Raising the scuttled ships

The sunken ships

Despite the Admiralty assurances, the sunken ships were a hazard to navigation, and in due course many of them were salvaged, and broken up for their scrap value.

Here is a ten minute YouView video of the scuttling and salvage

The Washington Naval Treaty

While the Treaty of Versailles imposed strict limits on the size and number of warships that the newly-installed German government was allowed to build and maintain, the USA, UK, France, Italy, and Japan all announced plans to expand the size of their navies. The USA planned to build a fleet of 50 battleships.

These plans were not welcomed by the U.S. public, who wanted to return to the pre-war policy of non-intervention. While Britain wanted new battleships, it could ill afford the exorbitant cost.

The US government eventually called an international conference, which in 1922 resulted in the Washington Treaty whereby the allied powers all agreed to limit the size of their navies. This resulted in the cessation of new shipbuilding, and the scrapping of many existing ships.

Therefore there was no interest in repairing any of the sunken ships. However they were a potential source of scrap metal.

Immediately after the war, there was a need for scrap metal to be recycled for post-war industry and rebuilding. Initially this was in plentiful supply for a few years, so the wrecks were ignored. However, as available stocks became exhausted, the price of scrap metal increased, and interest was shown in the sunken ships.

1922 – raising the first destroyer

In 1922, a local company – the Stromness Salvage Syndicate – bought a sunken destroyer and towed it into harbour at Stromness for breaking up. This was the first of the sunken fleet to be recovered.

As well as providing raw scrap steel, many of its components were recycled – for example the boiler tubes were polished and sold as thousands of curtain rods.

1923 – Robertson sets to work

In 1923 the Admiralty sold four destroyers to the Scapa Flow Salvage & Shipbreaking Company headed by a local man Mr J. W. Robertson. He purchased two concrete barges from the Admiralty, each with a lifting capacity of 1500 tons and linked them with steel girders to form a giant catamaran, which was positioned over a sunken destroyer.

Divers, wearing diving cumbersome diving helmets and air-lines to the surface, passed sixteen steel belts underneath the destroyer, which was resting on mud. While this made it possible to pass the belts under the destroyers, the disturbed mud obscured visibility, and the divers had to work by touch.

Cables suspended from the catamaran girders were attached to the belts and drawn tight at low tide. The plan was that as the tide rose, the destroyer would be lifted from the sea bed. The catamaran and suspended destroyer would then be towed towards the shore into shallower water. The destroyer would then settle on the bottom as the tide fell. The cables were then re-tightened, and the destroyer would lifted again at the next cycle of the tides. In this way the tides did the lifting; and the ship was gradually eased towards the shore.

The difference between high tide and low tide is about 10 feet (3 metres) in Scapa Flow. So a destroyer could be raised from 50 ft (15 metres) of water in five shifts.

Robertson also attached giant air bags to the destroyers. These fitted between the suspension cables. Robertson patented their design, and eventually had a total of four balloons; two with a lifting capacity of 100 tons and two of 150 tons.

1924 – Cox and Danks arrive

While Robertson was assembling his equipment, a second salvage contract was announced in January 1924. A Mr Cox of Cox and Danks had bought the remaining 20 destroyers along with Seydlitz and Hindenberg. Cox and Danks were ship-breakers and like Robertson had no previous experience of raising ships.

