Military Aviation during WWI – RFC

< Back to Military Aviation round the forth

At the outbreak of WWI, the Royal Flying Corps supported the British Expeditionary forces in France, flying reconnaissance missions, while the Royal Navy Air Service provided air support for several detachments of marines in Belgium.

Reconnaissance aircraft.

At the start of the war, there was some debate over the usefulness of aircraft in warfare. However air reconnaissance played a critical role in the “war of movement” of 1914, especially in helping the Allies halt the German invasion of France. On 22 August 1914, British aircraft reported that a German was preparing to surround the British Expeditionary Force, contradicting all other intelligence. The British High Command took note of the report and withdrew toward Mons, saving the lives of 100,000 soldiers. Later, during the First Battle of the Marne, observation aircraft discovered weak points and exposed flanks in the German lines, allowing the allies to take advantage of them.

By the end of 1914 the line between the Germans and the Allies stretched from the North Sea to the Alps. The initial “war of movement” largely ceased, and the front became static, the focus for aeroplanes shifted to artillery spotting. By March 1915, a two-seater on “artillery observation” duties was typically equipped with a primitive radio transmitter transmitting using Morse code, but had no receiver. The artillery battery signalled to the aircraft by laying strips of white cloth on the ground in prearranged patterns.

Observation balloons

As the ground war settled into stalemate, manned observation balloons floating high above the trenches were used as stationary reconnaissance points on the front lines, reporting enemy troop positions and directing artillery fire. Balloons commonly had a crew of two equipped with parachutes: upon an enemy air attack on the flammable balloon, the crew would parachute to safety. Recognized for their value as observer platforms, observation balloons were important targets of enemy aircraft. To defend against air attack, they were heavily protected by large concentrations of antiaircraft guns and patrolled by friendly aircraft.

Fighter aircraft – introduction and evolution

The success of reconnaissance and artillery spotting led to an arms race to develop single-seater fighter aircraft, with forward firing machine guns that could attack reconnaissance scouts. By late1915 the German Fokkers had achieved air superiority, rendering Allied access to the vital intelligence derived from continual aerial reconnaissance more dangerous to acquire.

Great Britain had “started late” in aircraft development and initially relied largely on the French aircraft industry, especially for aircraft engines. Fortunately, two new British fighters that were a match for the Fokker, the two-seat F.E.2b and the single-seat D.H.2, reached the front in September 1915, and February 1916 respectively. These and the new French Nieuport 11, proved more than a match for the Fokkers and allowed the Allies to re-establish air superiority in time for the Battle of the Somme, (July to November 1916.)

But reconnaissance flying, like all kinds, remained a hazardous business. In April 1917, the worst month for the entire war for the RFC, the average life expectancy of a British pilot on the Western Front was 69 flying hours.

The allied success in 1916 prompted the Germans to completely restructure their air force creating specialist fighter squadrons, strategic bombing squadrons, and ground-support squadrons (that attacked infantry in a land battle with machine guns and light bombs.

At this time, counter fire from the ground was far less effective than it became later, when the necessary techniques of deflection shooting had been mastered.

The new organization and the new Albatros D.III aeroplane swung air superiority back to Germany in first half of 1917 and the much larger RFC suffered significantly higher casualties than their opponents. While new Allied fighters such as the Sopwith Pup, Sopwith Triplane, and SPAD S.VII were coming into service, at this stage their numbers were small, and suffered from inferior firepower: all three were armed with just a single synchronised Vickers machine gun. Meanwhile, most RFC two-seater squadrons still flew the BE.2e, which was fundamentally unsuited to air-to-air combat.

This culminated in the rout of April 1917, known as “Bloody April” when the Royal Flying Corps suffered particularly severe losses.

During the last half of 1917, the British Sopwith Camel and S.E.5a and the French SPAD S.XIII, became available in numbers. On the other hand, the latest Albatros, the D.V, and the Fokker Dr.I proved to be disappointments. By the end of 2017 the air superiority pendulum had swung once more in the Allies’ favour.

The surrender of the Russians in March 1918, released German of troops from the Eastern Front and gave them a “last chance” of winning the war before the Americans could become involved. The resulting “Spring Offensive”, opened on 21 March 1918. The main attack fell on the British front and resulted in deeper penetration than had been achieved since 1914. Many British airfields had to be abandoned to the advancing Germans in a new war of movement. Losses of aircraft and their crew were very heavy on both sides – especially to light anti-aircraft fire.

In the midst of this campaign, the separate British RFC and RNAS air services were consolidated into the Royal Air Force on April 1, 1918, the first independent air arm not subordinate to its national army or navy.

By the end of April 1918, the great offensive had largely stalled. The promised new German fighters, notably the Fokker D.VII, had still not arrived, and the Allied blockade of Germany was causing an increasing shortage of lubricating oil and spare parts – these were often salvaged from captured allied aircraft.

