newspapers. Rear-Admiral von Reuter had access to a British drifter at his disposal for visiting ships and issuing written orders on urgent business, and his staff was occasionally allowed to visit other ships to arrange repatriation of officers and men.

The conditions on the ships and lack of discipline struck all visitors. Many of the ships were under the control of Workers’ and Soldiers’ parties who refused to accept orders from their officers. Growing discontent often erupted into drunkenness, rioting and violence.

By the middle of June 1919, von Reuter was granted permission from the British to transfer his flag from the battleship Friedrich der Grosse to the light cruiser Emden, because he could no longer bear the clatter of mutinous sailors roller-skating on the battleship’s iron deck, which kept him awake.

German concerns about peace treaty terms

As the months rolled by, von Reuter became increasingly concerned by the slow pace of the peace negotiations in Paris, where the fate of the ships was proving to be a stumbling block. The French and Italians each wanted a quarter of the ships. The British wanted them destroyed, since they knew that any redistribution would be detrimental to the advantage in numbers they had compared to other navies.

In May 1919, learning of the possible terms of the Treaty of Versailles, von Reuter prepared detailed plans to scuttle his ships, but the indiscipline in the fleet made it impossible for him to take immediate action.

British concerns about scuttling

From the time of the German sailor’s mutiny in October 1918, the British had been ready to take action to seize the German ships if necessary.

At 6am on November 11th 1918, immediately after the Armistice was signed, but before its public announcement, Captain Marryat of the Royal Navy telephoned the Admiralty from Compiegne in France, to say that the German delegation had been advised that the Allies reserved the right to occupy Heligoland and enforce the terms of the Armistice if the mutinous sailors did not hand over their ships.

These concerns were not diminished once the ships were interned in Scapa Flow.

Both Admirals Beatty and Madden had approved plans to seize the German ships in case scuttling was attempted; Admirals Keyes and Leveson recommended that the ships be seized anyway and the crews interned ashore at Nigg Island, but their suggestions were not taken up.

Trigger events

In June 1919 several events combined to change the situation.

The First Battle Squadron prepared to board the German ships in force to check for signs that the fleet was preparing to scuttle. On 13 June Admiral Madden requested in person at the Admiralty a daily political appreciation from 17 June onwards so as to be prepared to take action, but there was no way of knowing what von Reuter’s attitude was to the proposed peace terms.

On 16th June, Admiral Fremantle submitted to Admiral Madden a scheme for seizing the German ships at midnight of 21/22 June, after the treaty was meant to be signed. Madden approved the plan on 19 June, but only after he was informed that the deadline for signing the treaty was extended to 19:00 on 23 June and he neglected to officially inform Fremantle.

About the same time, von Reuter received a copy of “The Times” which stated that the Armistice was to expire at noon on 21 June 1919, the deadline by which Germany was to have signed the Treaty of Versailles. He concluded that the British intended to seize the German ships after the Armistice expired.

On 18th June, two of the regular transports left for Germany carrying the last of the mutinous sailors from Scapa Flow. Rear-Admiral von Reuter now had enough reliable men who would carry out his instructions. That same day, he sent out secret orders from SMS Emden, paragraph 11 of which stated: “It is my intention to sink the ships only if the enemy should attempt to obtain possession of them without the assent of our government. Should our government agree in the peace to terms to the surrender of the ships, then the ships will be handed over, to the lasting disgrace of those who have placed us in this position.”

On 19th June, Fremantle read in a newspaper that the Armistice had been extended to 23rd June. He therefore postponed the planned operation to seize the German ships was postponed until the night of 23rd June, after the deadline to sign the treaty had expired.

He had been under orders from Madden for some time to exercise his battleships against torpedo attacks, which required good weather in order to recover the torpedoes. The weather forecast for the next few days was favourable so Fremantle ordered the First Battle Squadron to sea for exercises at 09:00 the next morning, 21 June. Fremantle later claimed that before he left Scapa he had unofficially informed von Reuter that the Armistice was still in effect.

Scuttle!

On the morning of 21st June, the first Battle Squadron and its escorting destroyers put to sea, leaving one British destroyer, a depot ship and a handful of trawlers and drifters to guard the German Fleet.

The closest British vessel to the German fleet that morning was the Admiralty drifter Sochosin On board was the artist Bernard Gribble making official drawings of the German Fleet. Gribble commented to the lieutenant commanding the drifter that all the ships were flying two flags, which had first appeared on SMS Emden the previous day. The upper was a white ball on a blue pennant, the lower a yellow and blue pennant. The flags seemed innocuous, and even if anyone on the British side could have translated the message, they simply read “Paragraph 11” “Confirm.”

However there meaning was far from innocuous – Paragraph 11 referred to von Reuter’s message of 18th June – “It is my intention to sink the ships if the enemy should attempt to obtain possession of them”.

“Paragraph 11, Confirm” meant prepare all ships for scuttling. The flags hoisted throughout the fleet indicated that everything was ready. All deck-top and internal openings – ventilators, scuttles, hatches, bulkheads and waterproof doors – were open, and sabotaged to prevent them from being easily closed.