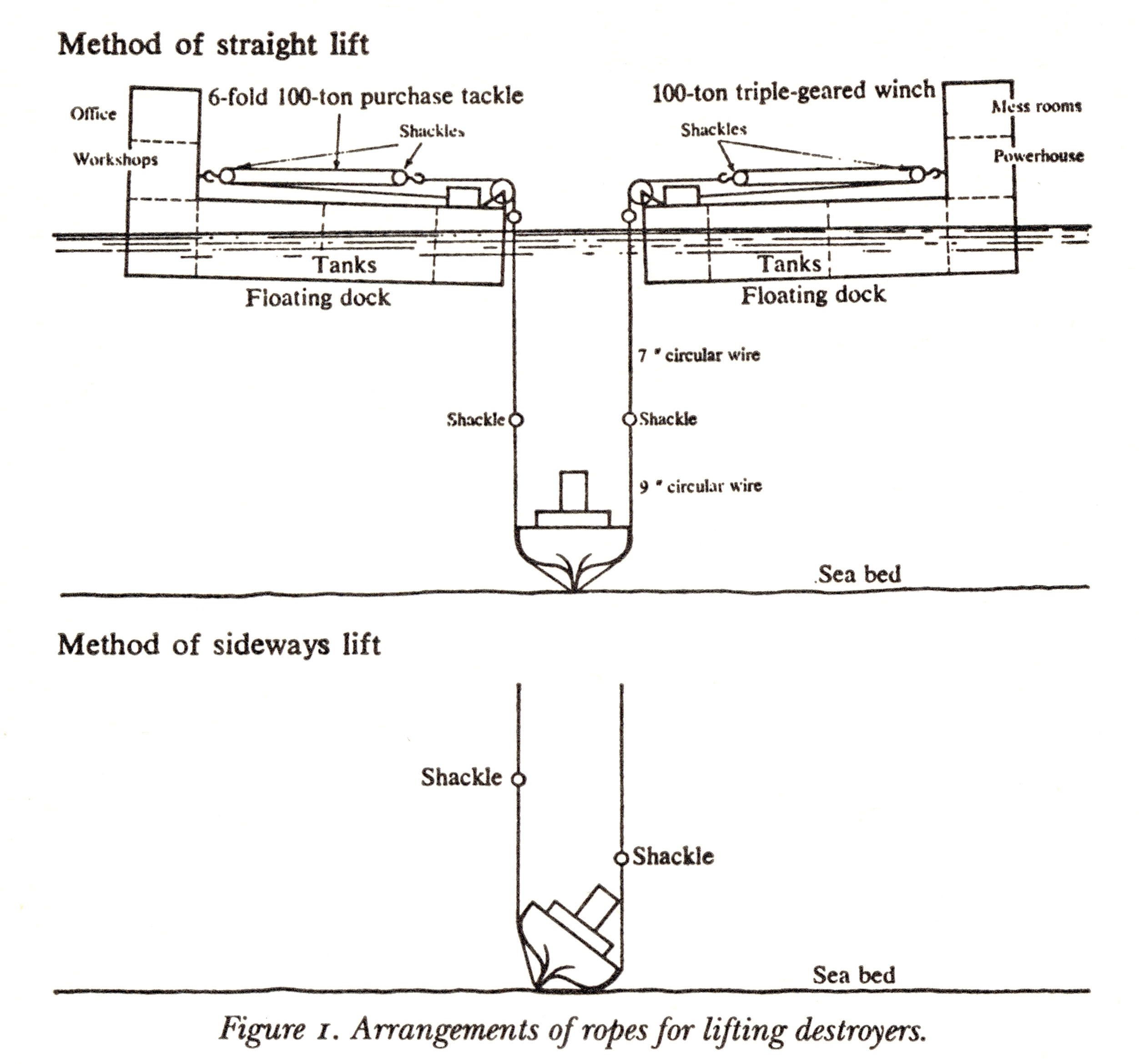

In Cox’s breaker’s yard in the Isle of Sheppey was a floating dock that had been surrendered to the Admiralty by the Germans in reparation for the scuttling of the High Seas Fleet. Cox purchased this U-shaped dock towed it to Scapa Flow and cut it in half to create two L-shaped docks, each fitted with twelve sets of lifting gear.

Cox decided to try to lift destroyer V70, which was upright in 50 feet of water (about 15 metres).

Cables were passed beneath the destroyer, then joined by shackles to lifting cables from the two docks. At low tide, the cables were tensioned, and then the rising tide lifted the destroyer clear of the bottom.

This British Pathe News Video shows the floating dock and lifting gear.

The initial plan was to use 3 inch (75 mm) chains that Cox already had in stock. These were hooked onto any convenient hole in the hull or superstructure of the destroyer. An initial attempt to raise V70 in March 1924 failed when links in the chains snapped where they passed over the pulleys on the edge of the floating docks.

New 9 inch (225 mm) steel cables with a breaking strain of 250 tons were purchased from Glasgow.

On Thursday 31st July 1924, a second attempt was made and this time V70 rose from the bottom with the rising tide. She was towed closer to shore and the process repeated four times until on Saturday 2nd August 1924 she was beached on a sandbank at Mill Bay.

There Cox discovered that she had already been stripped of everything of value from gun-metal torpedo tubes to bronze fittings. As the price of scrap steel had slumped unexpectedly from £5.00 to £1.50 per ton, Cox decided to make her watertight, pump her dry and use her as a floating workshop – renamed Salvage Unit No. 3.

Here is a British Pathe News Video of the raising of V70

Cox then started work on his second destroyer. This one was lying in her side, but Cox discovered that she could be rolled upright by lifting her as above, then by tightening the cables on one side while loosening those on the other side.

This technique would work even if the destroyer was completely upside down.

On August 24th, Cox was raising his third destroyer as Robertson lifted his first, S131 – the only time that two ships were raised on the same day.

By November 1924, Robertson lifted the last of his four destroyers. Cox had lifted six and now had the fleet to himself, but suspended operations over winter. From spring 1925 to April 1926, Cox raised his remaining fourteen destroyers, and then turned his attention to the big ships.

There were some light-hearted moments along the way – https://www.britishpathe.com/video/salvage-work-divers-salvage-musical-instruments/

Raising the big ships

1926 – SMS Hindenburg

The battle cruiser Hindenberg was the most obvious starting choice, as she was upright in 70 ft (21 metres) of water, with her deck just submerged at low tide. Cox decided to patch all the holes in the hull and deck, then pump her out so that she would float using her own buoyancy.

Quick setting cement was used to seal the sea valves on her bottom, and then work began on patching the 800 holes in her side and deck. These ranged from smallish portholes to one 40 ft by 20 ft (12 by 6 metres) weighing 11 tons that was needed to cover a corroded funnel hole in the deck.

In August 1926, the patching was complete and pumping started. It was soon found that the patches were leaking. They had been sealed using tallow, and the local saithe having developed a taste for tallow had nibbled away the packing. The patches had to be removed and repacked with a mixture of tallow and cement powder, which the saithe found unpalatable!

On 24th August pumping resumed, but work had to stop when a gale drove destroyer G38, which was being used as a breakwater, into the side of the ship, damaging some of the patches.

Several more attempts succeeded in lifting the ship, but she could not be stabilised, and she snapped the restraining hawsers. In September 1926 it seemed that success was in sight. Pumping resumed after divers jammed open internal bulkhead doors, allowing water to drain between compartments and maintain the ship’s trim. She rose to the surface and was moored to the floating dock. However an overnight gale set the dock rolling, and damaged the generators that powered the pumps. The ship had to be allowed to sink again level. Further attempts were abandoned as winter set in, and Cox turned his attention to the battlecruiser Moltke.

