First Air Raid of WWII – 42

Criticism of the defences

| < 41 Fate of the German prisoners | Δ Index | 43 Arrival of Barrage Balloons > |

As a legacy of London’s vulnerability to aerial bombardment during WWI many pundits, including H.G. Wells, prophesied that British cities would be pulverised from the air by an intensive bombing campaign. And, following the raid of 16 October when the euphoria subsided, in its place began the recriminations.

The main bone of contention was the fact that whilst air raid warnings had been sounded in military establishments only after the raid had begun, no air raid warning had been sounded in the city itself.

The Edinburgh Evening News published an article which alleged that whilst the capital had not warned its people of the impending air raid, the sirens in Perth and some districts of Fife had been sounded. This article fanned the flames of discontent.

In actual fact the military bases had quite naturally gone on alert as soon as the air raid began and these sirens had prompted the civilians living nearby to make their way to the nearest shelter. The local siren at Port Edgar had sounded three minutes after the first bombs had fallen, but only after the siren at Rosyth had been clearly heard from across the river. This was followed by the sounding of the works hooter at the South Queensferry Distillery.

At South Queensferry, where the sirens did provide warning of the air raid, many chose to remain outside in order to watch the action overhead. The citizens of Edinburgh only became aware that an air raid was in progress and not a practice exercise when the AA guns opened fire to the north followed by the spectacle of Spitfires pursuing bombers overhead.

Except for those in military establishments, no sirens were sounded in Edinburgh that afternoon and it was that point which became the target for criticism. The concern expressed by the lack of adequate warning in some areas prompted the Lord Provost, Henry Steele, to state that be was ‘very annoyed’ and determined to get to the bottom of the matter. His reaction may have been attributable in part to the fact that his own house had been raked with gunfire. He was yet to discover that it was .303 calibre and not 7.92mm!

Following the raid a report was sent from the police station at South Queensferry to the Chief Constable at Linlithgow:

