RNAS in WWI

| < Military Aviation in War | Δ Index | RNAS in the Dardanelles > |

The RNAS pilots and aircraft were sent to Belgium and France to provide air support for regiments of marines, who conducted armoured car raids which severely disrupted German reconnaissance activities. Charles Samson’s squadron was heavily involved in this activity and also bombed the Zeppelin sheds at Düsseldorf and Cologne. By the end of 1914, when mobile warfare on the Western Front ended and trench warfare took its place, his squadron had been awarded four Distinguished Service Orders, among them his own, and he was given a special promotion and the rank of commander. He spent the next few months bombing gun positions, submarine depots, and seaplane sheds on the Belgian coast.

On November 21st, 1914, three RNAS aircraft flew from France and attacked the Zeppelin airship sheds and factory at Friedrichshafen on Lake Constance.

Seaplane tenders

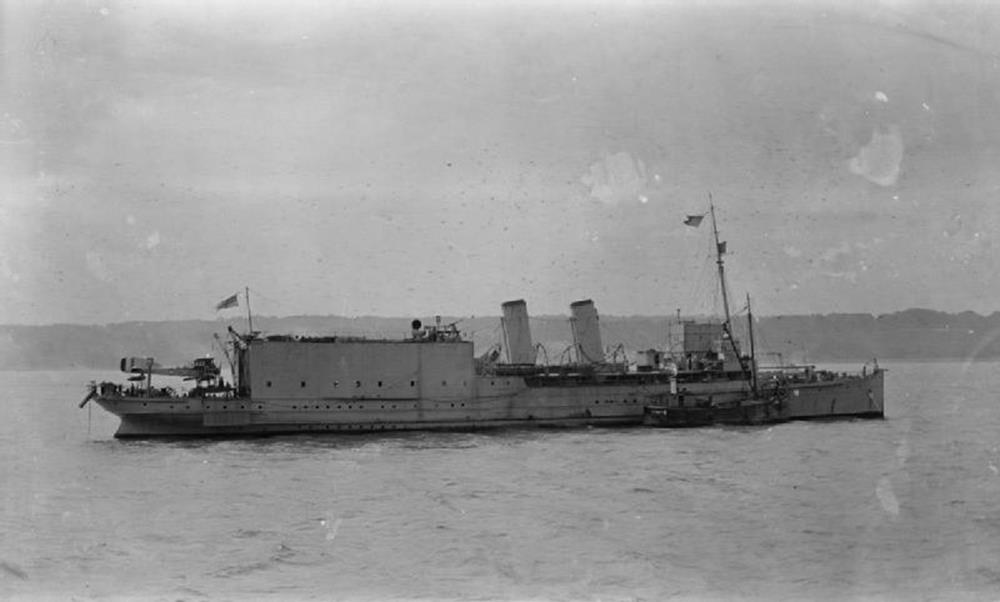

Samson’s success in flying off a moving ship in 1912, prompted the Royal Navy to develop aircraft carriers, of which the first was HMS Ark Royal, launched on 5th September 1914. Originally laid down as a merchant ship, she was converted on the building stocks to be a hybrid airplane/seaplane carrier with a launch platform.