This British Pathe News Video shows work on a raised destroyer, and the failed attempt to raise Hindenberg

1926 – Moltke

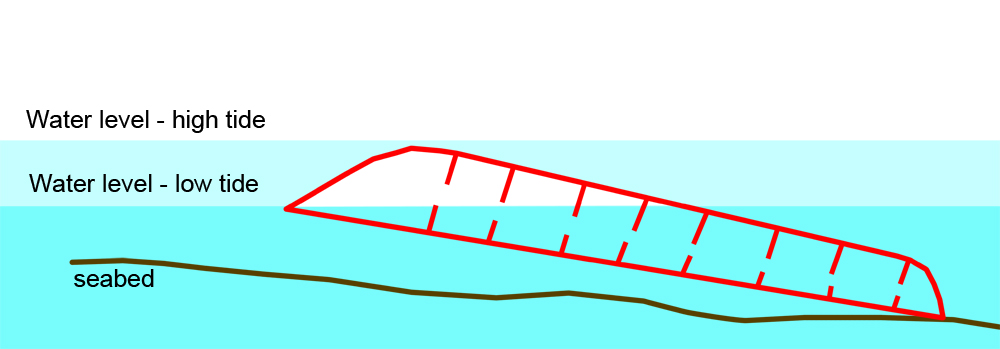

Moltke was lying bottom up in 78 feet (24 metres) of water just awash at low tide. Cox decided to raise her upside down by sealing all the bottom valves, and pumping in compressed air. This would push water out through the deck openings and she would then rise to the surface.

Concrete was used to block all the valve openings and lower torpedo tubes. Then in October 1926, compressed air pumping began. Ten days later the fore end of the ship broke surface, but the stern was still on the bottom, and she had developed a list. It was also found that she was not watertight, so she was allowed to settle on the bottom again.

Overcoming the buoyancy problem

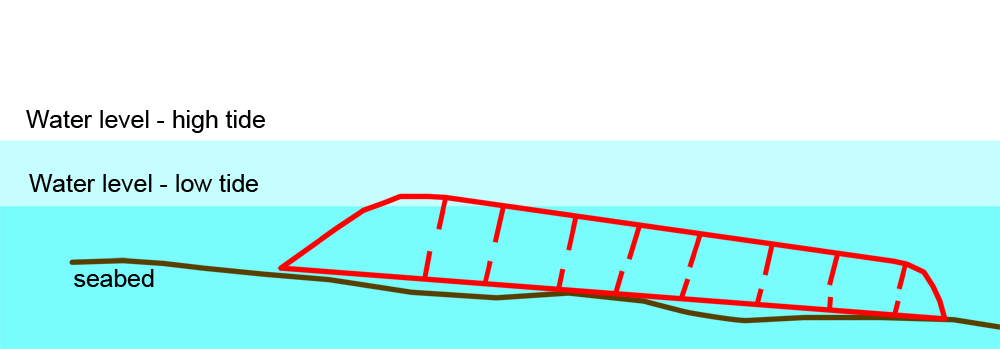

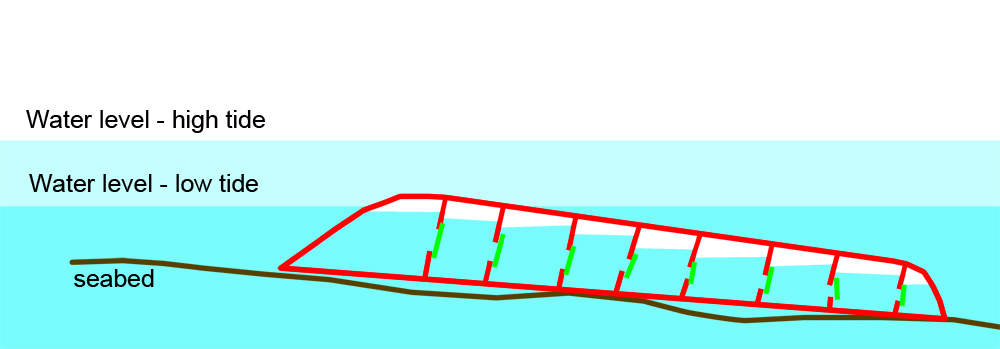

Here is the ship lying upside down on the sea bed. The hull has been sealed, but the internal bulkhead doors are open.

When compressed air is pumped into the ship, water is pushed down from the highest point, creating one large bubble inside the ship.

Here the left hand end will rise, but the right hand end will remain on the sea bed.

