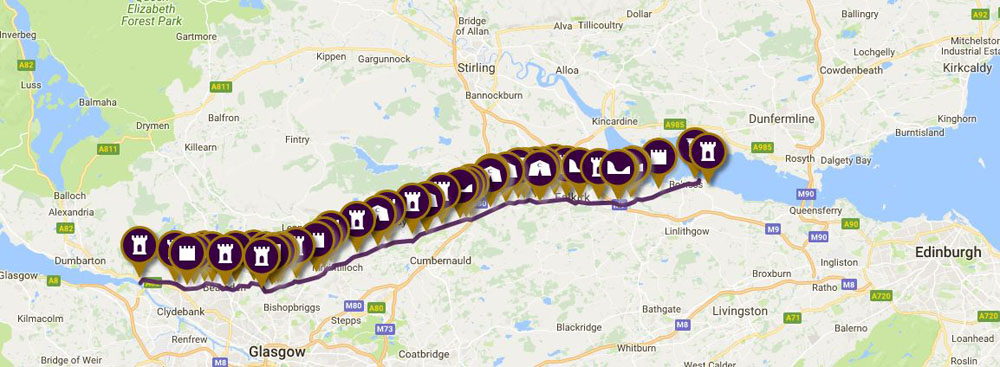

Romans, Angles, Vikings, Normans: successive waves of invaders forced the original clans, tribes and peoples of the British Isles to consolidate, ultimately forming the separate kingdoms of Scotland and England. By the 12th century, the two kingdoms, ruled by separate dynasties, had more or less established their present day borders. Relations between them were marked by intermittent wars and continuous tensions on the border lands, but the River Forth was always a barrier to further invasion. Only the Romans penetrated north of the Forth, and then only briefly. The Antonine Wall, built to bridge the 37 miles between the Forth and the Clyde, was abandoned in 161 A.D. after only twenty years.

Antonine Wall running from Old Kilpatrick on the Clyde to Bo’ness on the Forth

Antonine Wall in Polmont Woods

By the reign of Elizabeth I (1558-1603), some stability was brought to relations between the two kingdoms.

Queen Elizabeth I

The Queen died, unmarried and childless, so bringing her cousin, James VI of Scotland (1557-1625), a Stuart, to the thrones of England and Ireland. This was the Union of the Crowns (1603). James VI and I wanted to be ruler of a new kingdom called ‘Great Britain’.

King James I of England and VI of Scotland I

In reality, his legacy to his son, Charles I (1625-49), was three kingdoms, three parliaments and three state churches. These deep flaws in the Union dominated the 17th century and led directly to civil war, now often known as the ‘War of the Three Kingdoms’.

In 1625, James died and his son Charles I took the throne.

Matters did not improve.

King Charles I

In 1637 a riot broke out in St Giles’, Edinburgh’s main church in protest against a new prayer book which Charles I had tried to force on his northern kingdom.

By 1638, the Scots were in full-scale revolt against the king, with more than half of the population having subscribed a solemn oath – the so-called National Covenant – binding them together as a nation under God. The Scottish Revolution had begun.

In 1639 Charles I staged an abortive invasion of Scotland. Its only success was the brief capture of Inchkeith in the River Forth. In 1640 an army of Scottish Covenanters retaliated by invading the north of England, taking the city of Newcastle, and forcing the King into wholesale concessions. By 1642 the Scottish revolt had become a civil war which engulfed all three of Charles’s kingdoms – England, Ireland and Scotland. The Wars of the Three Kingdoms had begun. It would engulf the Stuart kingdoms and lead to the abolition of the monarchy.

The Scottish Covenanters joined forces with the English parliament in 1643, both subscribing a Solemn League and Covenant, and helped inflict a series of major defeats on the royalist armies, beginning with Marston Moor in July 1644. Charles I surrendered to the Scots in 1646 and sued for peace. Yet victory – and the problem of what to do with the captive King – pushed the allies further and further apart. In February 1647 the Scots went home leaving the King to his fate. Disagreements broke out in both England and Scotland within the once united front of Covenanters and between moderate and radical factions of the English parliament. What the divisions revealed was the different attitudes of the former allies to Charles and to the monarchy itself. The Scots staged a rescue mission and were heavily defeated at Preston in 1648.

But worse was to come. In January 1649, the radicals in the English Parliament led by Oliver Cromwell staged their ultimate coup by putting the King on trial and executing him.

The execution of King Charles I January 1649

Within a few days the Scots proclaimed his son Charles to be their monarch. The English responded by abolishing the monarchy and declaring the nation a Commonwealth under Cromwell.

Oliver Cromwell

This was martial law. Cromwell ruled by the power of his army dissenters kept their heads down – or lost them! The English Parliament wanted an end to monarchy. Scotland wanted a covenanted king. By June 1650, Charles, eventually agreed to accept the Covenants, and sailed from Europe to Speyside in Scotland. Scotland had bound itself once again to the Stuart monarchy. England, in contrast, was now a revolutionary republic under Oliver Cromwell.

In retaliation for Charles’s landing, Cromwell’s army invaded Scotland in July 1650. It marched north from Newcastle, supported by a naval convoy through the captured port of Dunbar. From here it marched on the heavily-fortified city of Edinburgh and Leith. After some skirmishes with the Scot’s army, it fell back on Dunbar to re-supply. The Scots troops, thinking they were seeing a retreat, engaged in battle. This turned out be a disastrous mistake. Cromwell inflicted a severe defeat on the Army of the Covenant at Dunbar on 3 September 1650. The Scots lost over 4,000 men with 10,000 more captured.

