Rosyth Dockyard 9 – 1912-1913 The Main Basin Sea Walls

| < 8 – 1910–1911 The North Wall of the Inner Basin and Graving (Dry) Docks | Δ Index | 10 – 1914 Construction progress at the outbreak of war > |

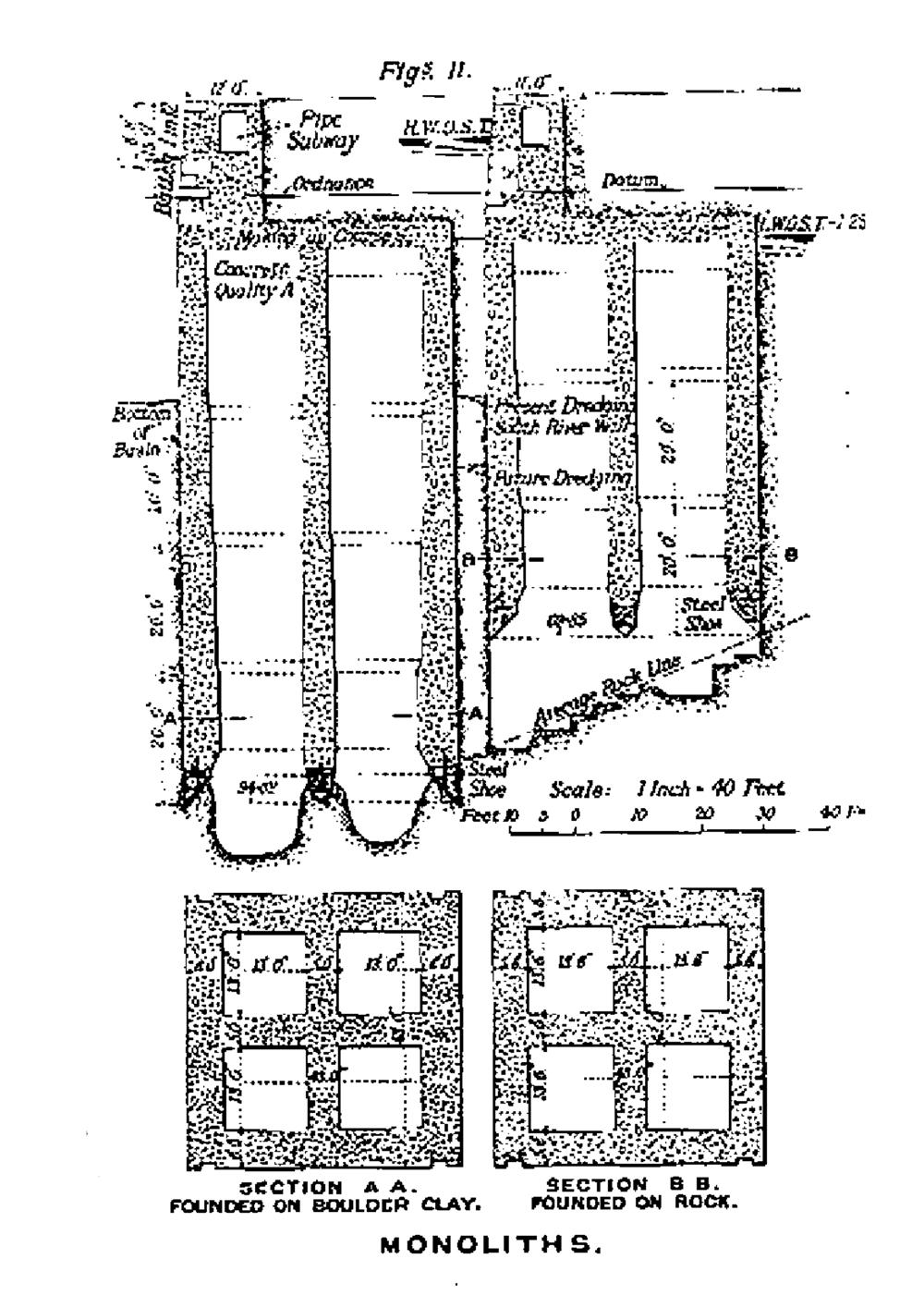

The Admiralty plan for the foundation of the seawalls was to drive 120 hollow concrete monoliths through the seabed sediments to reach a firm base of rock or boulder clay.

The 43ft (13.1m) square and 90ft (27.4m) high concrete monoliths were tipped with steel shoes so that they could be driven through the sediment by loading them with kentledge * (permanent ballast) and excavating sediment from the interior by lowering a grab bucket on a cable through the internal chambers to reach the seabed. (* The term kentledge is probably derived from Old French “quintelage” meaning ballast.)

