Stalemate in Scotland

| < Cromwell invades Scotland | Δ Index | Breaking the Stalemate > |

The Scottish government and the remains of their army, headed by the veteran General Leslie, withdrew from Edinburgh and headed north of the Forth to Stirling where they were defended by the castle and the river.

The heavily-defended bridge at Stirling posed a formidable barrier to Cromwell’s planned progress north of the Forth. Further east, the river offered the possibility of an alternative way into Charles’s territory, and the chance to cut off his supply chain from Perth and Fife. The Scots were well aware of this and positioned ten regiments of horse along the Fife coast to guard against seaborne attacks.

Charles joined them there to help rally support and rebuild the shattered forces.

Cromwell

Before making further progress, Cromwell needed to consolidate his position. There were still pockets of opposition south of the Forth in strong holds such as Edinburgh Castle, where miners attempted to blow the castle walls, Tantallon Castle, and Hume Castle.

The southwest corner from Carlisle to Glasgow was held by the Western Association. Originally an anti-Royalist organization, it was opposed to Cromwell’s invasion. In October, Cromwell headed west, and Glasgow surrendered without a fight – the magistrates and “chief of the town” having fled.

In November, a party of 3,000 horsemen under Colonel Montgomery set out from Stirling to take command of the army of the Western Association. He was eventually trapped by Cromwell and Lambert near Hamilton, and his forces were scattered. This broke the will of the Western Association who more or less disbanded. (Montgomery escaped, and a few months later, he was successful in pushing Cromwell’s forces out of the South West.)

Edinburgh Castle withstood the siege for several months while the Scots gathered strength north of the Forth, supplying Charles’s army at Stirling from Perth, and the rich farmlands of Fife. It eventually surrendered on 24th December, having been subjected to weeks of bombardment.

