1918 Armistice

The Armistice Process

In August 1916, Paul von Hindenberg was named Germany’s Chief of General Staff, with overall control of the Germany army. As Kaiser Wilhelm II increasingly delegated authority to the military, Hindenberg and his deputy Erich Ludendorff ultimately formed a de facto military dictatorship that dominated German policymaking for the rest of the war.

The United States had joined the Allied Powers in fighting the Central Powers on April 6, 1917.

Its entry into the war had in part been due to Germany’s resumption of submarine warfare against merchant ships trading with France and Britain and also the interception of the Zimmermann Telegram, which had been sent from the German Foreign office to the German Ambassador to Mexico in January 1917.

The telegram proposed a military alliance between Germany and Mexico in the event of the United States entering the war against Germany. Mexico would recover Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico.

The proposal was intercepted and decoded by British intelligence. Revelation of the contents enraged American public opinion, especially after the German Foreign Secretary Arthur Zimmermann publicly admitted the telegram was genuine on March 3.

President Wilson was prepared to go to war to defeat Germany, but wanted to avoid the United States’ involvement in the long-standing European tensions between the great powers.

On January 8, 1918, he made a speech to Congress to sketch out his vision for an end to the war, and the basis for a lasting peace in Europe. This vison was set out in Fourteen Points.

By the summer of 1918, the combined pressure of the Allied blockade and the influx of American troops and equipment made a German defeat inevitable

On 29 September 1918 Hindenberg informed Kaiser Wilhelm II, that the military situation facing Germany was hopeless

Ludendorff, fearing a breakthrough, claimed that he could not guarantee that the front would hold for another two hours and demanded a request be given to the Allied Powers for an immediate ceasefire.

In addition, he recommended the acceptance of the main demands of US president Woodrow Wilson (the Fourteen Points) including putting the Imperial Government on a democratic footing, hoping for more favorable peace terms.

This enabled him to save the face of the German Army and put the responsibility for the capitulation and its consequences squarely into the hands of the democratic parties and the parliament. As he said to officers of his staff on 1 October: “They now must lie on the bed that they’ve made for us.”

On 3 October 2018, the liberal Prince Maximilian of Baden was appointed Chancellor of Germany (prime minister), replacing Georg von Hertling in order to negotiate an armistice.

After long discussions with the Kaiser and evaluations of the political and military situations in Germany, on 5 October 1918 the German government sent a message to President Wilson that they wanted to start to negotiate terms on the basis of the “Fourteen Points”.

As a precondition for negotiations, Wilson demanded the retreat of Germany from all occupied territories, the cessation of submarine activities and the Kaiser’s abdication. The alternative was not peace negotiations but surrender.

In late October, Ludendorff suddenly declared the conditions of the Allies unacceptable. He now demanded to resume the war which he himself had declared lost only one month earlier. However the German soldiers were pressing to get home, and desertions were on the increase.

There was also growing discontent in the Navy. On 29th October, Admiral Hipper issued an order the entire High Seas Fleet to put to sea to have an all-out battle with the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet. This provoked a mutiny among the sailors who felt they were being sacrificed to disrupt the armistice negotiations. The mission was cancelled.

The German Government stayed on course, Ludendorff was replaced by Wilhelm Groener, and peace negotiations continued.

However, the French, British and Italian governments had no desire to accept the “Fourteen Points” and President Wilson’s subsequent promises. They wanted a tougher set of conditions. Germany was to disbanded the army and give up its navy. Allied troops were to occupy the Rhineland. Germany was to pay reparation for damage done and war losses.

On 5th November, the Allies agreed to take up negotiations for a truce, based on these tougher terms.

On 6th November, a German Government delegation headed by Matthias Erzberger departed for France. They crossed the front line in five cars and were escorted for ten hours across the devastated war zone of Northern France, arriving on the morning of 8 November at a secret destination aboard the private train of Marshal Foch, the Allied supreme commander. The train was parked in a railway siding in the forest of Compiègne.

Foch appeared only twice in the three days of negotiations: on the first day, to ask the German delegation what they wanted, and on the last day, to see to the signatures.

The Germans were handed the list of Allied demands and given 72 hours to agree. The German delegation discussed the Allied terms not with Foch, but with other French and Allied officers.

The Armistice amounted to complete German demilitarization (see list below), with few promises made by the Allies in return. The naval blockade of Germany was not to be lifted until complete peace terms could be agreed upon.