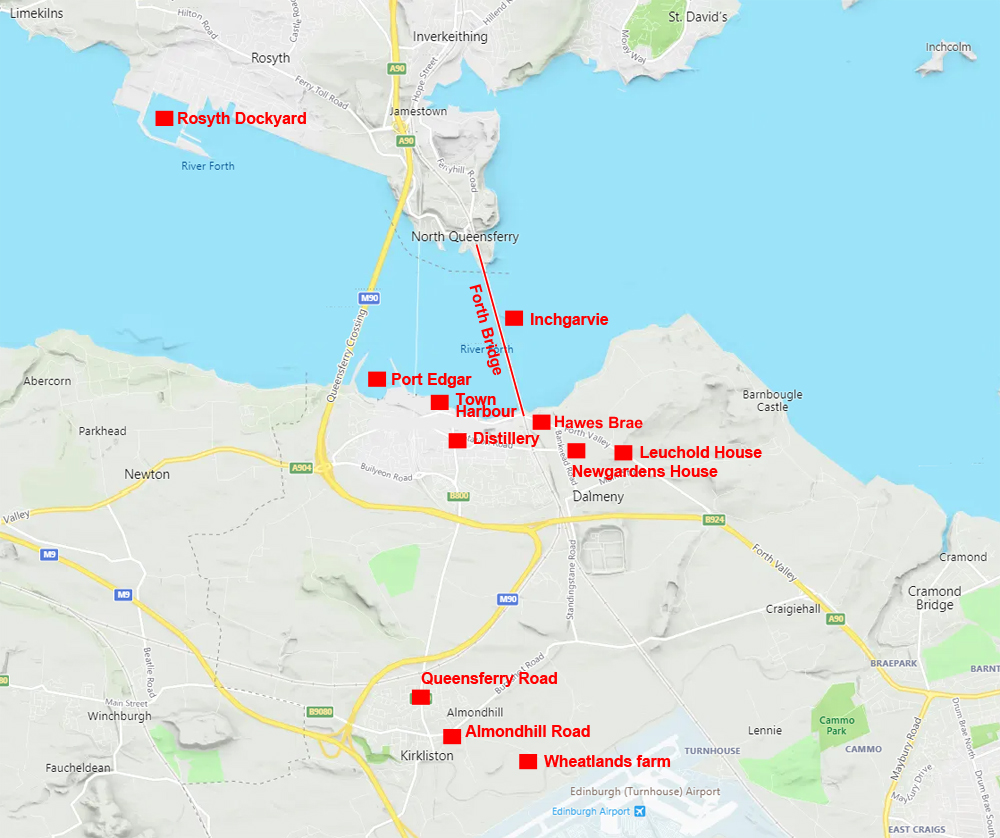

I beg to report that an Enemy Air Raid commenced about 2.30 p.m. on this date over the Firth of Forth in the vicinity of the Forth Bridge, where H.M.S. Edinburgh and H.M.S. Southampton were at anchor a short distance east of the Bridge and south of Inchgarvie Island.

Four attacks were made on the warships by three enemy aeroplanes, ten or twelve bombs being dropped between the ships and the Forth Bridge. Two small boats tied to H.M.S. Edinburgh were damaged and sunk and so far as is known there was one casualty on that ship, a naval rating being seriously wounded.

No bombs dropped on land, at least within this county, but shrapnel fell at the Town Harbour, South Queensferry (in the sea), on Hawes Brae and at Newgardens House, Dalmeny.

Shrapnel also fell at the house occupied by David Drummond, Water Superintendant, Queensferry Road, Kirkliston, and Peter McGowan, (24), farmer of Wheatlands Farm, Kirkliston was slightly wounded on the back by shrapnel while working in a field on that farm.

No Air Raid Warning Messages were received and the first intimation of the Air Raid was machine gun fire from an aeroplane followed by the explosion of a bomb being dropped in the vicinity of the Forth Bridge. The siren at Port Edgar then sounded, followed by the local signal on the Distillery siren, and bomb explosions and the noise of anti-aircraft gun fire from the local units.

What is believed to be the ‘tail’ of an enemy plane [actually the rear canopy of Pohle’s aircraft] fell east of the Forth Bridge into the water, floated north-westwards and was later picked up by a picket-boat from Rosyth along with other small pieces of wreckage.

The actual raid in the first place would last about 50 or 60 minutes, and about 3.50 p.m. the ‘Raiders Passed’ signal was sounded at Port Edgar, followed by the same signal on the local siren. About 4 p.m., however, the signals sounded the’ Air Raid Warnings’ and a plane was sighted over Port Edgar but was driven off by Anti-Aircraft Gun fire from the surrounding batteries and the two warships.

It has now been ascertained that a 2lb, anti-aircraft cartridge was picked up, unexploded, in the drive about 400 yards cast of Otter, and two anti-aircraft shells were found, also unexploded, at Kirkliston, one on Almondhill Road and the other on the street at the crossroads in the village. These shells have been attended to by Inspr. Duncan, Linlithgow.

Some slight damage was done in KirkIiston, one pane of glass in a window at 9 Queensferry Road, occupied by Mrs Jane Hood or Robertson being broken by part of a nose cap and several telephone wires are down in the district. All this slight damage is believed to have been caused by the shrapnel from anti-aircraft fire.

Fortunately at the time of the raid, few people were on the streets and the police succeeded in getting them under cover very quickly. There was little or no panic and the public in the district behaved very well.

The final ‘Raiders Passed’ signal was sounded about 4.35 p.m. on the Port Edgar siren, followed by the local signal here. There was no air raid message received by telephone at Port Edgar and they sounded all signals on bearing the Rosyth siren.

There were other reports of shrapnel raining down over a wide area.