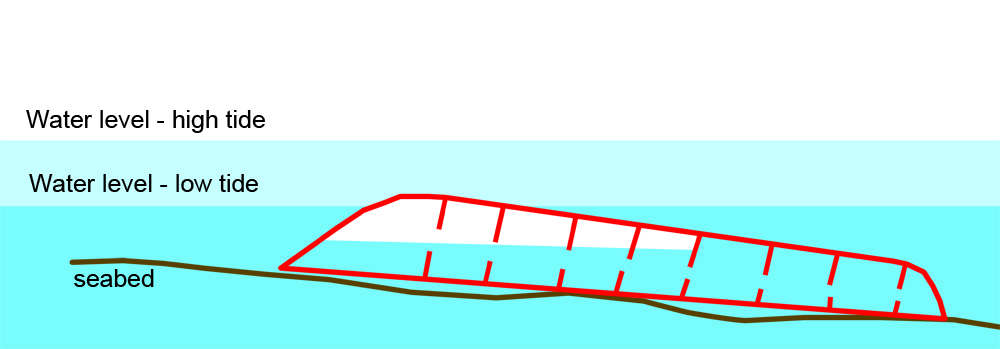

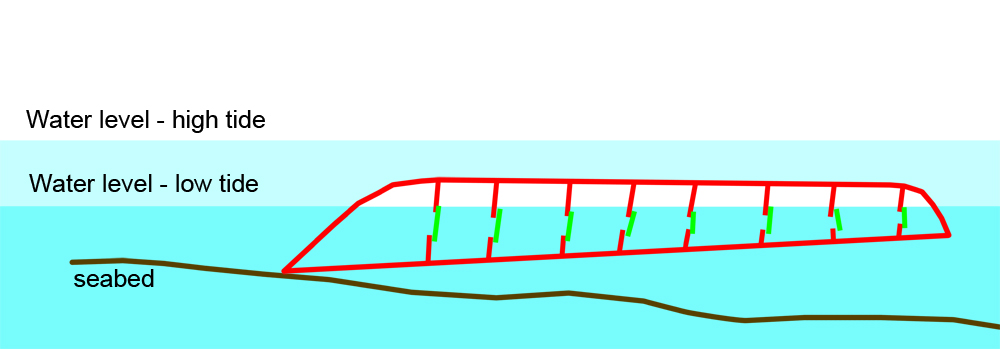

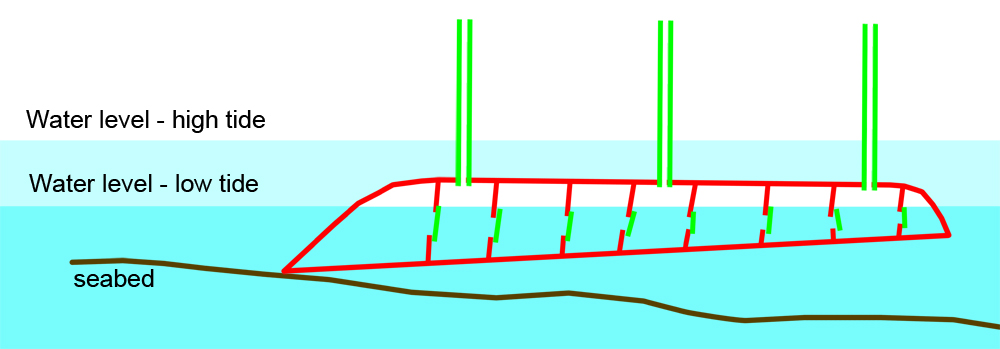

After sealing the internal bulkheads, compressed air can be pumped into each of the internal chambers,

adjusting the buoyancy so that the ship will rise evenly.

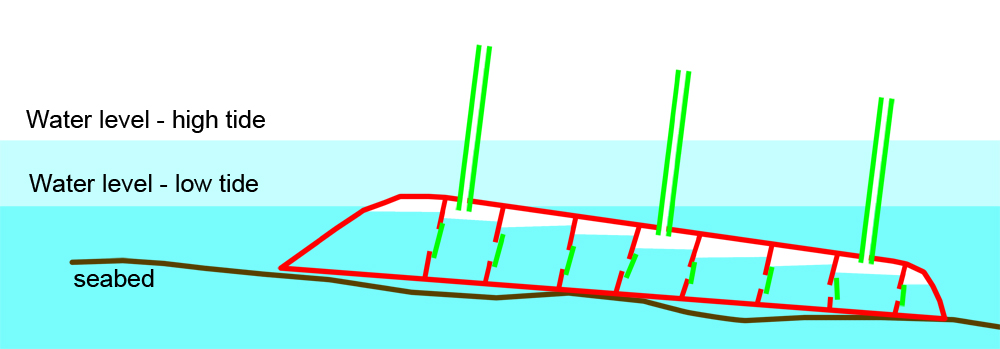

Air locks are fitted at two locations in the ship. These are steel tubes with double-door chambers at the top and bottom. They are welded to the hull of the ship, and then a hole is cut through the hull at the bottom of each airlock. The top of the airlock is above the high water level, so divers can climb up a ladder to the top of the air lock, then climb down inside the air locks. Once inside the bottom chamber, the upper door is closed, the chamber is are charged with compressed air to match the pressure inside the ship. The bottom door is then opened, and the divers can enter the ship to work on closing bulkheads and sealing leaks.

At the end of a shift, the divers re-enter the bottom chamber of the airlock, and close the bottom door. The pressure in the bottom chamber is slowly brought back to normal air pressure. Slowly so that dissolved gases in the divers’ bodies can escape without forming dangerous bubbles; this called depressurisation.

The divers can then open the upper door of the bottom chamber and climb back out of the airlock.

After nine months of work, Moltke was raised on 10th June 1927. She gradually rose from the sea bed, then as she rose, the internal water pressure decreased allowing the compressed air to expand, push out more water and increase her buoyancy push so that she surged to the surface in a welter of foam with the hull 20 feet above the water. One of the men in an airlock commented “I don’t know about lifebelts, its flaming parachutes we want up here!”

Here is a film clip of the raising of Moltke.

