The emigrant girls: two daughters of Queensferry left this detailed account of their journey to the other side of the world.

| < Life and death on the Firth | Δ Index |

By 1847 my great-great-grandfather’s house must have been bursting at the seams, as was North Queensferry itself, and the two eldest girls decided to emigrate to Australia as domestic servants.

Through most of the 1800s and even up to 1950 the British government covered most of the cost for ‘assisted immigrants’ to go to Australia. In the 1800s there was a need to reduce the population in the towns and cities of England and provide labour in Australia.

Assisted immigrants had to have some skill, usually in agricultural labour, shepherding, blacksmithing, or domestic service. The ‘habitual poor’ were not allowed. Emigrants paid from £2 to £6 per person for the four-month voyage on chartered ships. Unassisted immigrants paid their own cabin class or steerage fare. During the 1850s and 1860s these were often gold seekers or wealthy merchants who sought to take advantage of the booming economy.

On January 8, 1848, Christina and Margaret left North Queensferry for the last time. Railways were still being developed so their father James and their brothers took them across the Firth for the steamer from Granton Pier to London, this service being provided by the Australian Commissioners for Emigrants and reflecting the number of Scots who made this long journey.

Advert for the Granton to London steamship

Advert for the Granton to London steamship

The girls boarded the barque William Stewart at Gravesend, east of London, whence she sailed to pick up more emigrants at Plymouth, setting sail on January 25 for a voyage round the Cape which would take 111 days. The Suez Canal did not open until 1869. Like most sailing ships, the William Stewart used prevailing westerly winds to reach Australia, winds which would take her east across the Pacific to sail around the world and return to England a year later. St. Helena in the South Atlantic was one of the busiest ports in the world as the ships put in for water and victuals.

A typical barque on the Britain to Australia route

A typical barque on the Britain to Australia route

Conditions would have been appalling by today’s standards, each traveller remaining in little more than a bunk for months, with a short trip on deck most days provided it was not stormy. Sanitation was a couple of buckets. In the tropics those between decks must have sweltered, as a sailing ship goes with the wind and there can be no through draught.

However, for its time the voyage was a good one and Christina and Margaret appear very happy in a letter which has become a classic account of an emigrant voyage.

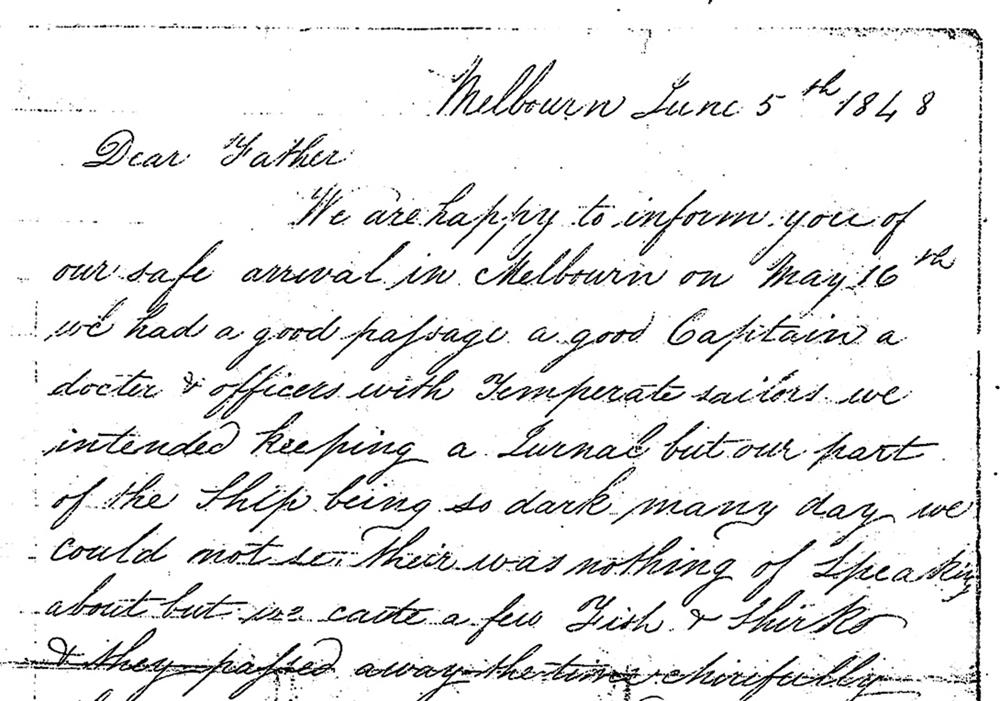

Melbourn June 5th 1848

Dear Father

We are happy to inform you of our safe arrival in Melbourn on May 16th. We had a good passage, a good Captain, a doctor and officers with temperate sailors. We intended keeping a journal but our part of the ship being so dark many day we could not see. Their was nothing of speaking about but we caught a few fish and sharks and they played away the time cheerfully. There was some children died but none of the old people died. It would have been a great deal worse if there had been but the children were never much minded. There was eight births no marriages on board but there was two of the children baptised named Eliza and William Stewart.

Dear Father be shure and let us know the name of our last sister that was born before we left home. I hope you received our letter from Pleamouth and we dropt one by the way. We had Church on board every Sunday weather permitting. We never wanted a meal of vitals all our passage so you may thank the Lord for our safe arrival. There was 51 single women all in our room and we were very happy. There was but 16 English and 35 Scottish were all engaged on board but ourselves. It was like a Fair. We went to whom we had our letter to and they found situations for us and we got more wages than was given on board. We have good situations and we are getting £25 per year.