The second half of 1918 saw the increasing involvement of the United States, with all-American squadrons growing in numbers and experience, and being supplied with improved aircraft the twin-gun SPAD XIII, Sopwith Camel and S.E. 5a. By the war’s end, the Americans came to hold their own in the air; although casualties were heavy, as indeed were those of the French and British, in the last desperate fighting of the war. By September 2018 casualties in the RFC had reached the highest level since “Bloody April” – and the Allies were maintaining air superiority by weight of numbers rather than technical superiority.

Bombers

Before WWI, Britain had been concerned about Germany’s lead in airship development. (Britain’s first rigid airship – the Mayfly – broke in two in 1911 when it was mishandled on the ground and the development programme was more or less abandoned.) Concerns were raised that Zeppelins could be used as long-range bombers.

These concerns proved to be well-founded. In the opening weeks of the war Zeppelins bombed Liege, Antwerp and Warsaw, and other cities including Paris and Bucharest were targeted. And in January 1915 the Germans began a bombing campaign against Britain that was to last until 1918.

Gradually British air defences improved. In 1917 and 1918 there were only eleven Zeppelin raids against England, and the final raid occurred on 5 August 1918. By the end of the war, 54 airship raids had been undertaken, in which 557 people were killed and 1,358 injured.

By 1917, both Britain and Germany had developed similar types of bomber aeroplanes.

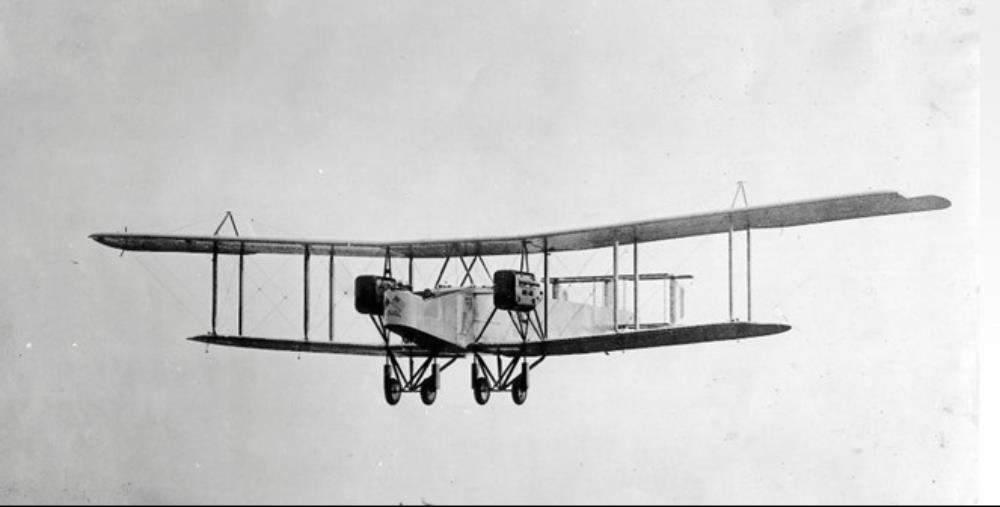

British Handley-Page 0/400 bomber

British Handley-Page 0/400 bomber

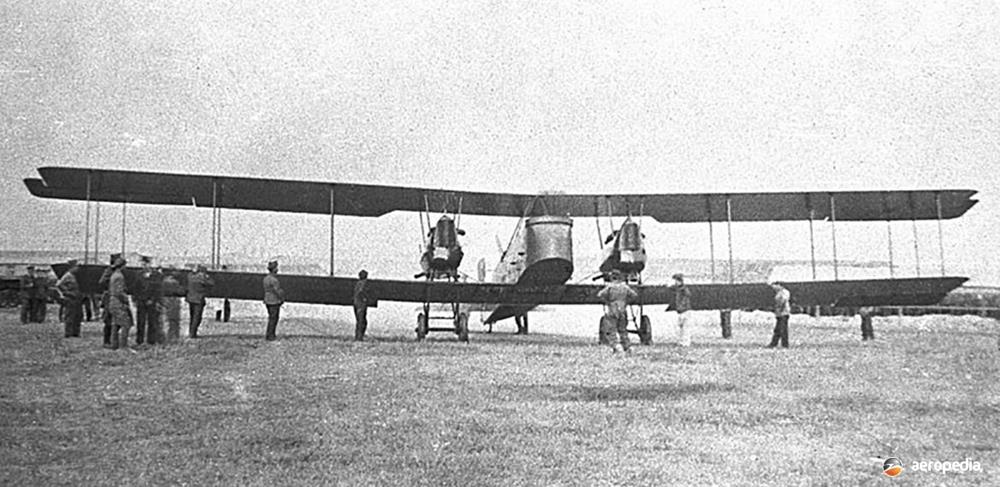

German Gotha G.V bomber

German Gotha G.V bomber

From September 1917 to May 1918, the Zeppelin raids were complemented by the Gotha G bombers and five Zeppelin-Staaken R.VI “giant” four engine bombers from late September 1917 through to mid-May 1918. Twenty-eight Gotha twin-engine bombers were lost on the raids over England, with no losses for the Zeppelin-Staaken giants.