On 16th June 1927, tugs began to tow Moltke to the yard at Lyness, but she suddenly stopped and the tow line parted. Divers discovered that one of her 11 inch gun barrels had swung down and the muzzle had dug into the sea bed. The guns were blasted free on 17th June and she was successfully beached off Lyness pier.

The airlocks were removed and everything worth moving was removed from her insides – 3000 tons of assorted metal.

By Friday 18th May 1928, Moltke was ready for her last voyage. New smaller air locks were fitted along with a kitchen, bunkhouse and mess-room for her crew and a power house with air compressors to maintain pressure inside her hull as she was towed by two tugs, upside down the 200 miles from Scapa Flow to Rosyth and the only dry dock in Scotland that could handle her.

After a smooth start, they ran into bad weather which set Moltke rolling, releasing great bubbles of compressed air. She sank 6 feet lower in the water. Eventually the weather improved, the compressors restored the buoyancy and the journey south continued.

Problems in the Forth

In the Forth, arrangements had been made for an Admiralty pilot to meet the tugs off Inchkeith. However a Firth of Forth pilot arrived first, and an argument ensued. A 5 knot tide was carrying Moltke and the tugs upstream towards the Forth Bridge, with the tugs on one side of the central pier and Moltke on the other. The tow rope snagged on Inchgarvie and had to be cast off leaving Moltke to drift under the Forth Bridge. Happily she passed safely under the central span; the tugs got her back under control and she was delivered safely to Rosyth. There she was handed over to the Alloa Shipbreaking Company to be broken up for scrap.

1927 – Seydlitz

Back in Scapa Flow, work had already started on raising Seydlitz. She was lying on her side in 50 feet (15 metres) of water, with her port side 25 feet (8 metres) above water, looking like a small island.

Cox planned to raise her like Moltke, but to bring her up sideways. He began by removing 1800 tons of armour plating from her exposed port side, to lower her centre of gravity. This left a more or less flat space on which he constructed a set of airlocks.

He then had to seal lots of openings in her deck -funnels and ventilators and hatches – using large timber patches.

In June 1928, everything was ready. Eight airtight compartments had been formed that could be individually pressurised to adjust the ship’s trim as she rose. However, when compressed air was deployed, Seydlitz came up dead level, then there was a series of explosive concussions as internal bulkheads gave way, and she sank to the bottom again, rolling further on to her deck. Removing the armour plating had upset her balance, and weakened her structure.

For four months divers laboured to remove all her upperworks, to allow her to be raised upside down like Moltke.

In October 1928, the compressors started again, but she listed and rolled even further. In the following weeks, she was test-raised 40 times, but always had a dangerous list, so had to be sunk again. Finally she was part -lifted while some scrap boilers were placed on end under her low side, and filled with quick-setting cement to form a set of bollard. Seydlitz was then gently lowered and finally settled upside down on an even keel.

She was eventually raised in November 1928, towed to Lyness and beached. All her heavy machinery was removed, and the forward gun turret. Workmen then had to replace the missing armour plating on her port side with sand bags to maintain her balance.

By May 1929 she was ready to be towed to Rosyth. There were a few mishaps at first with two groundings. These were caused by a German tug using a sounding-line to measure water depth which was marked in metres, while the charts were marked in fathoms. A new sounding line was made, and the journey continued through stormy seas. It took seven days to reach Rosyth dockyard rather than the expected 3-4 days.

A Video clip of Seydlitz on her way to Rosyth

1928 – Kaiser

While Seydlitz was being stripped in Lyness, work started on preparing to raise the battleship Kaiser. She lay upside down in 150 feet (46 metres) of water with her hull 20ft (6 metres) below the surface at low tide.

Airlocks were fitted, sea-cocks sealed, internal bulkheads closed, and the gun turrets blasted off.

On 20th March 1929, the compressors were started, and Kaiser rose to the surface – the easiest of all the lifts.

She was taken to Lyness, gutted and then towed to Rosyth for final dismantling.

Although the lift had been easy, one of the divers was killed when he stumbled and fell in shallow water while closing a watertight door. He was quickly brought the surface, where it was discovered that the weight of his diving gear and ballast weights had asphyxiated him, despite having a good air supply.

This is a video of Kaiser after being raised in Scapa Flow

1929 – Bremse

Bremse and Brummer were fast cruisers designed for mine-laying. Bremse had been boarded at the time of the scuttling by a British naval party, who tried to beach her, but on the way she turned over and sank. She was in 75 feet of water on a sloping sea-bed with her bow showing above the surface and her stern perched on a rock at the edge of a steep precipice.

She was fitted with air locks, sealed and patched. However the work was plagued by a series of fires and explosions, because she contained much more oil than any of the other ships. When she was eventually raised in November 1929, another fire broke out while her oil-fuel tanks were being cleaned. The fire spread throughout the ship, and although it was brought under control, the heat caused so much damage that she was considered unsafe, and so was taken to Lyness and broken up there rather than risking the long tow to Rosyth.

1930 – Hindenberg again

In January 1930, another attempt was made to raise Hindenberg.

Remember, she was sitting the right way up, with her main deck just awash at low tide; so the plan was to pump water out until she floated right way up.

Divers examined her patches and reported that 500 were still watertight, the other 300 had to be repaired or replaced.

The massive forward gun turret, mast and superstructure were all removed to improve her stability, and a huge concrete wedge was fitted under her stern at the port side to stop her turning further. This wedge was made from the engine-room section of a destroyer which was towed out, positioned and then filled with 600 tons of concrete.