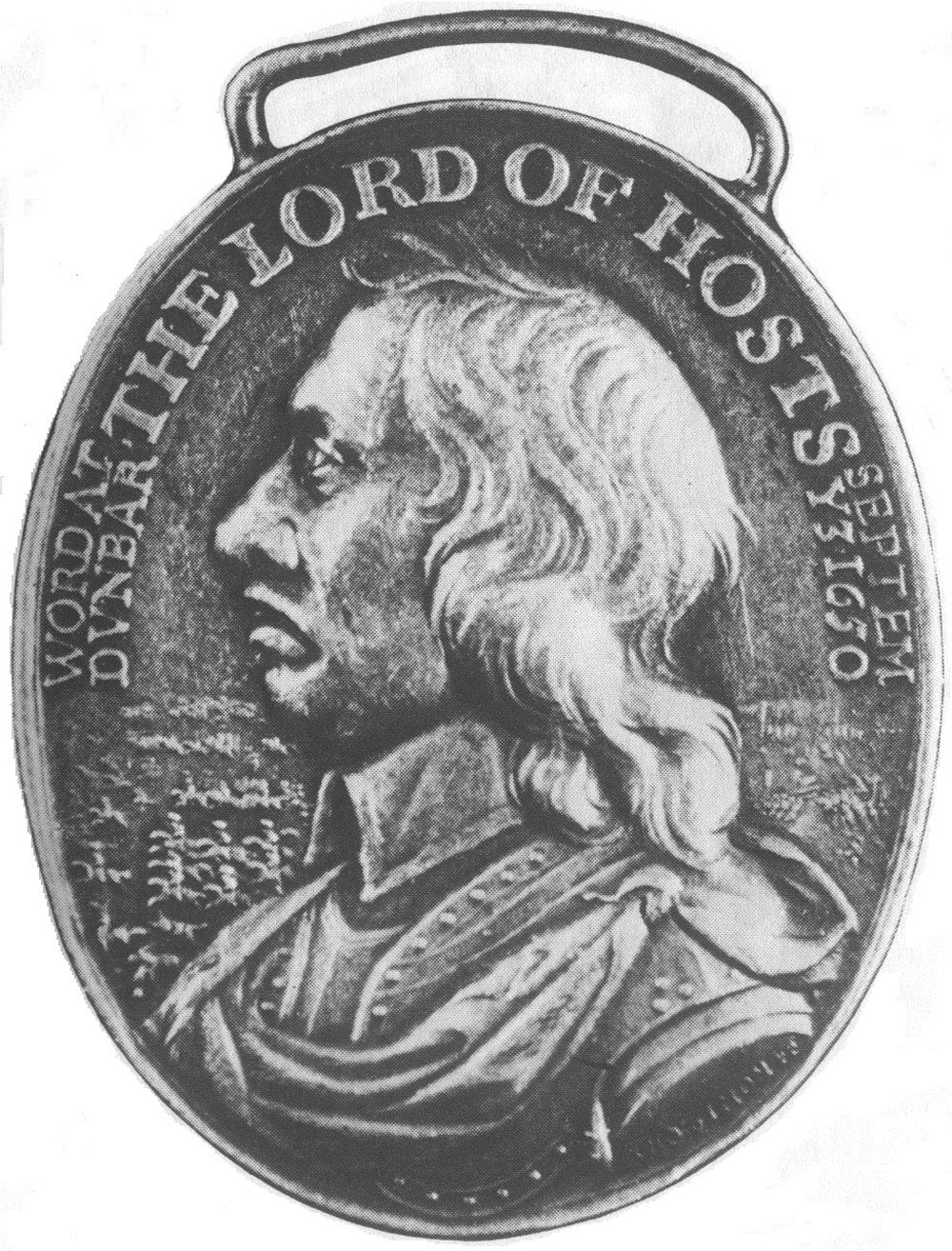

A mere 4,000 mostly cavalry, escaped. All of Cromwell’s troops were awarded the Battle of Dunbar medal, the first to be granted to all ranks of an army.

Battle of Dunbar Medal

The Scottish government and the remains of their army, headed by the veteran General Leslie, withdrew from Edinburgh and headed north of the Forth to Stirling where they were defended by the castle and the river. Charles joined them there to help rally support and rebuild the shattered forces.

Cromwell consolidated his hold on the region around Edinburgh. He laid siege to the castles at Tantallon in East Lothian, and Hume in the Borders. By December 1650 Cromwell had control of Scotland south of the Forth. Edinburgh and Leith were occupied and Edinburgh Castle was eventually surrendered.

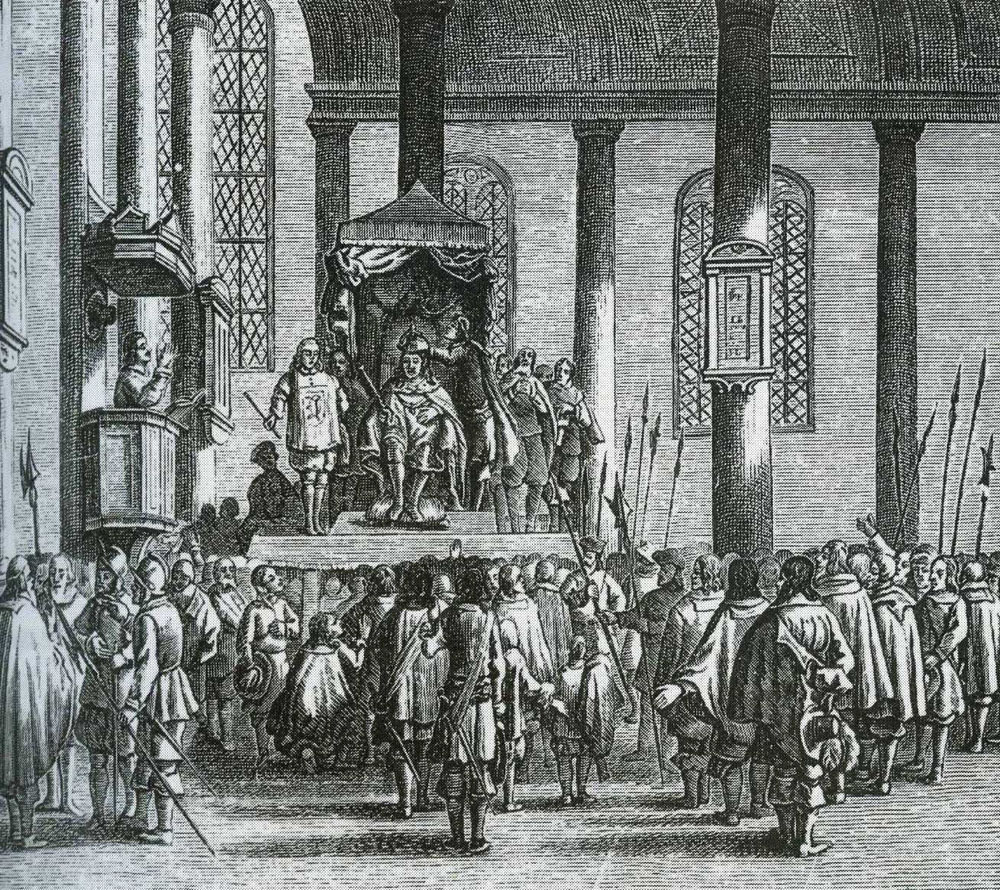

Charles II, still distrusted by the more radical Covenanters, was crowned King of Scots at Scone on 1 January 1651.

Charles II Scottish Coronation at Scone 1 January 1651.

Charles II now wanted to restore the monarchy to England, so he needed to break out of Stirling and head south. Efforts were made to raise a new Covenanting Army of the Kingdom by forced levy and to recruit new colonels to lead it. The results were patchy. The new army was rent by internal divisions – between Lowland recruits and Highland clans, between radical and moderate Covenanters and between shire committees and the more fundamentalist sections of the Kirk. Some of these divisions would come to the surface at the Battle of Inverkeithing. The Army of the Kingdom, although it recruited from every shire in Scotland, was badly stretched. Efforts to assemble a major force at Stirling led to the withdrawal of a number of regiments from Fife.

Cromwell needed to force the Scottish forces out of their stronghold at Stirling to engage them on open ground and gain a decisive victory. Anything less would risk uprisings back in England. He marched his army back and forth across Lowland Scotland, probing for ways to ford the marshy ground to the west of Stirling. Glasgow fell without a fight, and Cromwell established garrisons in the south-west to quell the activities of moss-troopers (border raiders who had harassed Cromwell’s army on its way north.)

The heavily-defended bridge at Stirling posed a formidable barrier to Cromwell’s planned progress north of the Forth. Further east, the river offered the possibility of an alternative way into Charles’s territory, and the chance to cut off his supply chain from Perth and Fife. The Scots were well aware of this and positioned ten regiments of horse along the Fife coast to guard against seaborne attacks. In the early months of 1651 a stalemate followed. Cromwell fell seriously ill and the English army of occupation, low on rations and often without pay in the hard Scottish winter, resorted to widespread plundering and looting.

