Daily life in North Ferrie: a self-contained community dominated by the Church

| < Life as a Ferryman | Δ Index | Life and death on the Firth > |

It is difficult to say whether life in North Queensferry was any harder than in other Scottish villages. The Firth of Forth was frozen over in the great freeze of 1608, the plague hit Dunfermline and Lothian in 1609, and the Great Dearth between 1645 and 1715 is now known as the Little Ice Age when northern Europe suffered short summers and savage winters in which rivers and even the sea froze solid.

Scotland was particularly hard hit, with poor harvests in the cold short summers leading to famine and migration to the (slightly) warmer lowlands. In January 1740, Dunfermline was visited by terrible storms of snow, and where it drifted it was at least 24 feet deep. The potato blight which so terribly affected Ireland in 1845–1847 struck Scotland as well, though the Scots were not as dependent on one crop.

Fresh water was a valuable commodity as there was only one well and water had to be conserved. Today, inset into the wall behind the old village pump is a cast iron door which depicts an arguing sailor and fishwife. Cattlemen and sailors needed fresh water and the fishwives readily used their gutting knives to protect their water supply. But the village was spared wars and rebellions, and the terrible Clearances of their Highland homeland.

Our ancestors would have climbed the steep Brae twice daily on Sundays on their way to church in Inverkeithing, more than a mile away. The old school (centre) faces down the Brae. The laigh houses ‘at or near the foot of the Brae’ sold by James’s widow Helen Main McRitchie in 1767 probably stood on the site of the War Memorial and garden on the left. The village well is on the right.

Our ancestors would have climbed the steep Brae twice daily on Sundays on their way to church in Inverkeithing, more than a mile away. The old school (centre) faces down the Brae. The laigh houses ‘at or near the foot of the Brae’ sold by James’s widow Helen Main McRitchie in 1767 probably stood on the site of the War Memorial and garden on the left. The village well is on the right.

The villagers’ diet would include cereals which they grew themselves, fish in large quantities, meat for special occasions, and perhaps gugas, gannet chicks from the Bass Rock in the mouth of the Forth. Gugas is still a delicacy in the Western Isles and the islanders harvest an agreed number each year. The gugas leg, complete with webbed foot, is reserved for honoured visitors and our Isle of Lewis friends describe the flavour as turkey roasted in fish oil.

The Church dominated most aspects of the community, providing moral guidance and social service. Indeed North Queensferry must have been a pretty gloomy place, for the Rev. Andrew Robertson wrote in his 1836 Report that there was a rigorous discipline within Inverkeithing Parish.

Between 1700 and 1730 there were instances of persons rebuked before the congregation for swearing, drunkenness, stealing, for not attending public worship, for being out of doors unnecessarily, or carrying water on the Sabbath, for ferrying people across on the Sabbath without an order from the minister, for abusive language or calling names, very frequently women for scolding, once, a man for cursing and striking his wife, and another for “consulting a wizard”.

In Scots law it was sufficient for a couple to declare before witnesses that they took each other as husband and wife for the marriage to be legal, a practice which continued until 1939. The Church was opposed to such unions, not only because of the loss of revenue from fees. No record of the transaction was normally made, the marriage could later be denied, and there were no social benefit payments in those days.

Many a young mother was left with no income when the father denied the union. If the man was in the army or navy he might be killed or drowned, and if the marriage was irregular the wife was not informed of her husband’s death and might hear of it only by chance. Unable to prove her marriage, she did not qualify for a widow’s pension, and could not even claim a place on the poor roll.

Clandestine marriage was generally discovered when the first child was born and the parents sought baptism. They came to the Kirk Session, confessed their fault, and were, ‘rebuked, exhorted, and ordered to pay the charges’. The fines went to the poor box, the normal fees for a regular marriage were paid, the marriage was regularised, the baby was baptised and all parties were happy.

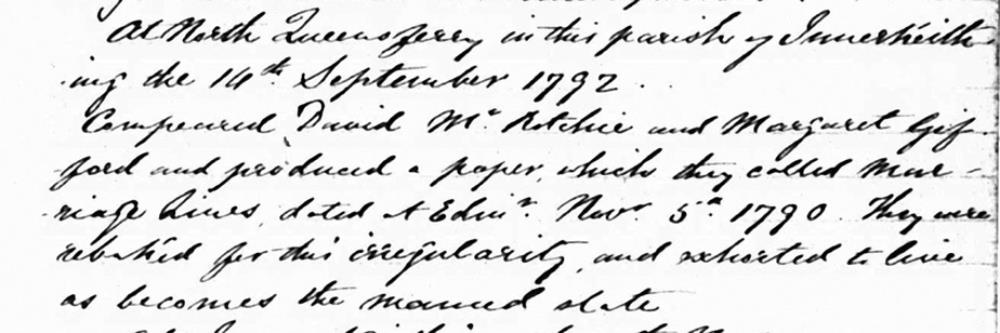

From the Inverkeithing Kirk Session records:

“At North Queensferry in this Parish of Inverkeithing, the 14th September 1792. Compeared [old legal term meaning summonsed] David McRitchie and Margaret Gifford and produced a paper, which they called marriage lines, dated at Edinburgh November 3, 1790. They were rebuked for this irregularity and exhorted to live as becomes the married state.”

The marriage ceremony was usually in the bride’s home. Church weddings were not encouraged because a wedding often led to a party, and Scots Presbyterians were not keen on happy faces, still less dancing, in the place of worship.

Keeping up with relationships must have been difficult in such a small and confined community. In 1800 the village had at least six David McRitchies and six James, one of them female, as was the practice to maintain family names when a male child died early. Marriages of first cousins were not uncommon. For example, David McRitchie, mariner, and Jean McRitchie, were married in 1812; we thought this was a comfort marriage between elderly in-laws until finding the arrival of baby James in 1813.

Then we found the marriage in 1868 of our great-great-great uncle David McRitchie, shipwright, to his cousin Jane McRitchie. Today’s family members are adamant that living with one McRitchie can be difficult enough, but two under one roof . . .

| < Life as a Ferryman | Δ Index | Life and death on the Firth > |