There was no question of negotiation. The Germans were able to correct a few impossible demands (for example, the decommissioning of more submarines than their fleet possessed), extended the schedule for the withdrawal and registered their formal protest at the harshness of Allied terms.

But they were in no position to refuse to sign.

On 9th November, Prince Maximilian of Baden handed over the office of Chancellor to Friedrich Ebert

On Sunday 10th November, Ebert instructed Erzberger to sign. The cabinet had earlier received a message from Hindenburg, requesting that the armistice be signed even if the Allied conditions could not be improved on. On the same day they were shown newspapers from Paris to inform them that the Kaiser had abdicated.

The Armistice terms were agreed at 5:00 a.m. on Monday 11th November, to come into effect at 11:00 a.m. Paris time (noon German time), for which reason the occasion is sometimes referred to as “the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month”.

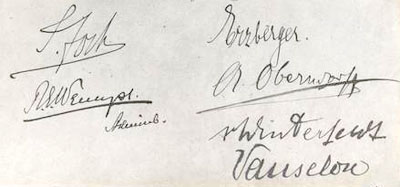

Signatures were made between 5:12 a.m. and 5:20 a.m., Paris time.

For the Allies, the personnel involved were all military. The two signatories were:

Marshal of France Ferdinand Foch, the Allied supreme commander

First Sea Lord Admiral Rosslyn Wemyss, the British representative

Other members of the delegation included:

General Maxime Weygand, Foch’s chief of staff (later French commander-in-chief in 1940)

Rear-Admiral George Hope, Deputy First Sea Lord

Captain Jack Marriott, British naval officer, Naval Assistant to the First Sea Lord

For Germany, the four signatories were:

Matthias Erzberger, a civilian politician.