HMS Ark Royal

HMS Ark Royal

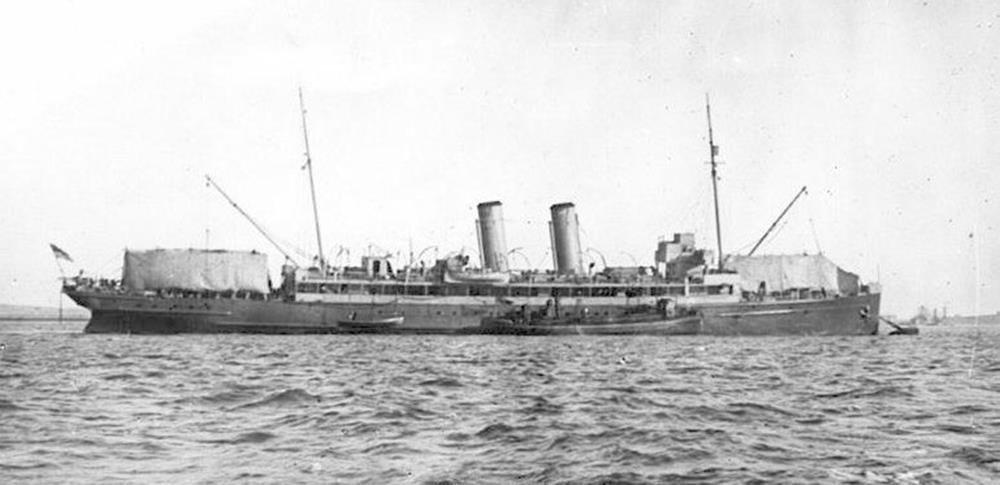

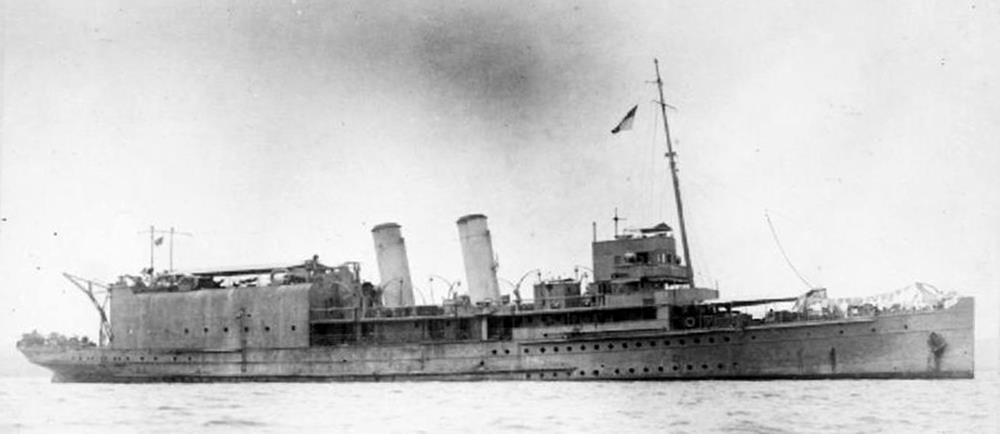

Another flyer from Carlingnose – Francis Hewlett – was involved in The Cuxhaven Raid on Christmas Day, 1914. Three cross-channel steamers converted into seaplane carriers, HMS Engadine, Riviera and Empress carried a total of twelve seaplanes from Harwich to the Heligoland Bight.

HMS Engadine

HMS Engadine

HMS Riviera

HMS Empress

HMS Empress

In freezing conditions the planes were lowered onto the water.

A Short S64 “folder”/p>

A Short S64 “folder”/p>

Two were unable to start, but seven took off, all carrying three 20 lb (9.1kg) bombs).

Fog, low cloud and anti-aircraft fire prevented the raid from being a complete success, although several sites were attacked including the Zeppelin sheds, aircraft hangers and several warships. According to a telegram dated 7 January 1915, held in the Churchill Archives Centre, an intercepted message from Hartvig, Kjobenhaven to the Daily Mail, reported that the raid had forced the German Admiralty to remove the greater part of the High Seas Fleet from Cuxhaven to various places on the Kiel Canal.

The crews of all seven aircraft survived the raid, having been airborne for over three hours.[6] Three, regained their tenders and were recovered; three others landed off the East Friesian island of Norderney and their crews were taken on board the submarine E11. The seventh aircraft, piloted by Flt. Lt. Francis E.T. Hewlett, ditched in the sea. Hewlett was picked up by a Dutch trawler and returned to the port of Ijmuiden in the Netherlands, from where he made his way back to Britain.

[Hewlett gained his pilot’s certificate in November 1911 having been taught to fly by his mother, Hilda Beatrice Hewlett (1864 – 1943) who was the first English aviatrix to earn a pilot’s license. A successful early aviation entrepreneur, she created and ran the first flying school in England, and also created and managed a successful aircraft manufacturing business which produced more than 800 aeroplanes and employed up to 700 people.

Hewlett earned a Distinguished Service Order in 1915 and rose to the rank of Group Captain RAF, and Air Commodore RNZAF.]

After the raid German seaplanes and airships set out to discover the position of the attacking force, and attacked it with bombs. No damage was done to the ship, seaplanes or airship. Further attacks on the retiring force were attempted by German submarines but were unsuccessful and the British force returned to home waters without loss or damage.

The raid demonstrated the feasibility of attack by ship-borne aircraft and showed the strategic importance of this new weapon.

| < Military Aviation in War | Δ Index | RNAS in the Dardanelles > |