Steel cylinders, seven feet (2.1 metres) in diameter and 20 feet tall (6 metres) were fitted over each of the four hatches on Hinderberg’s main deck. These upper end of these cylinders were above the high water mark, so the cylinders provided easy access to the ship’s interior for divers and equipment.

By the end of June everything was ready to pump her out. She started to rise, but then started to list and sank again. Divers investigated and discovered that the problem was the pump discharge pipes were under water. Adjustments were made and the pumps started again with a diver monitoring progress. 30 feet (10 meters) under water in pitch darkness, his arm was sucked into a pump inlet pipe. The pumps were stopped, and water was let back in to the ship to release him. Apart from shock he had no ill effects. The pups were started again and on 23rd July 1930 Hindenberg finally rose to the surface. On 24th July she was beached in Mill Bay. On 23rd August 1930 three tugs took her in tow to Rosyth where she arrived three days later after an uneventful final voyage.

Here is a video clip of divers working on SMS Hindenberg

and the eventual raising of the ship.

1930 – Von der Tann

Before Hindenberg left Scapa Flow, work started on the battlecruiser von der Tann. She was upside down in 90 feet (27 metres) of water, with her hull under 24 feet (7 metres) of water at low tide.

She was tackled like Kaiser, but work was difficult because the air inside was foul and oxy-acetylene cutting started small fires. Eventually chemists provided a liquid fire-retardant spray so work could proceed. All seemed well until about six weeks later, and explosion occurred in a compartment that had not been treated. Men were blown about and three were trapped behind a jammed door. They were rescued by cutting through the door. After being treated for burns and bruises they were all back at work again within days.

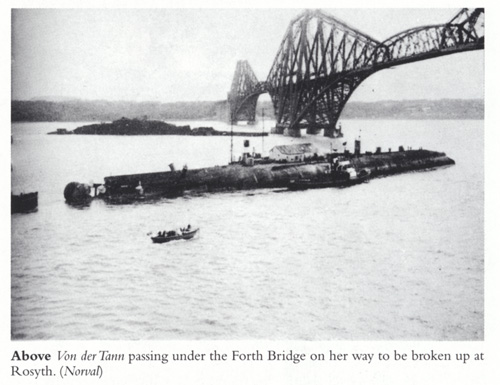

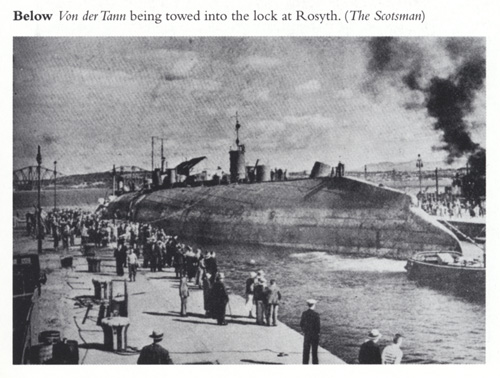

Von der Tann was raised on 7th December 1930, and beached on Cava on 5th February 1931 before being towed to Lyness once the weather improved. She was later towed to the dry dock in Rosyth and broken up from 1931 to 1934.

Video of von der Tann on her way to Rosyth

1931 – Prinzregent Luitpold

The last ship that Cox tackled was the battleship Prinzregent Luitpold. She was lying upside down in 105 feet (32 metres) of water, with 36 feet (11 metres) of water over her hull – the greatest depth tackled so far.

A total of 14 airlocks were fitted to allow her to be divided into enough airtight compartments. Deeper water meant greater water pressure, so divers could work for less time, and had to spend longer decompressing after each shift.

The airlocks were constructed in 10 foot (3 metre) sections. They tapered from 8 feet (2.4 metres) at the base to 4 feet (1.2 metres) at the top entrance, and were braced with so many wire stays that they looked like a spider’s web.

They had similar problems to those encountered on von der Tann, with small fires and smoke obscuring visibility.

On 27th May 1931, a violent explosion blew out a bulkhead and several men struggled to escape rising water. Mr Tait, a carpenter was knocked unconscious and drowned. The cause of the explosion was never determined.

On 12th June 1931 the ship was raised successfully, the funnels were blasted off and she was towed to shallower water and beached resting on her conning tower. The hope was that the conning tower would be forced up into the hull as the tide fell, to allow her to fit the dry dock. However the conning tower dropped out again as the tide rose. Eventually it was secured by three huge wire shackles. She was then towed to Lyness and lay alongside von der Tann, to be part stripped before three tugs towed her to Rosyth where she reached Rosyth dry dock on 11th May 1932.

Video of Prinzregent Luitpold

1934 – Metal Industries.

Cox had been raising ships in Scapa Flow for eight years, and while his scrap-metal business was very profitable, the ship raising business had left him £10,000 out of pocket, so he decided to retire after raising 26 destroyers, 6 battleships and 1 light cruiser. He spent much of is time in retirement giving lectures on his work for the benefit of charities.

Cox had bought the sunken ships from the Admiralty, he bore the cost of raising and insuring them, and then sold them, once delivered safely to Rosyth, to what had started life as the Alloa Shipbreaking Company, and eventually became Metal Industries, under the chairmanships of Robert Mc Crone.

Mc Crone had watched Cox’s activities and reckoned that with a cash injection to buy new equipment he could improve the efficiency of the ship raising business and make it turn a profit.

He hired all of Cox’s men, purchased “Bertha” a salvage vessel, new compressors, and was able to supply his own oxygen gas for cutting steel – this had been a major expense for Cox.