Cromwell tried twice to probe ways into Fife, once at Burntisland – Fife’s well-defended main port – and later at Rosyth Castle. Each time his forces were repelled.

As the weather gradually improved, Cromwell decided to embark on a daring carrot and stick strategy to winkle out the Scots from Stirling. He withdrew his forces from the south-west leaving a way open from Stirling simultaneously ordering Admiral Deane to prepare a fleet of troop-carrying sailing boats, suitable for a seaborne invasion of Fife. In March, Deane sailed into Leith with his ships, carrying much-needed food and supplies, and a fleet of 27 ‘double shallops’ or sloops, as we would call them, flat-bottomed sailing vessels that could carry men, horses, or artillery pieces.

A shallop

Deane’s navy was key to maintaining Cromwell’s forces in Scotland. As Cromwell’s troops advanced, the navy provided a supply train, first to Newcastle, then Dunbar and eventually to Leith. On average a troop of cavalry – seventy officers and men – would consume about 1.5 tons of bread and 0.75 tons of cheese a month. Their horses would require over 13.5 tons of hay, 4 tons of oats, and 0.1 ton of peas each month. Cromwell’s army was about 16,000 strong, so Deane’s navy was kept busy carrying supplies.

In the early summer the English army trailed their coats in front of Leslie’s forces attempting to draw the Scottish forces out of their strong position and into battle. When this failed, Cromwell’s army fell back on Linlithgow and he sent for reinforcements from England. Colonel Harrison set out from Carlisle taking the east coast route, leaving the route south open to Charles and Leslie. Leslie’s army had been dispersed across a wide area from Stirling in the west to Dundee in the east and Perth in the north living off the land. Seeing the possibility of a breakout to the south Leslie ordered all his regiments to muster at Stirling. Once there, they had supplies for only a few days. Leslie had to take action either break out or disperse again.

Cromwell’s forces were called the New Model Army. They were a full-time standing army of professional, trained, drilled, disciplined, specialized troops. The Scots Army was formed on an ad-hoc basis, some were veterans, but many were raw recruits or pressed men. Many officers and men on both sides had fought in the Thirty Years War (1618 to 1648) which raged across Europe from Spain to Sweden. This experience shaped their arms and tactics.

Infantry regiments consisted of Pikemen and Musketeers.

Pikemen

Pikemen formed a defensive core with sixteen-foot pikes pointing forwards, to guard against cavalry opposing forces of infantry would engage like rugby scrums – each side pushing forward with their pikes to try to break the opposing formation.

A Musketeer

Musketeers formed up on each side of the Pikemen firing in rows or en-masse in volleys. Each musketeer carried a bandolier of cartridges containing shot and powder for their muzzle-loading muskets, along with a small flask of fine powder to prime the musket. A slow-burning match was used to fire the weapon. These heavy matchlock guns were supported on a stand. While they were not very reliable or accurate, they were deadly at close quarters.

Infantry regiments were often flanked by Cavalry regiments organized in troops of about 100 men, each armed with a sword and two single-shot pistols. They would engage the enemy firing their pistols from as close as they could approach, hoping to break the masses of pikemen. In response the pikemen would close ranks, and shield their musketeer comrades.

A Cavalry-man

These tight formations made compact targets for artillery.

A demi-culverin

Both sides had a range of cannon, from siege guns used to destroy castle walls, to smaller battle-field guns like this demi-culverin. With an effective range of 500 metres its 4kg cannonballs could wreak havoc in a close-packed formation of pikemen.

Cavalry could then race in and engage before the unwieldy pikes could be redeployed.

A Scots Lancer

Along with cavalry armed with swords and pistols, the Scots used lancers who carried a long spear.

A Scots Archer

The Scots in particular made use of archers. Arrows were as deadly as musket-balls, and archers could maintain a higher rate of fire with greater accuracy. But it took time to train an archer, who had to be physically strong, while it only took an hour to train a conscripted musketeer.

A Dragoon

Both sides also used dragoons, mounted musketeers who could be deployed quickly on the battle-field to reinforce defences or bolster an attack. Dragoons fought on foot. Their horses were neither fit enough nor battle-trained to serve as cavalry horses.

The Sealed Knot society enacts battles from the era, and kindly provided the following images.

On June 28th 1651, Leslie’s men cautiously left Stirling, and set up camp on a hill at Torwood, protected in front by marshy ground and the River Carron. A few inconclusive skirmishes ensued, Cromwell bombarded and recaptured Callendar House at Falkirk but Leslie stayed at Torwood.

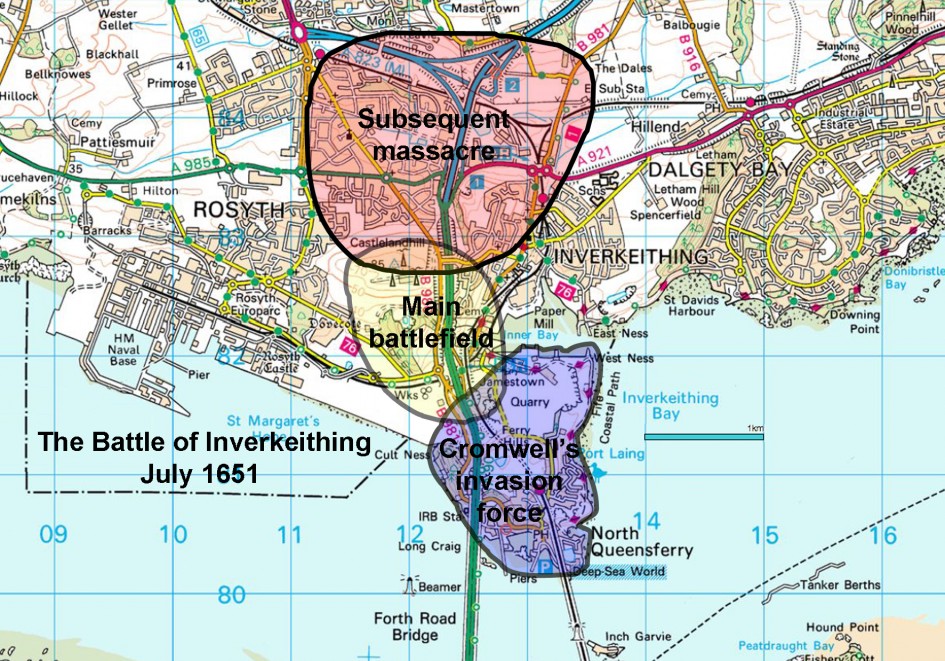

On Wednesday 16th July, Cromwell learned that Col. Harrison was close to Leith with 2,500 infantry and 1,500 cavalry and dragoons. He ordered Colonel Overton to march out of Leith with 1,500 infantry and head west towards Linlithgow. By that evening they were halfway there but instead of camping for the night, they slipped north and sailed over the Forth to North Queensferry in Deane’s fleet of boats.