Count Alfred von Oberndorff, from the Foreign Ministry

Major General Detlof von Winterfeldt, army

Captain Ernst Vanselow, navy

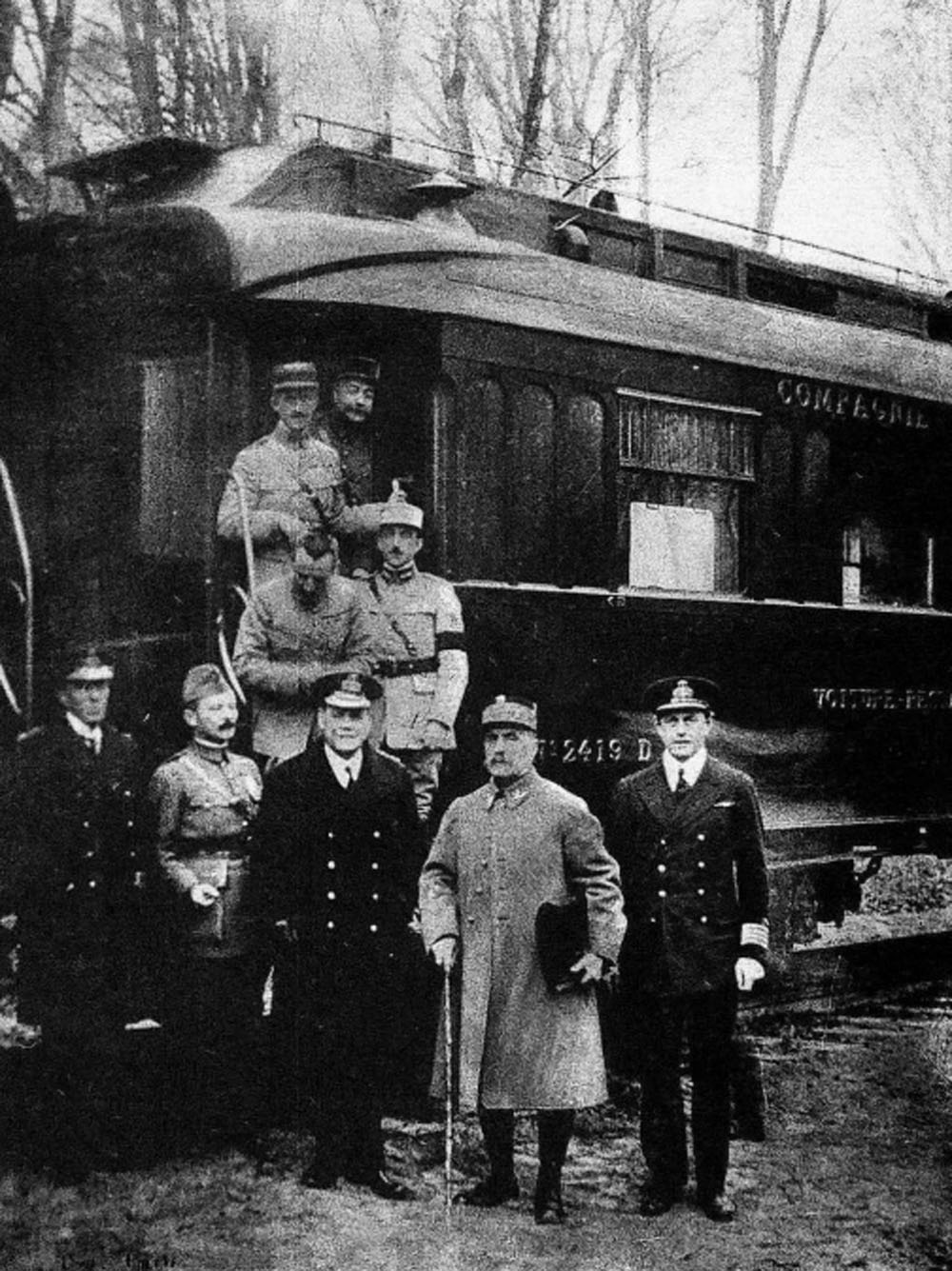

This painting depicts from left to right: Vanselow, von Oberndorff, von Winterfeldt, Marriott Erzberger, Hope, Wemyss, Foch ,and Weygand.

This photograph was taken shortly after the Armistice was signed.

The Armistice.

Among its 34 clauses, the armistice contained the following major points:

A. Western Front

• Termination of hostilities on the Western Front, on land and in the air, within six hours of signature.

• Immediate evacuation of France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Alsace-Lorraine within 15 days. Sick and wounded may be left for Allies to be cared for.

• Immediate repatriation of all inhabitants of those four territories in German hands.

• Surrender of matériel: 5,000 artillery pieces, 25,000 machine guns, 3,000 mine launchers, 1,700 aircraft (including all night bombers), 5,000 railway locomotives, 150,000 railcars and 5,000 road trucks.

• Evacuation of territory on the west side of the Rhine plus 30 km (19 mi) radius bridgeheads of the east side of the Rhine at the cities of Mainz, Koblenz, and Cologne within 31 days.

• Vacated territory to be occupied by Allied and US troops, maintained at Germany’s expense.

• No removal or destruction of civilian goods or inhabitants in evacuated territories and all military matériel and premises to be left intact.

• All minefields on land and sea to be identified.

• All means of communication (roads, railways, canals, bridges, telegraphs, telephones) to be left intact, as well as everything needed for agriculture and industry.

B. Eastern and African Fronts

• Immediate withdrawal of all German troops in Romania and in what were the Ottoman Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Russian Empire back to German territory as it was on 1 August 1914. The Allies to have access to these countries.

• Renunciation of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with Russia and of the Treaty of Bucharest with Romania.

• Evacuation of German forces in Africa.

C. At sea

• Immediate cessation of all hostilities at sea and surrender intact of all German submarines within 14 days.

• Listed German surface vessels to be interned within 7 days and the rest disarmed.

• Free access to German waters for Allied ships and for those of the Netherlands, Norway, Denmark and Sweden.

• The naval blockade of Germany to continue.

• Immediate evacuation of all Black Sea ports and handover of all captured Russian vessels.

D. General

• Immediate release of all Allied prisoners of war and interned civilians, without reciprocity.

• Pending a financial settlement, surrender of assets looted from Belgium, Romania and Russia.

The British public was notified of the armistice at 10:20 am, when British Prime Minister David Lloyd George announced: “The armistice was signed at five o’clock this morning, and hostilities are to cease on all fronts at 11 a.m. to-day.

An official communique was published by the United States at 2:30 pm: “In accordance with the terms of the Armistice, hostilities on the fronts of the American armies were suspended at eleven o’clock this morning.”

News of the armistice being signed was officially announced towards 9 am in Paris.

At 10:50 am, Foch issued this general order: “Hostilities will cease on the whole front as from November 11 at 11 o’clock French time The Allied troops will not, until further order, go beyond the line reached on that date and at that hour.”