At 11.20, the flags on Emden changed to “Condition Z” …Scuttle! Throughout the fleet, sailors open the seacocks – valves in each ship’s bottom designed to drain a ship when in dry dock, or to allow sea water to rush in. They then disconnected and jettisoned the control rods, to prevent the valves from being closed.

The first indication to the crew of Sochosin of the mass action was the sight of German sailors on Friedrich der Grosse and Frankfurt throwing baggage into the ship’s boats, then scrabbling aboard as the boats were lowered.

Sochosin headed towards Frankfurt, the closest ship, and ordered the German sailors to return to their ships. “We have no oars” replied the Germans, who had discarded them. A British sailor responded by throwing a few oars from Sochosin. German officers demanded to be taken aboard, but the boats that drifted alongside were kept off at gunpoint.

Another drifter Trust-on was in the midst of transferring supplies received from Germany to Emden when a crowd of German ratings demanded to be taken off as the ship was sinking. As Emden began to settle by the stern, von Reuter forced his way through the officers and men, and demanded to be taken on board Trust-on. He was given a curt refusal by the skipper, who headed off to the workshop ship Victorious.

There, Rear-Admiral Prendergast radioed Vice Admiral Fremantle, who ordered the recall of the First Battle Squadron and destroyers to Scapa Flow.

The tugs, drifters and trawlers set out to try and save those German vessels still afloat. Eighteen destroyers were cut from their moorings, drifted ashore and were beached. Four more destroyers were kept afloat by boarding parties. One light cruiser and the battleship Baden, were also beached.

The light cruiser Dresden was released her moorings and allowed her to drift ashore. Another light cruiser Nurnberg was boarded and taken in tow but she sank before she could be beached.

The battle cruiser Seydlitz was also boarded, but everything had been securely wired open, and she had to be abandoned.

At 14.30 the leading destroyers of the First Battle Squadron arrived back in Scapa Flow. Only two German battleships, one battlecruiser and four light cruisers remained afloat, but all were sinking.

In the struggle to stop the Germans from abandoning their ships, 8 were killed and 21 wounded.

By the end of the day, 51 ships were sent to the bottom of Scapa Flow.

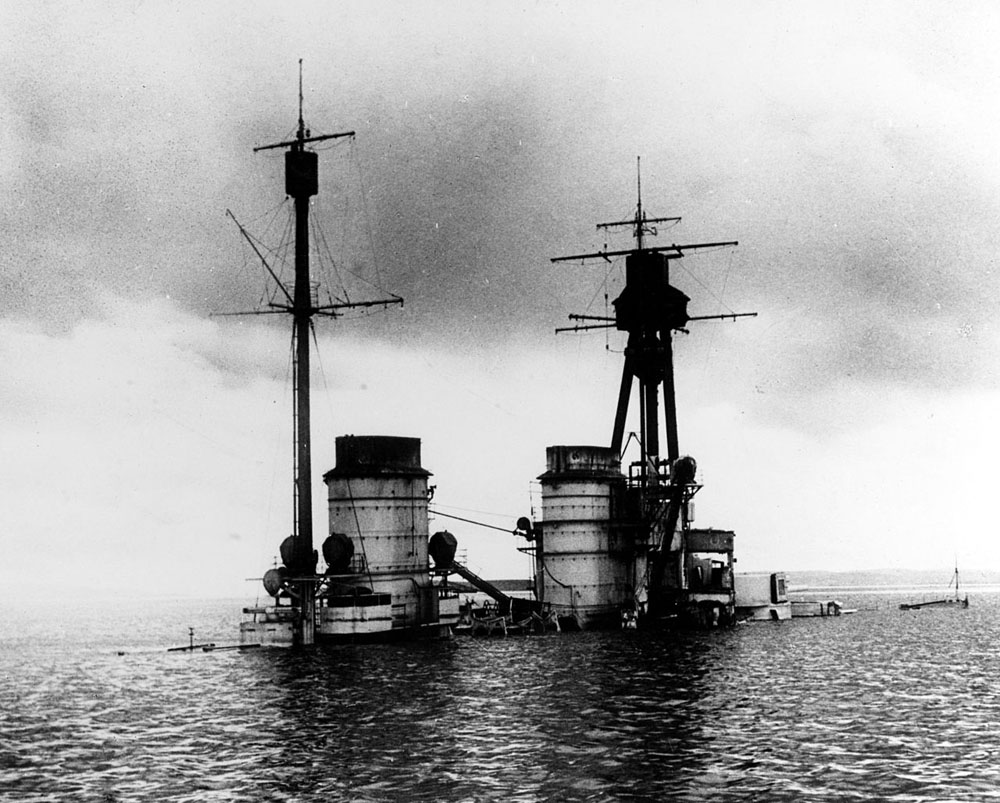

SMS Hindenberg scuttled in Scapa Flow,

Rear-Admiral von Reuter noted the times of sinking of the twenty-four capital ships.