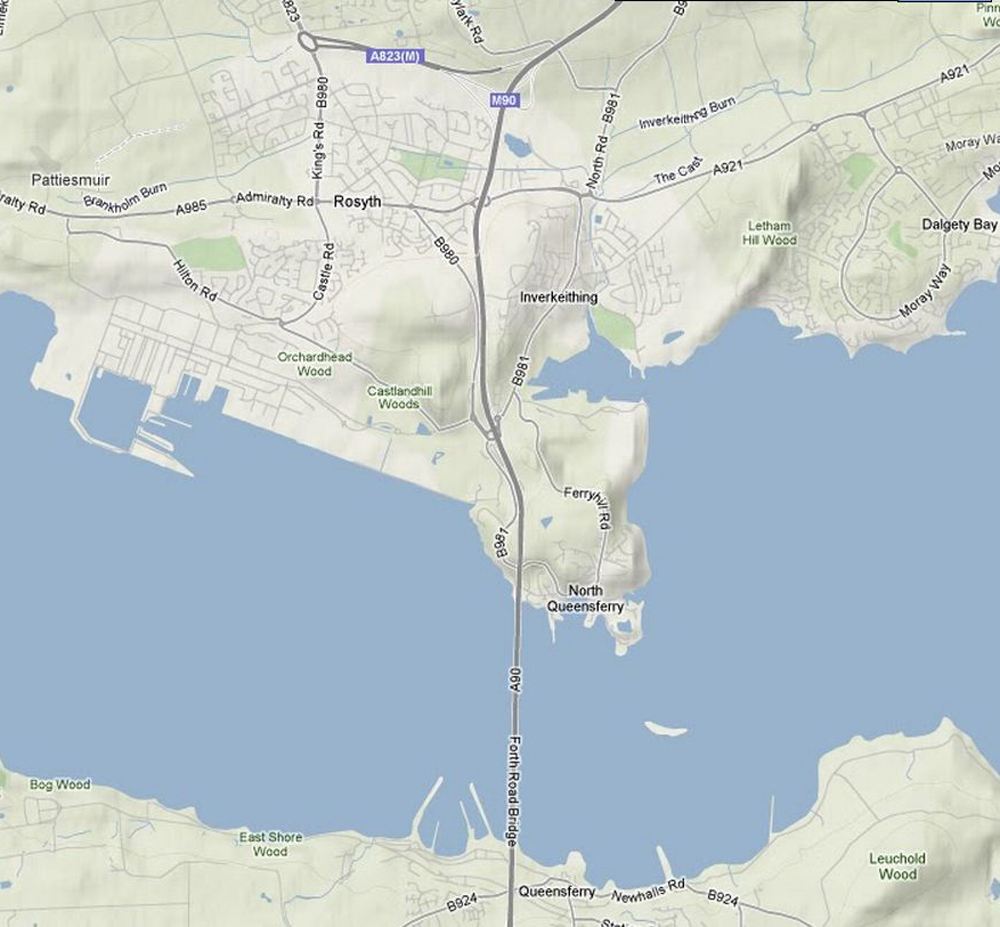

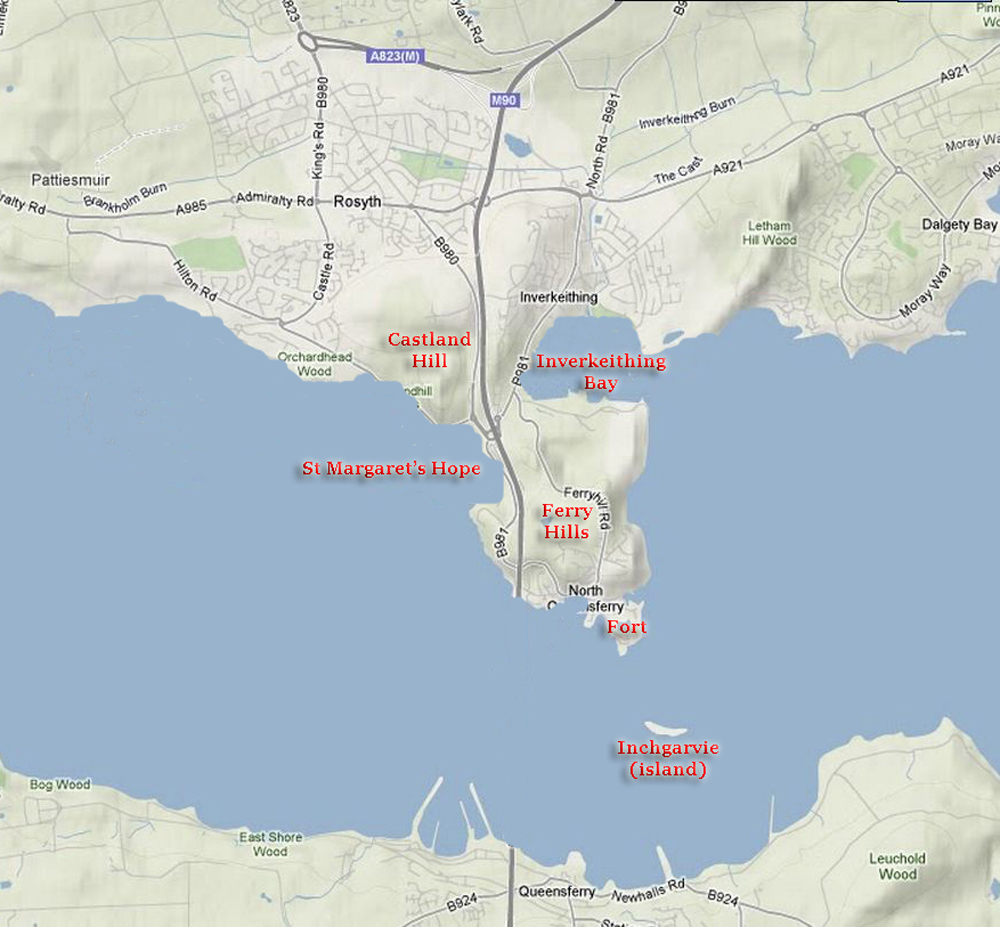

The coastline has changed significantly since the time of the battle, with major land reclamation in the early 20th century between North Queensferry and Rosyth. These maps show the coastline as it is at present (left) and as it was in Cromwell’s day (right.) The peninsula of North Queensferry was much more isolated, with a much narrower neck between Inverkeithing Bay and St Margaret’s Hope. St Margaret’s Hope provided a large safe haven for shipping. Inverkeithing Bay was larger, and Castland Hill swept down to the shores of the river.

The Forth defences included a heavy battery at Burntisland, a battery of 16 cannon on Inchgarvie island plus the defences of North Queensferry itself – 12 cannon on the Ferry Hills, 5 cannon in the Fort, and an armed guardship in the sheltered waters of St Margaret’s Hope.

While these guns were all capable of sinking a ship, they were not very accurate with an effective range of no more than 500 metres. Deane had been testing these defences for some months. Some of his ships had slipped past Inchgarvie and captured the guardship in the Hope. He found that if he sailed some ships close to the defences, others could slip past in the confusion.