Charles

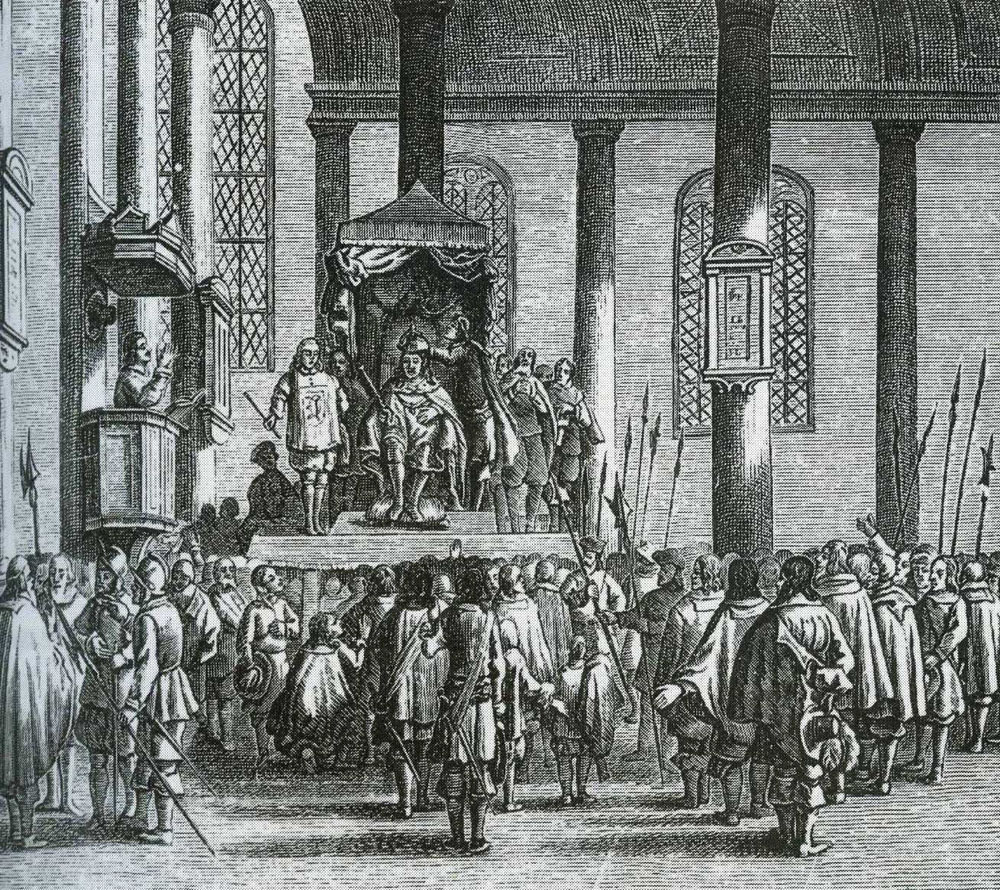

Charles, still distrusted by the more radical Covenanters, was crowned King of Scots at Scone on 1 January 1651.

Charles II Scottish Coronation at Scone 1 January 1651.

Charles II Scottish Coronation at Scone 1 January 1651.

Charles wanted to restore the monarchy to England, so he needed to break out of Stirling and head south. This meant replacing the losses at Dunbar by raising a new Covenanting Army of the Kingdom through forced levy and to recruit new colonels to lead it.

He embarked on a tour of his new kingdom, building up support for Leslie’s army. He was still a figurehead, not a commander.

While touring through Fife, Charles enjoyed a round of golf at Largo, and inspected the batteries at Inchgarvie North Queensferry, and Burntisland, which as the principal port of Fife was very important to his supply chain. North Queensferry contained “a little fort with 5 guns, flanked by batteries on the Ferry Hills” – containing a further 12 guns.

The recruitment results were patchy. The new army was rent by internal divisions – between Lowland recruits and Highland clans, between radical and moderate Covenanters and between shire committees and the more fundamentalist sections of the Kirk. Some of these divisions would come to the surface at the Battle of Inverkeithing. The Army of the Kingdom, although it had recruited from every shire in Scotland, was badly stretched.

Cromwell’s response

Cromwell needed to force the Scottish forces out of their stronghold at Stirling to engage them on open ground and gain a decisive victory. Anything less would risk uprisings back in England. He marched his army back and forth across Lowland Scotland, probing for ways to ford the marshy ground to the west of Stirling. Glasgow fell without a fight, and Cromwell established garrisons in the south-west to quell the activities of moss-troopers (border raiders who had harassed Cromwell’s army on its way north.)

In February 1651, Cromwell’s army set off from Edinburgh on an expedition towards Stirling. They went as far west as Kilsyth, with stops at Falkirk and Linlithgow before heading back through wintry weather to Edinburgh.

While the castles at Hume and Tantallon were potential barriers to the eastern route to England, the Scots battalions at Callendar House near Falkirk, and Blackness Castle on the Forth near Linlithgow, were of more immediate concern to Cromwell, as the whole area to the South of Stirling was still contested by the Scots. Blackness was seen as a convenient landing place for raids on Cromwell’s forces at Linlithgow – and had been used by Augustine and his moss-troopers in December when they made a bold relief run to Edinburgh Castle.

(The moss-troopers were originally border raiders who had harassed Cromwell’s army on its way north. Augustine, who had been a captain in Leslie’s army, organized them into a semi-independent cavalry unit.)

Cromwell took Callendar House easily, and used it as a forward supply base, but Blackness was a tougher proposition. Cromwell claimed to have taken it in March, but it held out until April.

All of these mopping up operations took some time, and winter weather also played its part in delaying progress. In the early months of 1651 a stalemate followed. Cromwell fell seriously ill through dysentery; this would affect him greatly until July 1651..

The English army of occupation, low on rations and often without pay in the hard Scottish winter, resorted to widespread plundering and looting.

| < Cromwell invades Scotland | Δ Index | Breaking the Stalemate > |