1934 – Bayern

The first ship that Mc Crone’s tackled was the battleship Bayern, purchased from the Admiralty for £1,000.

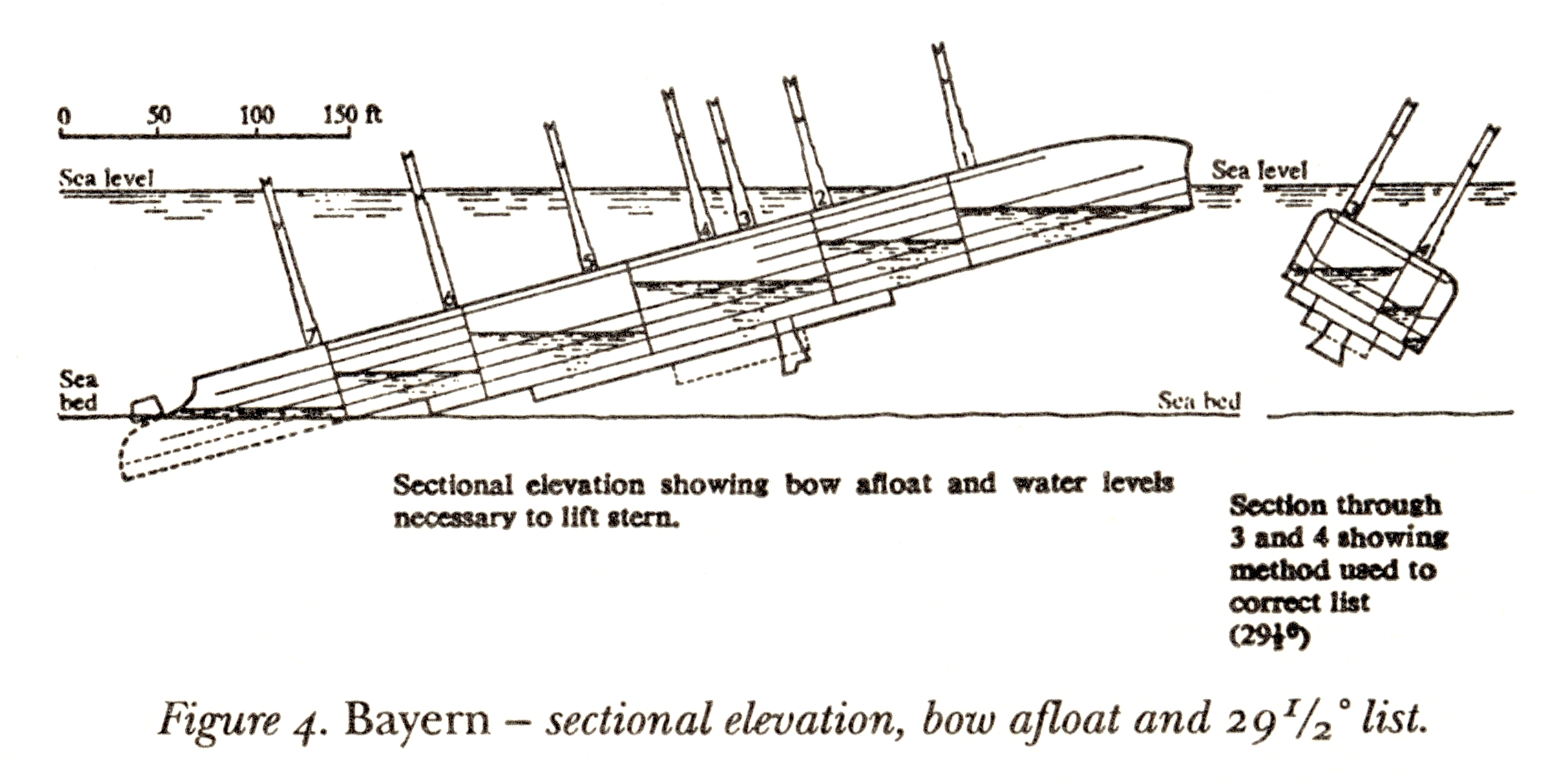

She was lying upside down in 120 feet (37 metres) of water with 65 feet (20 metres) over her bow and 85 (26 metres) over her stern. This required airlocks of 70 to 90 feet (22 to 28 metres) in length.

The ship was then divided into seven separate compartments to manage trim and stability. This involved a huge amount of work in pressures of 40 to 55 lbs per square inch (2.75 to 3.8 bar) cutting and blanking pipes, blocking ventilators, strengthening doors, sealing valves. . One man died from heart strain when he left a decompression chamber too soon.

After several attempts Bayern was raised on 1st September 1934. As she rose the compressed air expanded displacing more and more water until she shot to the surface within 30 seconds with columns of water shooting up as the air rushed out. Like the others she was towed to Lyness, and stripped before being taken to the breakers at Rosyth.

Video clip of Bayern in the Forth – first 25 second

1934 – König Albert

In October 1934, divers surveyed the battleship König Albert. She was upside down with her superstructure and turrets buried in soft mud in 135 feet (41 metres) of water.

Air locks 100 feet (30 metres) long were required. These required calm seas to fit – rare in Scapa Flow over winter. The first was fitted in November 1935, the eight and last in April 1935.

She had suffered more internal damage to bulkheads than the previous ships as she sank and turned over in such deep water, so took longer to seal.