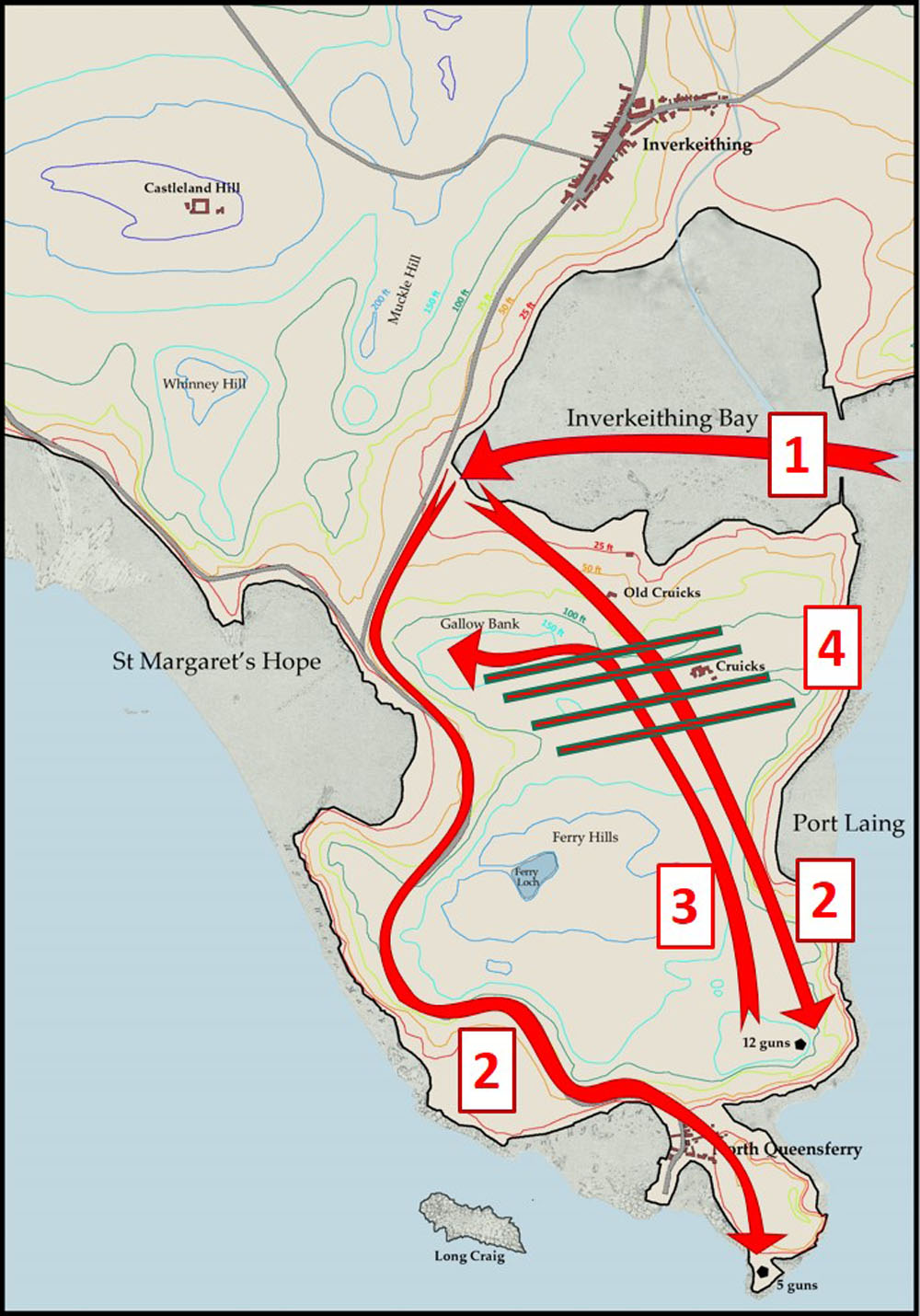

All night on Wednesday 16th July 1651, Overton’s men crossed the river landing at the neck of the peninsula behind the defensive batteries (1.)

Heading back south over the Ferry Hills they overcame the local battalion and captured the guns of the shore batteries (2.)

They had established a tentative beachhead in Fife. On Thursday and Friday they slaved to consolidate their position. They dragged some of the captured guns round to the top of Gallow Bank, where they dominated the approach from the land (3) and dug defensive earthworks and trenches across the north-facing slopes of Ferry Hills (4).

While Overton launched the initial invasion, Cromwell pressed on from Linlithgow towards the Torwood. He may have hoped that news of the successful landing would pull the bulk of the Scots army towards Fife. On learning that the Scots had dispatched only a relatively small force but one sufficiently strong to rebuff the invasion he ordered Col. Lambert to reinforce Overton’s beachhead and take command of the invasion force. On Saturday 19th & early Sunday 20th Lambert ferried nearly 3,000 of his own troops and horses from Blackness (a port on the river near Linlithgow.) Landings took place all round North Queensferry. As each regiment arrived, the troops furiously dug further protective entrenchments. Lambert’s troops stood behind the entrenchments until the landings were complete. By the morning of Sunday 20th July about 5,000 men (3,500 infantry plus 1,500 cavalry and dragoons) had arrived and were dug in on the peninsula.

