From bustling port to quiet village: centuries of ferry tales.

| < Intro | Δ Index | Life as a Ferryman > |

Joining the visitors wandering around the sleepy village of North Queensferry today, its houses and cottages beautifully restored and maintained, it is difficult to imagine how busy it must have been two centuries ago when my forefathers were among the families who operated the historic Queensferry Passage.

The narrow streets would have been packed with coaches coming and going, travellers entering and leaving the village’s 17 inns and hostelries, bellowing cattle being driven to the ferries, farmers shovelling their droppings into carts to manure their fields, tradesmen offering their wares, and boatmen touting for business.

By the 1860s North Queensferry had 17 inns where travellers could overnight before the next day’s sailings, as there were no regular services by night or on Sundays. Among those inns and lodgings were several owned by my great-great-grandfather James … but let’s start at the beginning.

My family originated 60 miles north in Glenshee, the A93 route from the Forth to Upper Deeside through Scotland’s highest mountain pass. Surnames of Scotland (Black) p562 records that Robert McRichie or Makryche ‘of Dalmunzie’ and ‘in Glenshee’ appears in 1571-83-84-89 and his son Duncan McCreiche in Glenshee in 1564. Over the next century they moved south.

The first McRitchie marriage in Fife was recorded on May 14, 1650, and for more than 200 years my direct ancestors joined other Gaelic-speaking families such as Anderson, Bell, Brown, Buchanan, Johnston, Penney, Scotland, Turnbull, and Wilson in the unique co-operative of North Ferrie, where everyone had equal shares, limiting its size to about 200 souls.

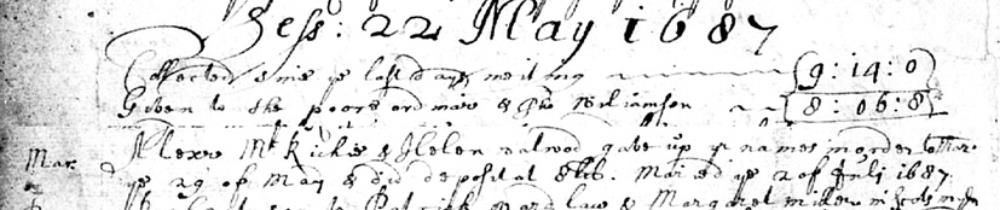

From the Inverkeithing Parish Register, May 22, 1687: Beneath the church accounts and donations to the poor, “Alexr.McRichie and Helen Walwood gave up their names in order to marry ye 9 of March and did so marry ye 12 of July 1687.

From the Inverkeithing Parish Register, May 22, 1687: Beneath the church accounts and donations to the poor, “Alexr.McRichie and Helen Walwood gave up their names in order to marry ye 9 of March and did so marry ye 12 of July 1687.

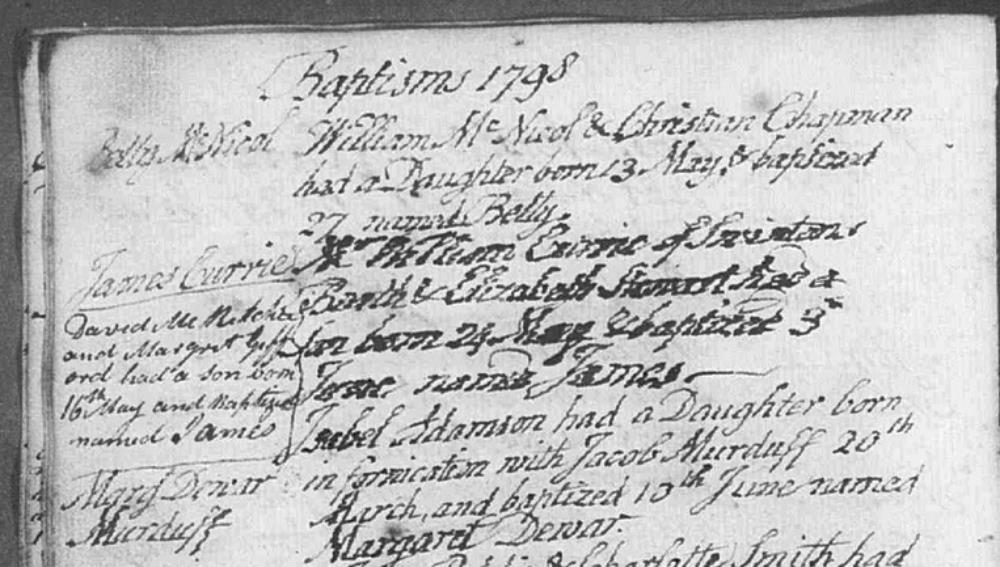

Great-great-grandfather James makes his debut in the margin of the Parish Register, 1798. Perhaps father David was late with the baptism fee. Note the following entry for Isabel and Jacob.,/p>

Great-great-grandfather James makes his debut in the margin of the Parish Register, 1798. Perhaps father David was late with the baptism fee. Note the following entry for Isabel and Jacob.,/p>

From History of Dunfermline, by Andrew Mercer (1828):

“The Reformation, the effects of which were so signally displayed in Dunfermline in the destruction of the Abbey, made no change in the faith of their neighbours, the boatmen of North Queensferry who formed a cooperative in which all were equal, which could be joined only by eldest sons born in the village, and which survived while the storms of Scottish history raged around them. As vassals of the monks they continued to adhere to the ancient religion; the rites of which were administered in the chapel founded by Robert Bruce.”

“On Cromwell’s army landing in Fife, they were astonished to find a Roman Catholic chapel there; which they furiously assailed, and left not one stone upon another. The inhabitants converted the area of the chapel into a burying ground, which is still used in this manner. They are now good Protestants, and have a gallery in Inverkeithing church, erected at their own expense”.

St John’s church in Inverkeithing was converted from a barn in 1752. The gallery was later erected by the boating families including the McRitchies.

St John’s church in Inverkeithing was converted from a barn in 1752. The gallery was later erected by the boating families including the McRitchies.

Mercer recorded that in early days the boatmen lived in a little square of cottages on the margin of what was once the Ferry Loch, on the top of the Ferry Hills. “The inhabitants of North Queensferry uniformly consisted, from time immemorial, of operative boatmen without any admixture of strangers. Only those born below the Ferry Hills could become boatmen.”

Every Saturday evening the week’s earnings were divided into shares, called deals. ”One full deal was allocated to every man of mature age who had laboured during that week as a boatman, whether he acted as master or mariner, or in a great boat, or in a yawl. Next the aged boatmen, who had become unfit for labour, received half a deal, or half the sum allocated to an acting boatman. Boys employed on the boats received shares proportioned to their age, from one shilling and sixpence up to a full deal. A small sum was also set aside for a schoolmaster, and for the widows of decayed boatmen.”

Mercer records that nobody became a boatman unless by succession, a right limited to the first generation. The children of those who had emigrated, and were born elsewhere, had no connection with the Ferry; but if the son of a boatman found himself unfortunate in the world, he was always entitled to return, to enter into one of the boats, and to share in the community in which he was born.

“That community has always consisted of nearly the same number of persons. The whole community, including these and the old men and boys, and the women of every age, amounted to about two hundred individuals. It was kept down to this number by emigration.

“The community has, accordingly, existed for ages destitute of riches; but none of its members has been reduced to absolute poverty because, by the laws of their society, the men of mature age had always laboured for the past and the future generations, and had divided with them the bread which they earned.”

| < Intro | Δ Index | Life as a Ferryman > |