The house maids have no grates to clean. They all burn wood. There is not such a thing as a grate to be seen. The work is not so hard as it is at home nor the mistresses are not so sassy. They are glad to get any person to work to them. Melbourn(e) is as large a place as Dunfermline. The most of the houses are brick. It is wonderful to see such a place only to be 13 years old.

It is all Bush round thousands of miles what we call a plantation at home. The natives live there and large Sheep Stations and Bolix [Bullocks!] Stations there and the natives live like the soldiers. They occupy so much ground and they have Kings and Chiefs and any of the rest of them goes on one another’s ground they fight with them. The beef is 2d per pound, rice 6d per pound. Bread cheap. Barley 6d per pound. Clothing and drink very high. There is no beggars here. Rich and poor lives all alike. If people is willing to work they can get plenty to do. The people is great Tea drinkers, the tea is 1/6 per pound. They have it after every meal.

The weather has been very bad since we arrive and the streets is not for females to walk. They are in such a state they will not let us out. They bring everything to us that we want. The people are so kind that we are quite ashamed of their kindness to us and as for Mr and Mrs Brown they are awful kind to us and always to make their house our home at any time. Be sure and tell Mr William Brown and the family that they are both well. They have three nice children and let him know how much obliged we are to him for his letter. With our kind love to grandmother and all friends and acquaintances. …….

None need to be afraid to come here but for the passage for it is long, it is upwards of twenty thousand miles. We have never seen any person that we knew as yet. Dear Father be shure and write and let us know how you are all at home. The money that we received from you that we never needed any of it so we put it in the Bank and if you want any money be sure and let us know and we will remit it by a Bank order.”

The rest of the letter is missing. The original is in the State Library of Victoria, MS.10233.

The letter refers to meeting the Brown family in Melbourne. The Browns were another seafaring family in the 1841 North Queensferry census. It seems that the Mr and Mrs Brown mentioned had already emigrated, and perhaps their favourable report induced the sisters to choose Australia rather than the much shorter journey to America. But one significant occurrence is not mentioned in the girls’ letter.

From the Port Phillip Herald, Tuesday 15 May 1848:

Arrived the ‘William Stewart’, a barque of 576 tons and said to be a fine vessel, British built of oak, the Captain being William Jamison. Passengers – Mr Charles Horrell, Mr W. H. Goddard, and 234 bounty immigrants, comprising 54 single females, 47 single males, and married couples with their families.

Mr. W. H. Goddard was a merchant from Surrey and paid his own passage. Perhaps his eye was caught by a pretty Scots lassie on her daily outing on deck, perhaps they met on the 600-mile voyage from Melbourne to Adelaide, for as yet Australia had no railways. On November 10, 1848, Margaret McRitchie aged 22 and William Henry Goddard aged 26 were married in Holy Trinity Church, Adelaide. They had two children and the family became prosperous. William died in 1868 at the age of only 48, and Margaret died in 1912 at the age of 83.

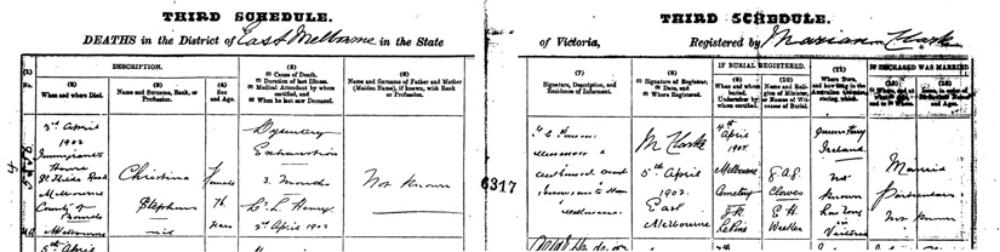

For Christina, life was to be very different. The South Australian Register for June 11, 1856, reported the wedding ‘at the residence of W. H. Goddard, Hindley Street, by the Rev. John Gardner, of Mr William G. Stephens, Geelong to Christina, eldest daughter of James McRitchie, Esq, shipowner, Queensferry, Fifeshire, Scotland.” The couple had four children.

The 1860s were the time of the gold rush. In 1851 the population of Victoria was about 80,000 and 10 years later it was more than 500,000. Men were arriving from all over the world, and contemporary accounts mention widespread desertion of wives and families as civil servants, ships’ crews and even policemen headed for the goldfields.

After the birth of her last child we lost trace of Christina and her husband William George Stephens. But long after we thought this story was complete, Cynthia Foley contacted us from Australia. She is the great-granddaughter of William George Stephens, and told us that his real name was Stephen William Goetze, born in London, and he had been married twice previously.

As Stephens, he had arrived in Adelaide in September 1849 as a crewman on the barque Louisa Baillie, which had sailed from Plymouth in April. Nothing is known about him until 1856 when he married Christina. It seems he did desert Christina and about 1873 he met Hannah Ada Sylvia Phillips of Manly and had two sons by her. The couple were married on December 19, 1878, in Sydney, Stephens declaring that he was a widower.

Did Christina become estranged from her family? We shall never know. No detailed census records exist and we searched directories and hospital registers but there is no trace of her in the 34 years from 1864.

On April 3, 1902, Christina Stephens formerly McRitchie, aged 76 yrs, died alone in the Immigrants Hostel, Melbourne, the last refuge of the destitute. Far from the green slopes of the Firth, she rests in the unmarked pauper’s grave K470 in Melbourne General Cemetery, the grass above her burned brown by the fierce Australian sun.

| < Life and death on the Firth | Δ Index |