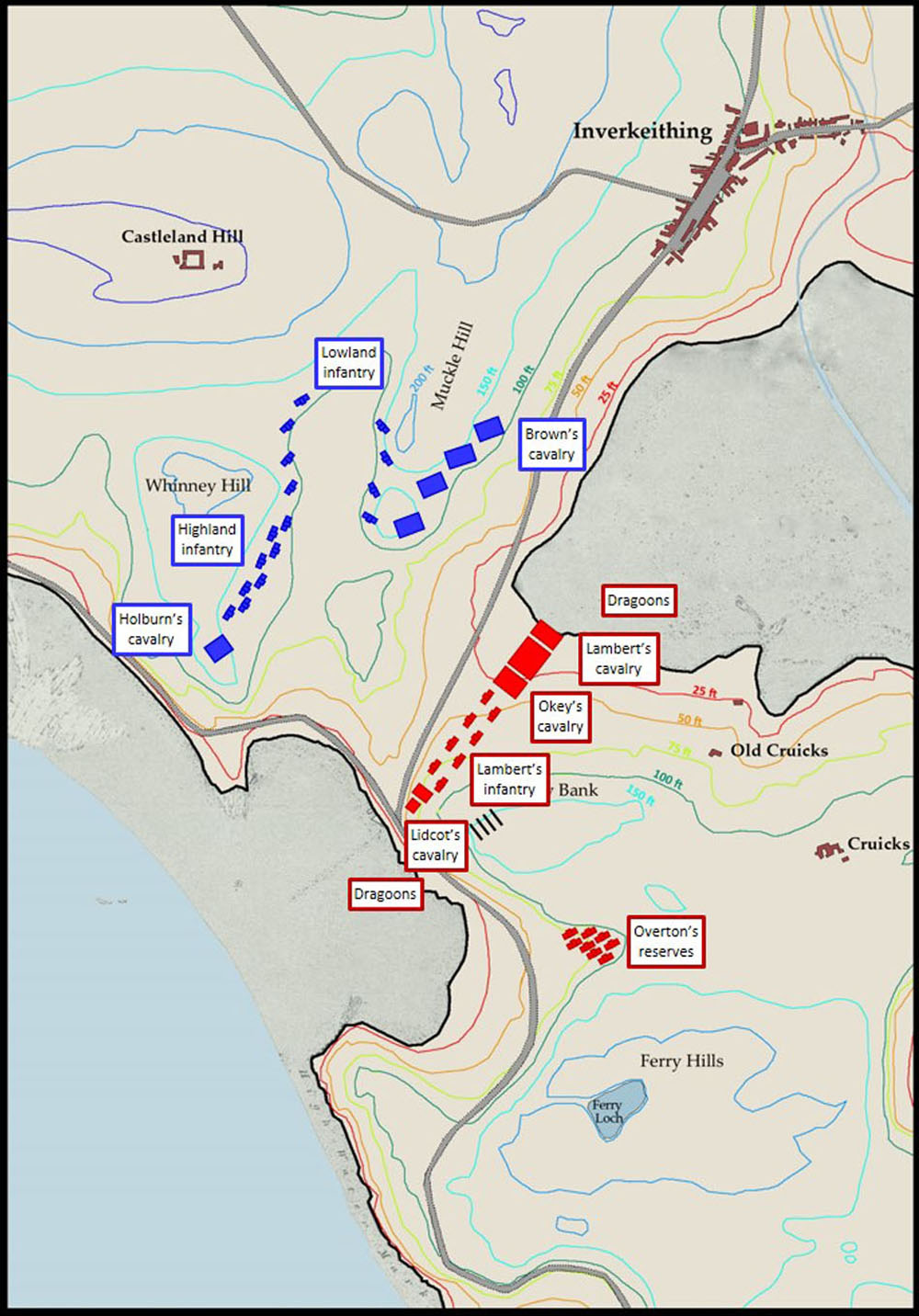

The landing activity had not gone unnoticed. A Scots army of 3,000 infantry led by Lt. Gen. Holburn and 1,400 cavalry commanded by his friend Sir John Brown was dispatched from Stirling to Dunfermline.

Having camped at Dunfermline overnight, they marched towards Inverkeithing on the morning of Sunday 20th of July, arriving as the last of Lambert’s men scrambled ashore.

The Scots forces were an awkward mix. Holburn commanded two Lowland infantry regiments, his own of about 650 men, and the Master of Gray’s about 600. These were complemented by two Highland regiments drawn from the Clans Maclean (800 men) and Buchanan (890). These regiments had only just arrived at Stirling with no time to integrate before being dispatched to Fife. In addition they were not friendly towards Holburn and Brown who were the protégés of rival clans, so the Highlanders operated more or less independently under their clan chiefs.

The Scots gathered some local recruits in Inverkeithing and marched along the main road towards North Queensferry.

In response to the approaching threat, the English had formed up into their standard cavalry – infantry – cavalry formation.

Lambert placed his strongest cavalry force under Col Okey on his right, half his infantry in the centre and a smaller force of cavalry under Col Lidcot on his left wing. They were squeezed into a very narrow front across the isthmus The other half of his infantry, led by Col Overton, was held in reserve, completely hidden in the Welldean valley behind Gallow Bank.

As the Scots force advanced, Lambert sent out a small force of cavalry, perhaps hoping to fool the Scots into a rash attack on an apparently small force. But Holburn was cautious, and wheeled his column right to take advantage of the high ground on the three hills which face Lambert’s position – Whinney Hill, Castland hill and Muckle Hill. Lambert ordered Okey’s cavalry to harass the Scots rear as they turned to take up position.

Holburn positioned his troops in standard formation, mirroring Lambert’s deployment. He placed his own regiment of cavalry on his right wing on the slopes of Castland Hill (looking north today it is crowned with radio masts) flanking the Highland infantry.

Brown took command of several other cavalry regiments over on Muckle Hill (topped with houses today.) The Lowland infantry lined a pass between these hills (the path of the motorway north today) with musketeers to prevent an English breakout from the peninsula.

Okey’s cavalry fell back to the English lines, and the two armies settled in to observe each other’s strengths and weaknesses. Neither side had a decisive weight of numbers, they were each waiting or hoping for further reinforcements. The Scots only had to keep Lambert’s force bottled up, while Lambert had to break out of the peninsula.

Lambert started the campaign with the captured guns on Gallow Bank which began a murderous sweep across the opposing forces, causing many casualties in the Highland regiments. He hoped to reduce the strength of his opponents while waiting for news of further reinforcements from across the river. Time marched on with neither side willing to launch an all-out attack.

By mid-afternoon, on Sunday 20th July both sides were locked in an effective stalemate. Eventually a small boat arrived at North Queensferry with news. Cromwell was waiting for Leslie to head South from Torwood so he would not be sending reinforcements to Lambert. Lambert greeted this news by launching an attack.

He led his right-wing cavalry in a charge up the slopes of Muckle Hill into the face of the main body of Scottish cavalry commanded by Sir John Brown. They in turn counter attacked but gradually lost the initiative and through inexperience failed to regroup after the initial engagement and fled from the field. This exposed the left flank of the Lowland infantry who fought back with musket fire. Holburn’s own cavalry on the Scottish right-wing launched an attack against Lambert’s weaker left-wing cavalry and were initially successful.

Holburn’s cavalry managed to regroup after the initial engagement but were in a tight corner menaced by the English dragoons and infantry. At his point, Overton’s reinforcements emerged from hiding. General Holburn realized that he had underestimated the strength of his opponents and ordered a retreat. His cavalry and the Lowland infantry withdrew in some disarray but the Highland infantry refused to go and stood their ground, opposed in front by the full force of Lambert’s infantry, and now outflanked by cavalry on both sides.

The main battle was effectively over after an engagement that had lasted about fifteen minutes.

Worse was yet to come. The Highlanders refused to surrender and were gradually driven north for mile after mile all the way to the walls of Pitreavie Castle. Pursued relentlessly by Lambert’s forces, their numbers were gradually whittled down.

On the way North, the Highlanders rallied for one last stance and a terrible struggle ensued. Despite being surrounded by superior numbers the MacLeans and Buchanans refused to give way, and were cut down almost to a man. Of the 890 men in Maclean’s Foot only thirty-five lived to see their homes again.

Aftermath of the Battle At the end of a battle which lasted at most a few hours, the Scots had lost between 1,400 and 2,000 men, with 1,500 to 1,800 taken prisoner. English losses were light, as most casualties took place in the rout after the main battle.

Locally, Cromwell’s army destroyed much of St James’s Chapel in North Queensferry.

Chapel of St James in the 1890s

Back at Torwood, Leslie faced a quandary. He could not head south with Cromwell’s main force waiting at Linlithgow. If he headed into Fife, Cromwell could cross at Stirling.

He rushed back from Torwood to his stronghold at Stirling leaving his camps standing, abandoning dead and wounded soldiers and quantities of food and ammunition. He headed east into Fife to threaten Lambert’s invasion force.

Cromwell and a scouting party tracked them along the south bank of the Forth following them as far as Bannockburn, observing them through “prospective glasses” (a telescope.) Convinced that most of Leslie’s army was on its way to Fife, Cromwell ordered his army back from Linlithgow to cross into Fife at Queensferry.

Leslie in turn observed and acted. Once Cromwell’s scouting party left Bannockburn, he turned back to Stirling. The way would now be clear to break out and head south to England.

Cromwell chose to ignore Leslie’s change of direction, indeed he may have welcomed it. With Leslie’s army heading south, Cromwell could take his time in crossing to Fife and then head north to take Perth.