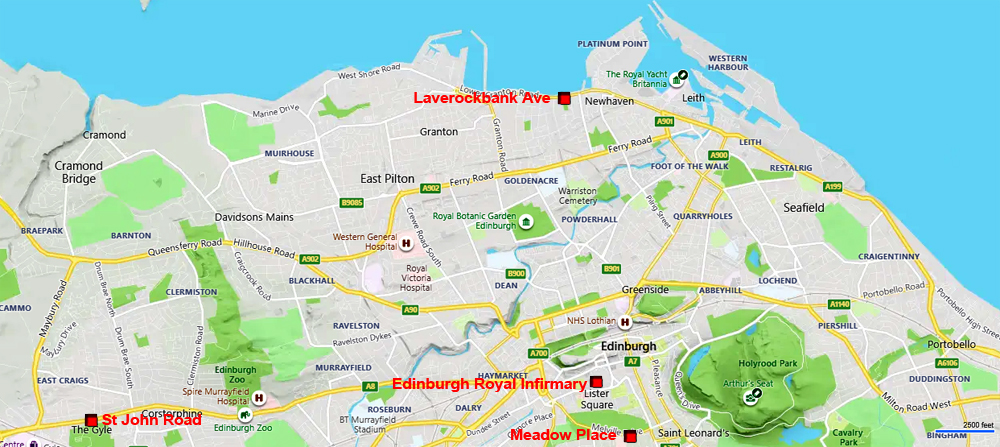

Traffic held up by police on the Hawes Brae (South Queensferry) was peppered and windows were broken in Inverkeithing, South Queensferry, Kirkliston, Granton and Portobello where one piece smashed through the window of a moving tram, narrowly missing a passenger. Territorials guarding the north end of the rail bridge had to duck behind the parapet as HMS Repulse added her considerable barrage to the fray, sending streams of lead whistling over their heads.

A dog hit by splinters in Alma Street, Inverkeithing had to be destroyed and a woman standing at Dalmeny Station escaped injury when a red-hot shell splinter dropped into the pocket of her apron, setting it on fire. Several telephone wires were cut around South Queensferry and 24-year-old Peter McGowan was slightly wounded in the back while working at Wheatlands Farm, Kirkliston. One large piece of shrapnel fell through the roof of the scullery at Couston Farm, Aberdour, slightly injuring the farmer’s wife Mrs Milne.

The fusing of shells in the early days of the war was a somewhat haphazard science and many dropped back to earth without exploding. They were found at Leuchold House in Dalmeny Park, on Almondhill Road and at the crossroads in Kirkliston.

Another shell caused much concern when it was heard whizzing over Linlithgow to explode in a wood south of the town.

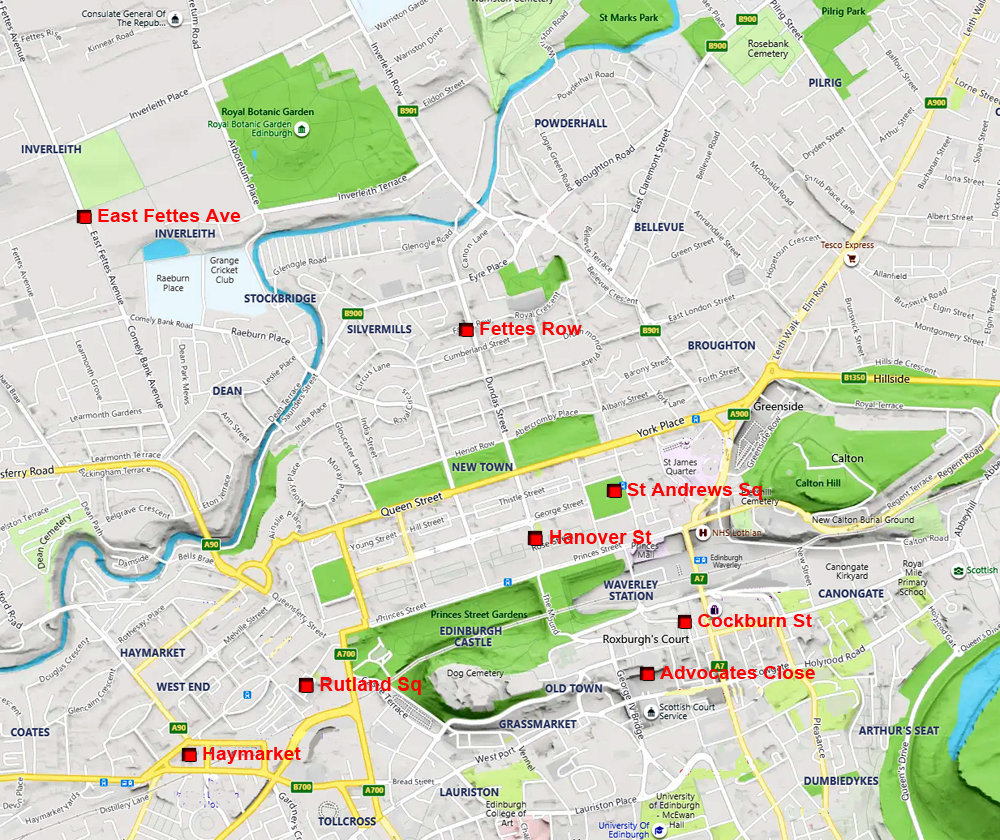

In the city considerable quantities of shrapnel fell around Haymarket, in Rutland Square, Hanover Street, Fettes Row, St Andrew Square, Advocate’s Close, Cockburn Street, East Fettes Avenue and Corstorphine, where the roof of the Home and Colonial Stores in St John’s Road was damaged.

