Early defences of North Queensferry

< Back to Military History of North Queensferry

Forth Defences

For centuries, there have been Military Sites along the Forth to guard against invaders and intruders.

The Fort and the Great Sconce

In the 1600’s the local defences included, “a battery of 16 cannon on Inchgarvie island plus the defences of North Queensferry itself – 12 cannon on the Ferry Hills, known as “The Great Sconce”, and 5 cannon in “the Fort”, with an armed guard-ship in the sheltered waters of St Margaret’s Hope.”

The 12 cannon on the Ferry Hills, known as “The Great Sconce” were probably close to the site of Carlingnose Battery, with a commanding view of the Queensferry Crossing, and an overlapping field of fire with the battery on Inchgarvie.

Several cannon were captured by Oliver Cromwell’s sea-borne invasion forces which landed around the peninsula on Wednesday 16th July 1651. Some of the guns were dragged to Gallow Bank, to protect Cromwell’s troops from the Scots Army approaching from the direction of Dunfermline. Cromwell’s troops dug-in on the Ferry Hills as more reinforcements arrived.

The Battle of Inverkeithing was fought on Sunday 20th July 1651 between Cromwell’s troops on the North side of the Ferry Hills and the Scots on the slopes of Muckle Hill and Whinney Hill. The initial engagements took place around Ferrytoll. The Scots were forced to withdraw to the north, resulting is a trail of slaughter all the way to Pitreavie.

It is recorded that Cromwell’s troops damaged some of the properties in the village, most notably St James’s Chapel. There are no visible remains from the time of battle but the whole peninsula can be considered as a military site from that time.

The Ness Batteries

A failed attack on Edinburgh from John Paul Jones’s American privateers in 1779 triggered the creation of a Gun Battery and then a Fort at Leith. These were completed in 1790.

More immediately, in North Queensferry the battery on the point of the East Ness was reinstated and a second battery was built on top of Castle Hill (later Battery Hill). There were about 20 guns in total between the two batteries – all 20 pounders.

The lower battery, known as ‘Ness Battery’ was located just above sea level at the point itself and appears to have been the main battery.

A plan of the Ness Battery in 1812 shows embrasures for nine guns, a Field Train Shed, Flag Staff and Master Gunner’s house.

Great Britain eventually recognized U.S. independence in the 1783 Treaty of Paris, however a war with France now seemed likely, so the batteries were retained with repair work carried out in 1793, 1795 and 1798.

On 3 March 1797, 32 boatmen and other inhabitants of North Queensferry wrote to the Lord Provost of Edinburgh, that, having been informed of the threat of a foreign invasion, they offered themselves in defence of the King, country and constitution, for service at the North Ferry Battery, Inchgarvie, or Inchcolm.

Their letter was forwarded to Lord Adam Gordon, Commander of the Forces, who duly wrote back accepting their offer which did ‘them much credit and will accordingly be acknowledged in the newspapers.’ Impressed by the selflessness of these men, Sir Walter Scott wrote to them, thanking them for their patriotic action in coming forward as volunteers for the defence of their country.

The Queensferry Volunteers were disbanded in 1802, after the Treaty of Amiens. However they reformed when war broke out again in 1803. Captain Ross received his commission on 25 June 1803 and formed the Royal Queensferry Artillery Volunteers to re-man the batteries at Battery Hill, Inchgarvie and Inchcolm. They were still active in 1812, and further repairs were carried out in 1814.

In 1817 the Board of Ordnance ordered that the batteries should be dismantled, although the guns remained on skids, and the battery grounds were retained with further repairs in 1823.

The property was eventually advertised to let in 1835 with the proviso that the government could re-occupy it: ‘The ordnance property of North Queensferry Battery consisting of a house and some pasture land, with a range of wooden sheds, which are not to be taken down, and will be let … on the understanding that the premises may be resumed at any time by government when required for the public service.’

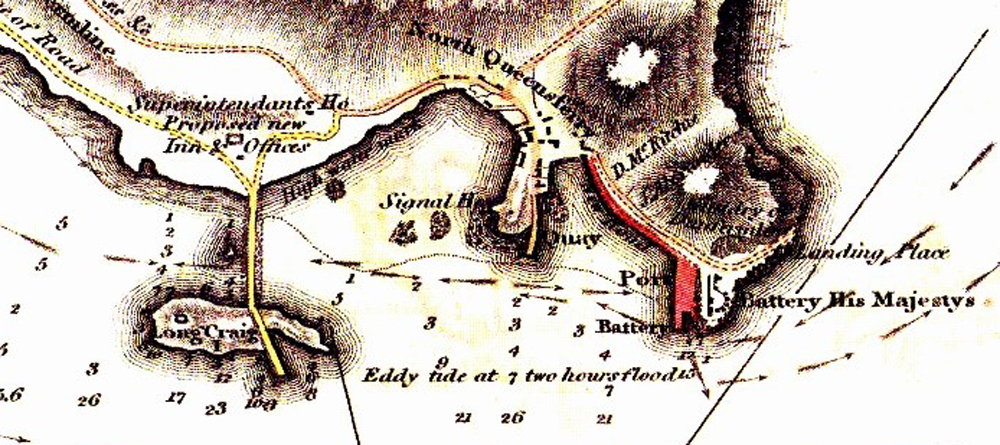

The Fort is shown in Rennie’s map of 1811 shows “Battery His Majestys” at the site of the future Forth Bridge foundations.

Extract from John Rennie’s map of 1811

Today, the caissons of the north section of the Forth Rail Bridge lie on the site, although some of the walling in the area may date from the battery’s life.