The capture of Perth sealed Charles’s fate. His supply lines were severed and he could no longer retreat to his stronghold in Stirling.

On 31st July, Charles headed south with part of Leslie’s army leaving a garrison behind at Stirling.

The psychology was now reversed Charles would be leading an invading Scot’s army into England. Many of the Scottish soldiers had wanted only to defend Scotland from Cromwell’s invasion. They gradually drifted away as the army headed south.

After the conquest of Perth, Cromwell split his army. On 5th August he ordered Lambert and Harrison to take their cavalry and harass the Scots army. Lambert followed the Scots down the south-west route past Carlisle while Harrison took the south-east route past Newcastle.

General Monck assumed command of all of the artillery and a relatively small force of infantry and cavalry. He was tasked with the conquest of the Highlands.

Cromwell then took the bulk of his seasoned infantry south in careful measured stages, conserving their strength and morale.

Charles continued to head south gaining a little support in some districts while being rejected in others. He eventually reached Worcester on August 22nd and was allowed into the city. The Scots army was back in a defensive stronghold but was now surrounded by hostile forces with no supply route.

Meantime Monck used his artillery to batter first Stirling and then Dundee into submission, plundering them in retribution for their defiance. Other towns chose to surrender and be spared.

Charles and his men were psychologically depressed by the bad news of Monck’s advances in Scotland. Physically they were worn down as Cromwell began an artillery bombardment of Worcester.

On three sides, Worcester was defended by city walls, and on the fourth by the River Severn. Leslie’s men had destroyed the bridges over the Severn so they were in a very strongly defended position. But Cromwell found a way to cross. Collecting all the boats he could find along the river he built pontoon bridges over the Severn invaded the city and defeated the Charles’s forces. Cromwell had won his decisive victory, in the last battle of the war, on 3rd September 1651.

