Oil

| < The Stevensons | Δ Index | Beating the Chill > |

The Northern Lighthouse Board experimented with other sources of light before settling on oil lamps.

Coal was an early contender – as used on the Isle of May until 1815. Coal gas was also tested, but was difficult to transport to remote locations, and carried the risk of explosion in the event of leaks from pipes or containers.

Electricity was tried– in the form of an arc-lamp created by passing a current through two carbon electrodes which are then drawn apart, resulting in a brilliant arc of light. (This can be seen – through suitably darkened glass – in the modern process of arc welding.)

The problem with this technique is that once the arc has been “struck” the distance between the electrodes has to be carefully maintained – tricky at the top of a remote lighthouse! In addition, electricity had to be generated on-site using a steam engine or later an internal combustion engine to drive the generator – both needed a source of fuel.

Finally, limelight was tried. A ball of lime, about 9mm in diameter is heated with an oxy-hydrogen flame. The lime becomes incandescent, and generates a bright white light. This is the same as seen in an incandescent gas mantle.

[It is believed that a variation on this technique, using an oxy acetylene flame was installed in the North Queensferry light tower in the early 20th century. Acetylene gas was generated on the far side of the pier (adjacent to Mount Hooly) and piped into the tower. A small section of gas pipe is visible from the stair case.]

Types of Oil

Having settled on oil lamps, there was still the matter of what oil to use.

In the early 1800’s the only sources of oil were plants and animals.

Mineral Oil, in the form of paraffin (kerosene) was first produced by James Young in 1850.

In 1848, while working in the mining industry, Young noticed that oil was leaking from the ceiling of a coal mine. He deduced that there must be a way of extracting oil from coal. He patented the process of heating coal to extract oil in 1850, and set up the first commercial producing oil refinery in the world near Bathgate.

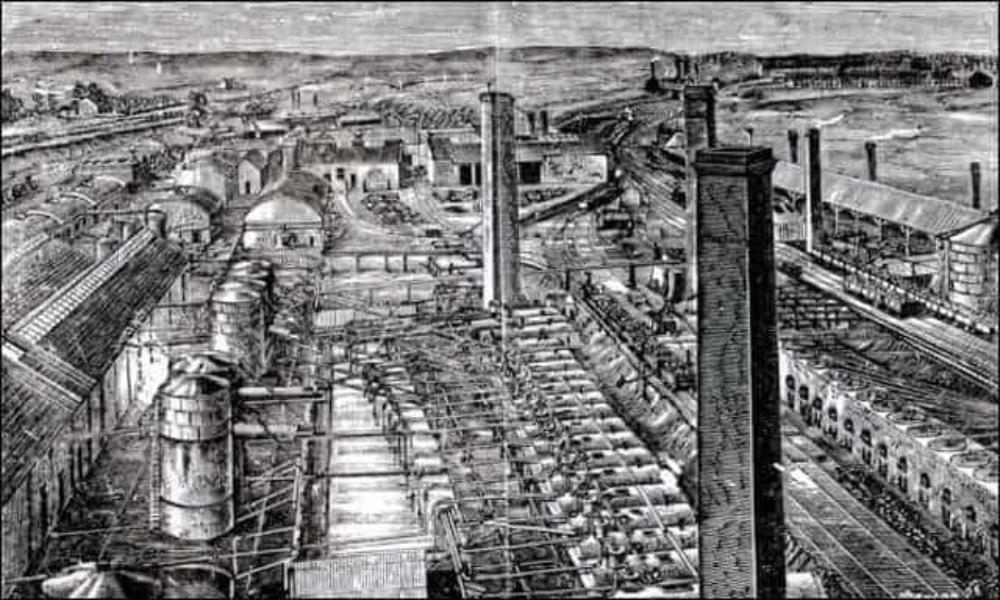

James (Paraffin) Young’s Oil refinery at Addiewell, West Lothian

James (Paraffin) Young’s Oil refinery at Addiewell, West Lothian

Young distilled crude oil from locally mined shale and turned this paraffin, and other useful chemicals. This why he was nicknamed “Paraffin Young.”

The evidence of Young’s processes survives today, in the form of ‘bings’ in West Lothian These red heaps some 30 to 90 metres high are the mineral waste from the shale mining and distillation process. They are a reminder that for a few years in the 1850s, Scotland was the biggest producer of oil in the world!

However in 1810, the only sources of high quality oil were Whale Oil Olive Oil and Colza (Rapeseed) Oil.

Whale Oil had been the traditional choice for lighthouse lamps, but when a variety of rapeseed suited to the British climate was introduced, Colza Oil proved to be better.

An 1847 House of Commons report stated that it produced the same light output as Whale Oil at half the price, and remained fluid at low temperatures, avoiding the need for a frost lamp. (As note earlier, seal oil was used in Canada.)

The only drawback was that it is more viscous than whale oil, so requires a thicker wick, and hence a change to the burners in the Argand lamps.

Here is a copy of Robert Stevenson’s 1864 Report on the Quality of the Oil

| < The Stevensons | Δ Index | Beating the Chill > |