The contractors developed a method of speeding the sinking process by lowering small charges of “blastine” in tin canisters to about the level of the steel shoe. When these charges were exploded, the concussion of the explosion shook the monolith and the material in which it was embedded, allowing it to sink into the sediment more quickly. This was called “bomb-firing”. The use of bomb-firing was risky, as the blast could cause damage to the monoliths

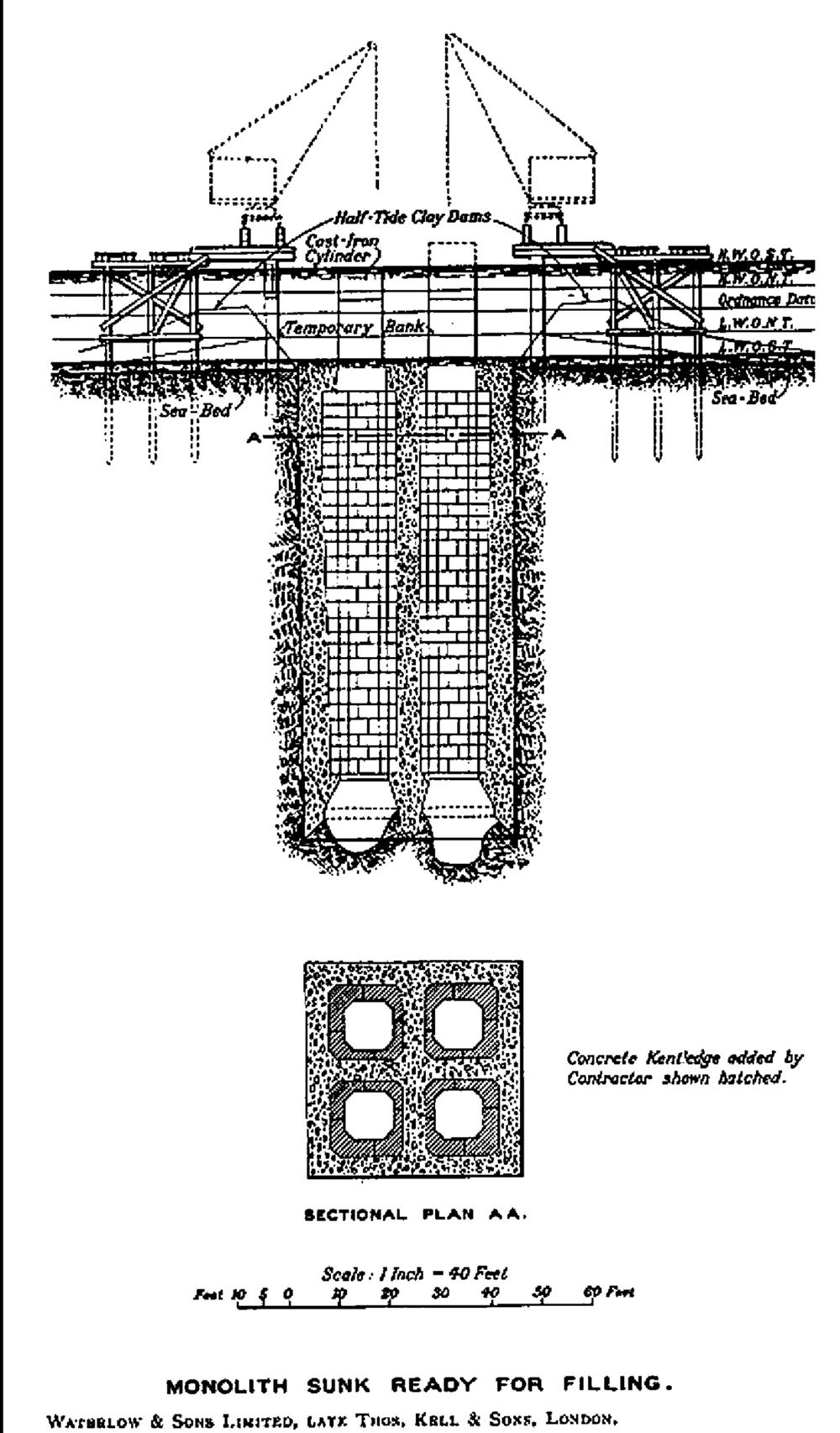

A monolith in place. The cross section shows the concrete kentledge.

Cranes with bucket grabs excavated the sediment from the base of the four wells inside each monolith, allowing them to be driven through the sediment to a firm base.