| 1 | Friedrich der Grosse | 12:16 |

| 2 | König Albert | 12:54 |

| 3 | Brummer | 13:05 |

| 4 | Moltke | 13:10 |

| 5 | Kronprinz Wilhelm | 13:15 |

| 6 | Kaiser | 13:25 |

| 7 | Prinzregent Luitpold | 13:30 |

| 8 | Grosser Kurfurst | 13:30 |

| 9 | Coln | 13:50 |

| 10 | Seydlitz | 13:50 |

| 11 | Kaiserin | 14:00 |

| 12 | König | 14:00 |

| 13 | Von der Tann | 14:15 |

| 14 | Bayern | 14:30 |

| 15 | Bremse | 14:30 |

| 16 | Derfflinger | 14:45 |

| 17 | Dresden | 15:30 |

| 18 | Karlsruhe | 15:50 |

| 19 | Markgraf | 16:45 |

| 20 | Hindenberg | 17:00 |

Four were not sunk successfully, they were towed or drifted ashore and beached – Baden, Emden, Frankfurt and Nurnberg.

The destroyers

About half the destroyers were beached or sank in shallow water – they had been berthed closer to the shore than the capital ships.

| Flotilla Number | Sunk | Beached or sank in shallow water |

| No. 1 | G40, G86, G39, G38, V129 S32 | |

| No. 2 | G101, G103, B109, B110, B111, B112, G104 | V100, G102 |

| No. 3 | S53, S54, S55, G91, V70 | V73, V81, V82 |

| No. 6 | V43, V44, V45, V46, S49, S50, V125, V126, V127, V128, S131, S132 | |

| No. 7 | S56, S65, V78, S136, S138, H145 | V83, G92, S137, G89 |

| No. 7 (Half) | S36, S52 | S51, S60, V80 |

| Total | 26 | 24 |

The oil slicks from the sunken ships killed all sea life on the coasts for several years.

Fate of the German crews

The German crews were rounded up and placed in custody on British ships. At 14:30 on 21st June, Fremantle paraded von Reuter and his officers and accused them of treachery. Von Reuter considered that Fremantle would have done the same had the positions been reversed. He was made a prisoner-of-war, while his officers and crew were sent as prisoners to a military camp near Invergordon.

Privately, many of the British realized that von Reuter had done them a favour. The scuttling had immediately ended the squabbling over the division of the ships, and this speeded up the process of treaty negotiations. Peace was settled by the Treaty of Versailles which was signed on 28th June 1919 and took effect on 10th January 1920.

When the Germans were released in January 1920, they were hailed as heroes upon their return to Germany.

The fate of the ships

The Admiralty commissioned salvage advisers to examine the fleet; they reported that as the ships were undamaged, there would be little difficulty in raising them with compressed air. However the Admiralty announced on 23rd June that the sunken ships were no danger to navigation and “where they are sunk, they will rest and rust”.

The four floating capital ships were patched up and towed away.

Emden was towed to France in March 1920, and eventually broken up in Caen in 1926.

Frankfurt went to the USA and was sunk in aerial bombing experiments in July 1921

Baden was sunk by the Royal Navy as a gunnery target off Portsmouth in August 1921

Nurnberg was refloated in July and eventually expended as a target ship off the Isle of Wight in July 1922.

The beached destroyers had similar fates, sunk for target practice or broken up for scrap:

| 1 | G102 | to USA February 1920, sunk as bombing target |

| 2 | V100 | to France, scrapped 1921 |

| 3 | V73 | To Britain, scrapped 1922 |

| 4 | V81 | sank en-route to the breakers |

| 5 | V82 | To Britain, scrapped 1922 |

| 6 | V43 | to USA sunk as bombing target |

| 7 | V44 | salvaged by Royal Navy |

| 8 | V45 | salvaged by Royal Navy |

| 9 | V46 | to France, scrapped in Cherbourg 1924 |

| 10 | S49 | sunk Salvaged December 1924 |

| 11 | S50 | sunk Salvaged October 1924 |

| 12 | V125 | To Britain, scrapped 1922 |

| 13 | V126 | To France, scrapped 1925 |

| 14 | V127 | to Dordrecht, Netherlands |

| 15 | V128 | to Italy |

| 16 | S131 | sunk Salvaged August 1924 |

| 17 | S132 | to USA, sunk by gunfire of battleship USS Delaware, and destroyer USS Herbert |

| 18 | V83 | recovered by Royal Navy |

| 19 | G92 | To Britain, scrapped 1922 |

| 20 | S137 | To Britain, scrapped 1922 |

| 21 | G89 | recovered by Royal Navy |

| 22 | S51 | To Britain, scrapped 1922 |

| 23 | S60 | to Japan, later scrapped in the UK |

| 24 | V80 | to Japan, later scrapped in the UK |

Note – there are some discrepancies between sources as to the details of the fate of the destroyers.

Further information

You can learn more about the events in Scapa Flow in the Scapa Flow 1919 website which is run by Nick Jellicoe, the grandson of Admiral Jellicoe.

The sunken ships

Despite the Admiralty assurances, the sunken ships were a hazard to navigation, and in due course many of them were salvaged, and broken up for their scrap value.

Here is the story of the eventual raising of the scuttled ships.