Potentially lethal shell caps made of brass and lead were also crashing to earth. One landed only inches from a nursing sister at Edinburgh Royal Infirmary and another went through the roof of a laundry at Meadow Place.

Yet another damaged a concrete path in the front garden at 24 Laverockbank Avenue, Trinity, and was still hot when handed to a passing policeman some minutes later. With commendable phlegm, Mrs Kenny asked him, ‘Is this something they have left behind?’

In the House of Commons the following day, Prime Minister Chamberlain answered the question as to why there had not been an air raid warning in the Scottish capital:

As the attack was local and appeared to be developing only on a small scale, and as our defences were fully ready, it was not considered appropriate in this particular instance to issue an air raid warning, which would have caused dislocation and inconvenience over a wide area. The responsibility for issuing air raid warnings must be left to the competent authorities, but the circumstances in which warnings had been issued would be carefully reviewed in the light of the experience gained.

The press were unhappy with the PM’s explanation regarding the absence of warnings. The Scotsman wrote:

The truth is that the competent authority was extraordinarily fortunate over Monday’s experience, and only the lucky fact that there was no loss of civilian life … What would have been done to the competent authority if, for example, a bomb had been dropped on a train passing over the Forth Bridge, as might have happened? If it is wise, the competent authority will not cease to bless its good fortune, and take the escape to heart.

On the subject of air raid sirens the paper wrote:

An amazing feature of the attack was that many places, including Edinburgh, sounded no air raid sirens, and people stood in the streets gazing up at aerial dogfights, unaware that it was the real thing. Even officers of the defence forces were for a time under the impression that all the planes were British. One explanation of the absence of warning was that earlier there had been British bombing practice on the Forth.

Also unhappy with the PM ‘s response, following a meeting with the Edinburgh ARP Committee, Lord Provost Henry Steele waded in with his own comments: ‘It was apparently the feeling of the Committee, however, that the matter could safely be left where the responsibility lay – namely, the Air Ministry and the Edinburgh Fighter Command’ at Turnhouse. Fighter Command HQ itself was responsible for issuing air raid warnings. Air Chief Marshal Dowding was aware that a number of false alarms had caused confusion that day. Apparently, in view of this he had overruled the established procedures in favour of holding back for further confirmation that it was a genuine attack. This would explain why no one was actually instructed by the authorities to sound the sirens.

Every available aircraft in 602 and 603 Squadrons took to the air that afternoon in search of the enemy raiders. No blame can be levelled at the pilots if they were ordered to investigate sightings in one area when in fact the Germans were in another. Regardless of the fact that Drone Hill went off the air, the raiders were continually tracked by other RDF stations along the east coast until they passed overhead when Observer Corps correctly identified the aircraft and posts of 31 Group Galashiels and 36 Group Dunfermline tracked them inland. Sir Hugh Dowding was so pleased with the performance of the Observer Corps he sent a message of congratulations. Confusion lay with the reporting of sightings by other ‘observers’. These reports came from search-light and anti-aircraft batteries and ultimately Spitfires were sent up to intercept what were probably friendly aircraft.

Importantly, mistakes made on 16 October 1939, were noted and by the time the Battle of Britain occurred Dowding had an extremely effective and comprehensive early warning system at his disposal. Each aspect of the system had a vital part to play in the air battle against the Luftwaffe and Britain’s ultimate victory.

Whilst no civilian lives were lost as a result of the bombing on 16 October, later air raids by the Luftwaffe against Scottish targets claimed the lives of many civilians in Edinburgh and its suburbs.

| < 41 Fate of the German prisoners | Δ Index | 43 Arrival of Barrage Balloons > |