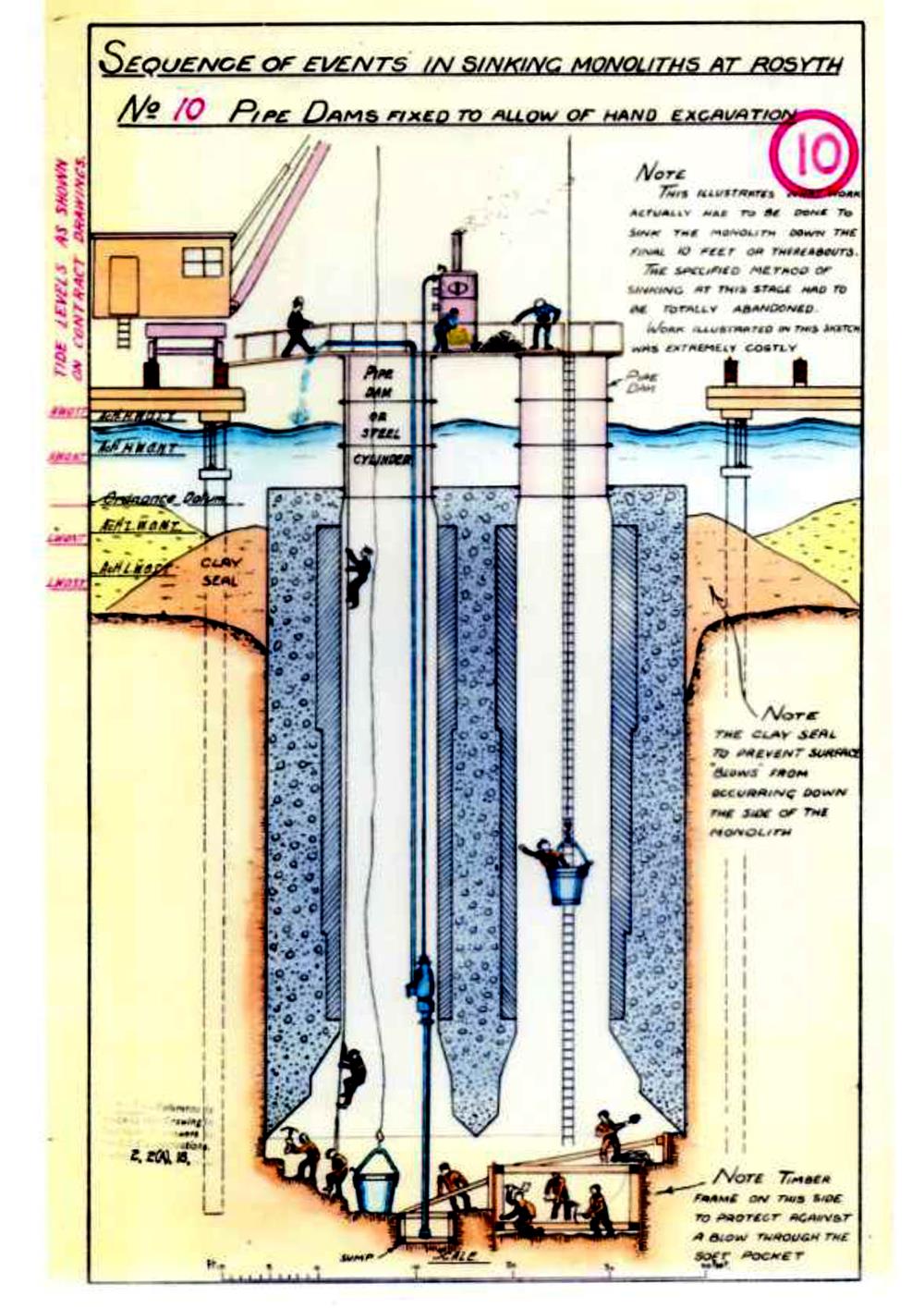

Some of the monolith wells had to be pumped dry, and excavated by hand. This was also a risky undertaking. Sand mud and water could suddenly blow into the well with little or no warning. Happily there were no fatalities, but there were many narrow escapes.

One of the drawings from Easton Gibb’s claim for additional costs involved in the sinking of Monoliths. Although the dockyard work was completed by 1916, final settlement was not agreed until 1922.

One of the drawings from Easton Gibb’s claim for additional costs involved in the sinking of Monoliths. Although the dockyard work was completed by 1916, final settlement was not agreed until 1922.

Once the monoliths were in place, they were filled with concrete, and the reinforced concrete sea walls were built on top.