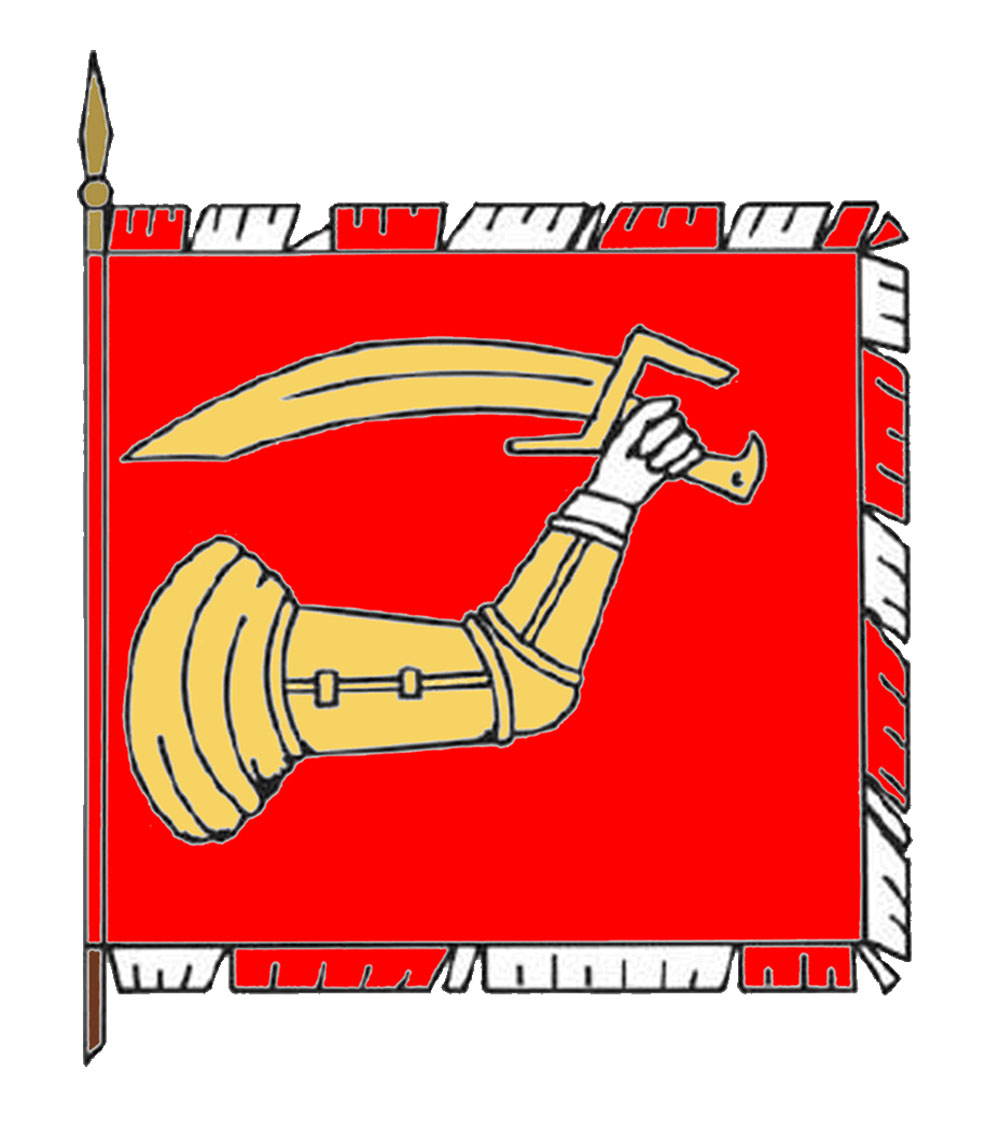

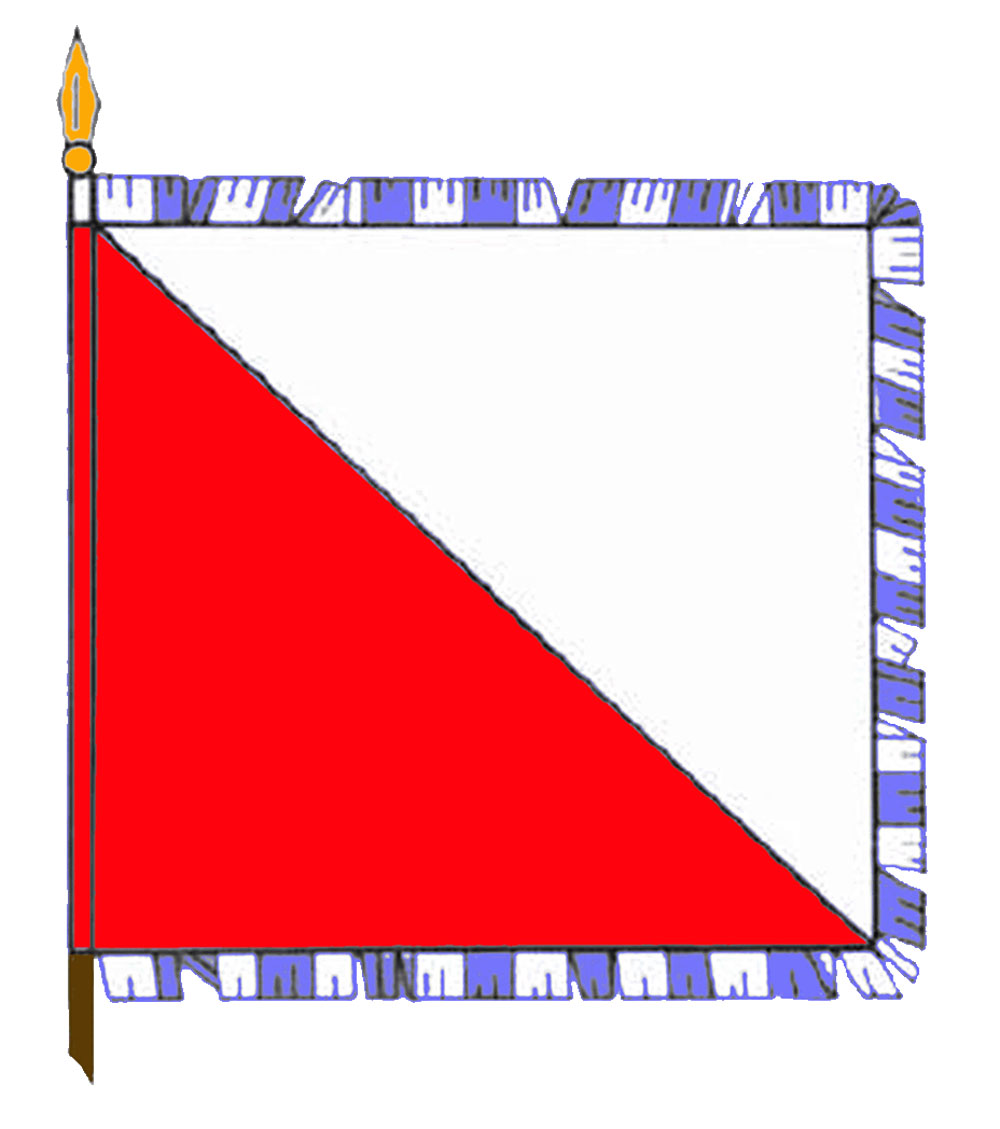

After each of the battles the colours of the defeated regiments were seized as trophies. These were taken to London and displayed at Cromwell’s triumphant procession into the city.

The House of Commons journal records that on Wednesday the 10th of September 1651 the colours were hung in Westminster Hall. They remained there until Thursday May 10th 1660 when they were taken down and presumably put into storage. Their ultimate fate is unknown but they were most probably lost in the fire which destroyed Westminster in 1834.

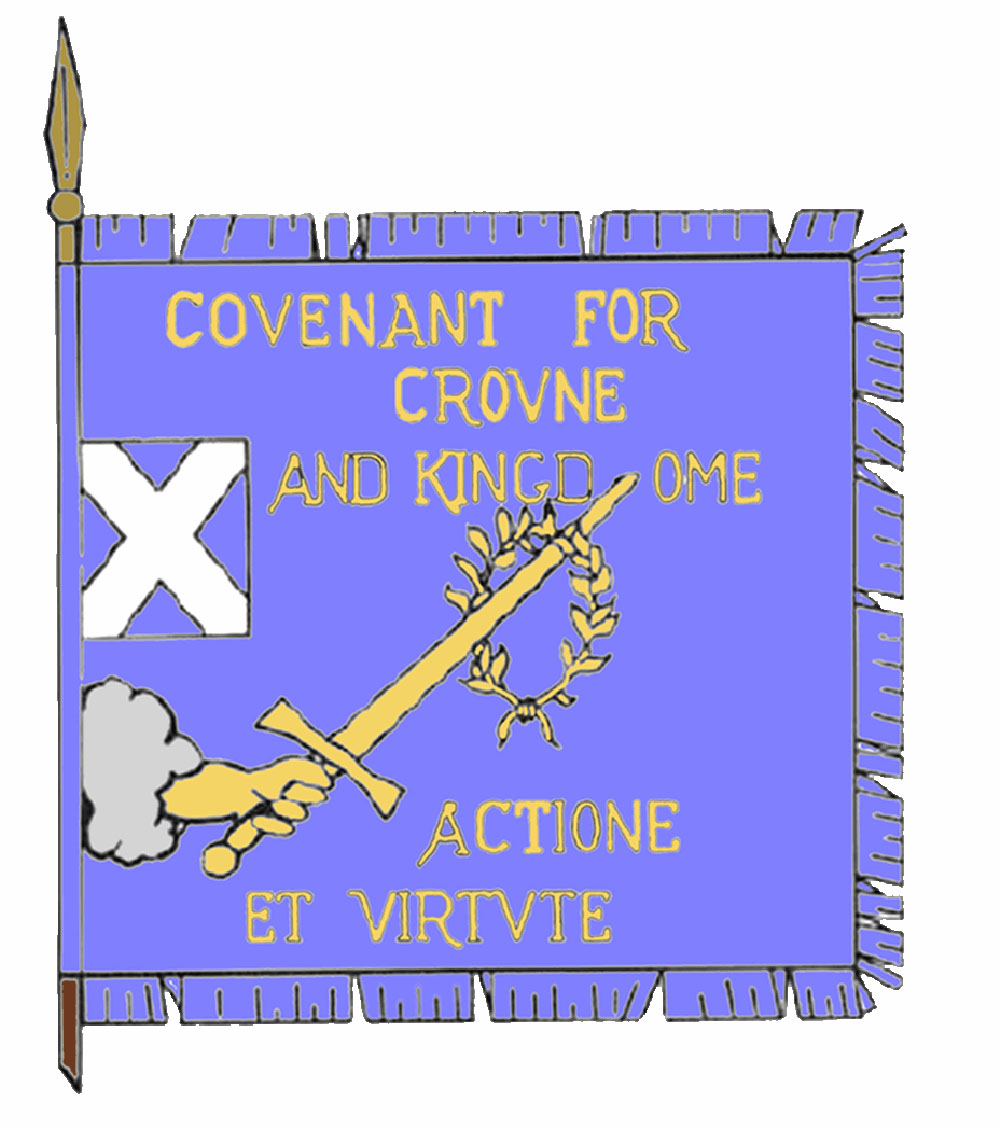

Here are four colours which were captured after Inverkeithing.

At Worcester 3,000 defeated Scots were slain and 10,000 captured. Some 8,000 of these Scottish prisoners were deported to New England, Bermuda and the West Indies to work as indentured labourers. Ironically some of their descendants would eventually become slave owning landlords.

In Scotland itself the aftermath was a bloody one. The town of Dundee was sacked. The country was occupied by 10,000 English troops and a chain of citadels was set up across Scotland. This was the largest scale occupation Scotland had ever experienced.

Scotland and England became one republic under Cromwell. This was a very different kind of Union from the Union of the Crowns established in 1603.

Scotland was represented in Parliament at Westminster for the first time. Free trade extended across the republic. Scotland was in too poor a state to benefit. Free trade ended with the Restoration of Charles II in 1660 and the Scottish Parliament was re-established. But the experience of the 1650s would have one final effect. It helped produce some of the key factors which led to another kind of Union. The Union of Parliaments came about in 1707.

Although the Battle of Inverkeithing was a pivotal moment in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms and indeed in Scotland’s history it is often overlooked in history books.

While there is broad agreement on the story of the build-up to the battle and its outcome there is much less certainty over the detail of the battle itself.

The few original documents which describe the battle are short on detail and often contradictory. The account which we have given here is based on our analysis of the original documents.