On 31st July 1935 she rose in the biggest eruption of air and water yet seen. The next day she was towed to shallower water and beached with her funnels, bridge and turrets touching bottom. These were later blasted away and the hull towed to Rosyth.

Video of the raising of König Albert

Armour plate to Germany

About the time that Cox handed over to Metal Industries, Hitler had given orders that German tugs were not to be used for the ignominious task of raising German ships for scrap. Their place was taken by Dutch tugs.

However the steelworks at Essen who were working on Germany’s new fleet, were very happy to purchase the armour plate recovered from the ships at Rosyth, which was sold on the world market where there was a steady demand.

Hitler’s government also made enquiries about the guns recovered from the sunken ships for “use in coastal defence”! The Admiralty suspected that they were actually wanted as ship’s guns and blocked their export. The foreman at Rosyth was ordered to mutilate the barrels and breeches of all the guns, just in case.

1935 – Kaiserin

The exact position of the battleship Kaiserin was unknown, but she was found by sweeping about three quarters of a mile off Cava, in about 140 feet (42 metres) of water. She was of the same class as König Albert so was a relatively known quantity. The first airlock was fitted in July 1935 and the eighth and final by the end of October 1935.

She contained highly combustible gases and very little oxygen, so had to be flushed several times with fresh air before divers could begin the task of sealing the internal bulkheads.

The great depth meant that working shifts were short periods of less than four hours followed by long hours of decompression in the cramped chambers of the airlocks.

By 11th May 1936 everything was ready for the lift. Over the space of two hours she slowly inched upwards, then as the compressed air expanded and the mud loosened its grip she rushed to the surface in less than 30 seconds.

A day’s work followed on the surface to make further repairs to damaged bulkheads before she was towed to shallower water, and grounded. Her superstructure funnels and turrets were blasted away, then it was off to Lyness and later Rosyth.

1936 – Friedrich der Grosse

In June 1936, work started on the battleship Friedrich der Grosse, the flagship of the High Seas Fleet. Von Reuter had ensured that exceptionally thorough measures were taken when she was scuttled.

Upside down with a heavy list in 140 feet (43 metres) of water, she was tackled with the usual procedure. The first of 10 airlocks was fitted in July 1936, and the last before the end of the year. They were 80 to 100 feet (22 to 30 metres) in length. The use of 10 extra airlocks meant that the ship could be subdivided into more compartments to give greater control when she was raised.

Once inside the divers discovered that every valve in the ship was open, with valve spindles sawn off so that they could not be closed. Watertight doors had been thrown overboard and the sealing clips sawn off.

By April 1937 the bulkheads were airtight and the lift began on April 28th. Once again a slow inching upwards gave way to an eruptive rush. She was towed to shallower water where her superstructure was blasted away, then ten days later arrived at Lyness.

Three Dutch tugs and Metal Industries own salvage tug later took her to Rosyth. The journey was beset by problems from wind and tide, and it took 12 days before she finally arrived in Rosyth on 5th August 1937.

1937 – Grosser Kurfürst

Raising ships had become such a routine matter that when the battleship Grosser Kurfürst was raised on 29th April 1938, there almost no publicity given to the event. The lift proceeded smoothly with no problems.

(Scrap metal from Grosser Kurfürst was used to forge several of the plates in the liner Queen Mary.)

1939 – Derrflinger

The last of the ships to be raised was the battlecruiser Derrflinger. She lay deep in mud in very deep water with 90 feet (27 metres) of water over one side and 110 feet (34 metres) over the other.

Nine airlocks were required, the longest was 130 feet (40 metres) long and weighed 30 tons. Work began in July 1938, and she was divided into 11 sealed sections.

In July 1939 she was successfully raised to the surface, towed behind Risa Island, and anchored with ten seven-and-a-half ton anchors.

Video clip of the raising of Derrfliger

And there she remained for the next seven years, with a maintenance crew living in a hut on her upturned hull keeping her stable. World War II had broken out, so Rosyth was not available.

During the war, Metal Industries were allocated Admiralty salvage work round the north coast of Scotland. At the end of the war, Rosyth was still not available, so Metal Industries bought an Admiralty-surplus 40-year old floating dock, and used it to break up Derflinger at Faslane in the River Clyde.

Derrflinger was the last of the German ships to be raised. The battleships Kronprinz Wilhelm, Markgraf and König and the light cruisers Cöln, Karlsruhe, Dresden and Brummer were all lying in deep water beyond economic recovery so were abandoned to their fate.

1950s – demand for low-radioactivity steel

However events at the end of World War II changed the value of the steel on the sunken ships. The atomic bombs dropped on Japan and subsequent H-bomb tests increased the background radiation levels in the atmosphere. Steel making requires large quantities of air, and all steel produced after 1945 has a low level of radioactivity.

Thick steel plate manufactured before 1945 increased in value as it was needed for the shielding of sensitive radioactivity detectors in medical scanners.

The company Nundy (Marine metals) Ltd acquired the remaining hulks from the Admiralty. The owner, Mr Arthur Nundy did not intend to raise the ships, instead he used divers to place explosive charges on the ships and then return to the surface. This minimised their working time at high pressures. The ships were blown open, divers descended again, and attach slings to the large chunks of metal which were hauled to the surface.

As soon as the work became unprofitable, Nundy ceased operations leaving the hulks on the sea-bed, where they have become popular dive sites.

Rest in Peace

In October 2018, a Historic Scotland poll found that 90% of participants felt that the ships should remain subject to a “look, don’t touch” policy.