The gaps between the monoliths which formed the foundations for the walls of the inner basin were shuttered with steel piles, excavated and filled with concrete. The steel piles were then removed.

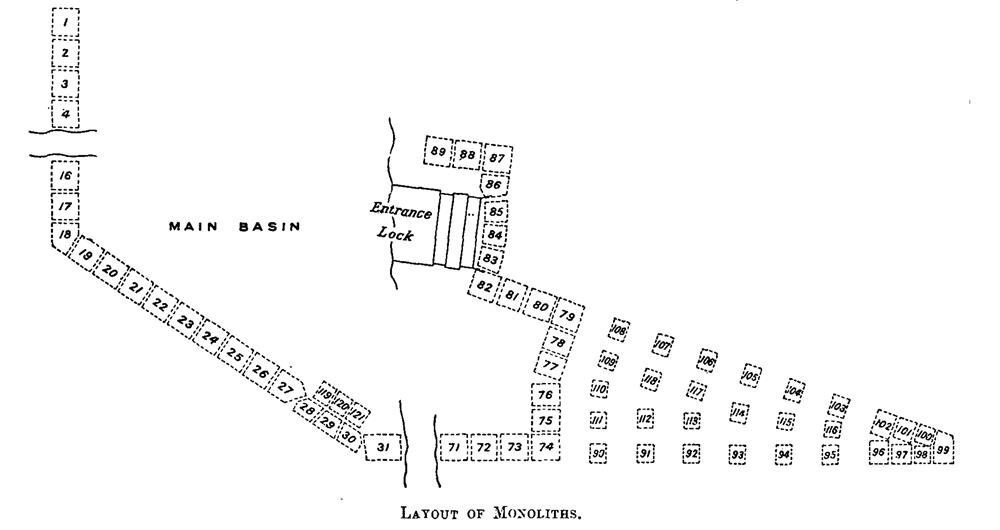

Arrangement of the monoliths round the inner basin and the entrance pier.

Arrangement of the monoliths round the inner basin and the entrance pier.

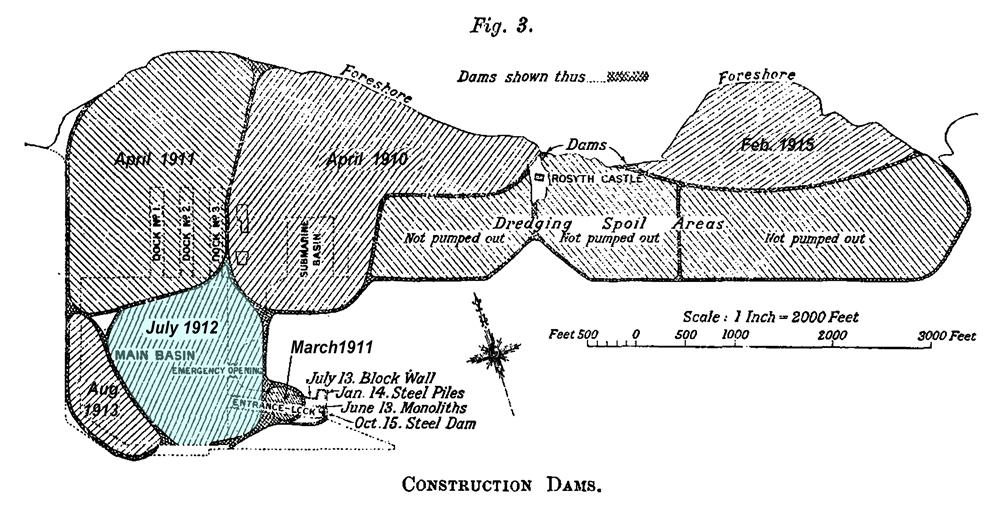

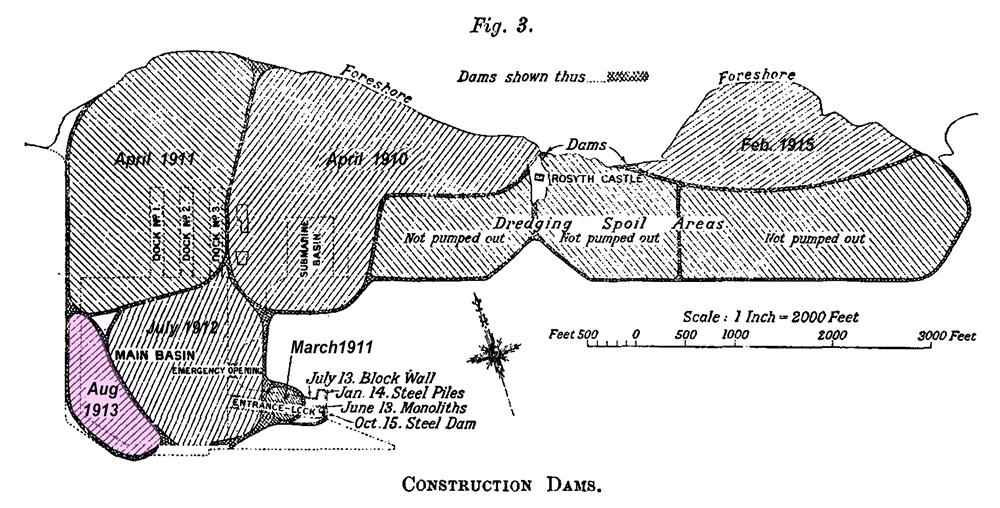

The contract specified that it was not allowed to surround the whole site with a dam. It was intended that the seawalls would be built first, and then the basin and dry docks would be excavated.

However this proved to be difficult in practice. Monoliths founded in boulder clay were difficult to sink; they kept on sticking, and although a heavy weight of kentledge was added using internal concrete blocks, sinking had been by no means a quick or an easy operation. Alexander Gibb believed that it would have been more satisfactory and cheaper to build the outer dockyard wall inside an embankment or coffer-dam, excavating it from sea-bed level in trenches.

Some of the monoliths which were sunk through sand were very deep, and trouble had ensued from sand “blowing” into the wells and caused the staging to sink. As a result the monoliths had tended to get out of place, and progress had been very slow.

Eventually temporary clay dams were created to speed up the whole process.

Temporary clay dams to speed up the rate of monolith sinking in July 1912 . . .

Temporary clay dams to speed up the rate of monolith sinking in July 1912 . . .

. . . and August 1913

. . . and August 1913

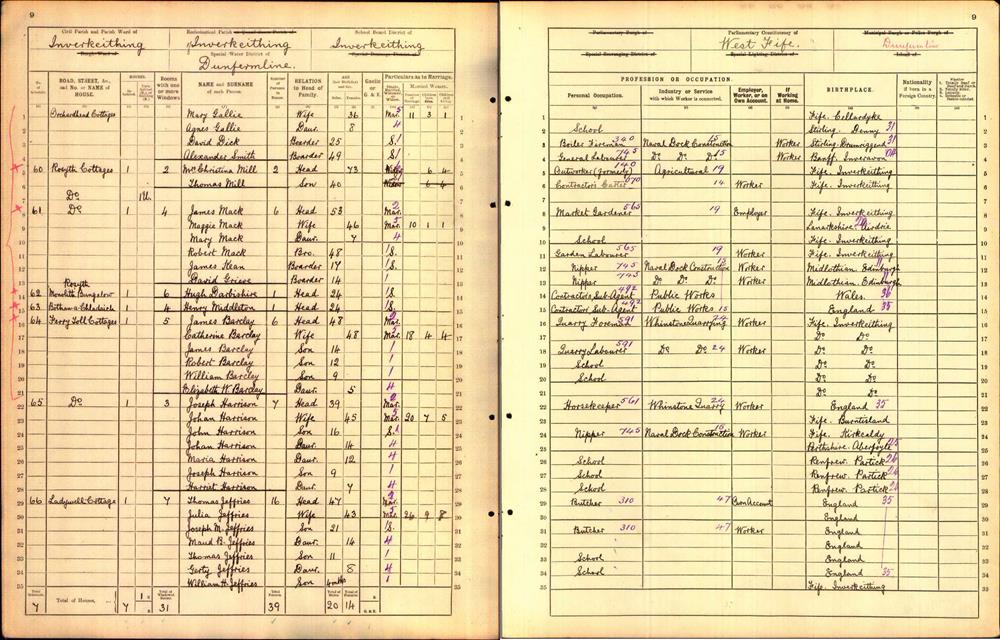

“Monolith” Bungalow

One of the houses on Ferrytoll Road was named “Monolith” Bungalow. The occupant was Hugh Darbishire from Wales, a contractor’s sub-agent presumably working on the Dockyard.

One of the houses on Ferrytoll Road was named “Monolith” Bungalow. The occupant was Hugh Darbishire from Wales, a contractor’s sub-agent presumably working on the Dockyard.

| < 8 – 1910–1911 The North Wall of the Inner Basin and Graving (Dry) Docks | Δ Index | 10 – 1914 Construction progress at the outbreak of war > |