Although the information about the imminent ceasefire had spread among the forces at the front in the hours before, fighting in many sections of the front continued right until the appointed hour

On the Allied side, euphoria and exultation were rare. There was some cheering and applause, but the dominant feeling was silence and emptiness after 52 exhausting months of war.

Many artillery units continued to fire on German targets to avoid having to haul away their spare ammunition. The Allies also wished to ensure that, should fighting restart, they would be in the most favourable position. An example of the determination of the Allies to maintain pressure until the last minute, but also to adhere strictly to the Armistice terms, was Battery 4 of the US Navy’s long-range 14-inch railway guns firing its last shot at 10:57:30 am from the Verdun area, timed to land far behind the German front line just before the scheduled Armistice.

Last casualties

Augustin Trébuchon was the last Frenchman to die when he was shot on his way to tell fellow soldiers, who were attempting an assault across the Meuse river, that hot soup would be served after the ceasefire. He was killed at 10:50 am.

The last soldier from the UK to die, George Edwin Ellison of the 5th Royal Irish Lancers, was killed earlier that morning at around 9:30 am while scouting on the outskirts of Mons, Belgium.

The final Canadian, and Commonwealth, soldier to die, Private George Lawrence Price, was shot and killed by a sniper while part of a force advancing into the town of Ville-sur-Haine just two minutes before the armistice to the north of Mons at 10:58 am, to be recognized as one of the last killed with a monument to his name.

And finally, American Henry Gunther is generally recognized as the last soldier killed in action in World War I. He was killed 60 seconds before the armistice came into force while charging astonished German troops who were aware the Armistice was nearly upon them. He had been despondent over his recent reduction in rank and was apparently trying to redeem his reputation.

Treaty of Versailles

Although the Armistice ended the fighting, negotiations continued until The Treaty of Versailles was signed on 28 June 1919.

It came into effect on 10th January 1920.

The Armistice was prolonged three times in that period:

First Armistice (11 November 1918 – 13 December 1918)

First prolongation (13 December 1918 – 16 January 1919)

Second prolongation (16 January 1919 – 16 February 1919)

Third prolongation (16 February 1919 – 10 January 1920)

Paris Peace Conference

The Paris Peace Conference was established on January 18, 1919 to settle the outcome of WWI. It continued until 24 July 1923.

Delegates from 27 nations (delegates representing 5 nationalities were for the most part ignored) were assigned to 52 commissions, which held 1,646 sessions to prepare reports, with the help of many experts, on topics ranging from prisoners of war to undersea cables, to international aviation, to responsibility for the war.

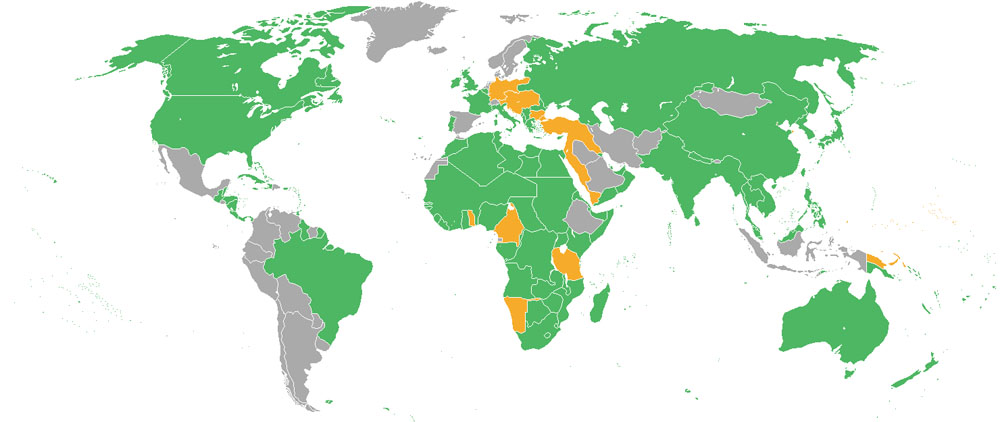

Map of the world with the participants in World War I. The Allies and their colonial possessions are depicted in green, the Central Powers and their colonial possessions in orange, and neutral countries in grey.

The major decisions were the establishment of the League of Nations; the five peace treaties with defeated enemies; the awarding of German and Ottoman overseas possessions as “mandates”, chiefly to members of the British Empire and to France; reparations imposed on Germany, and the drawing of new national boundaries.

The five peace treaties were:

• the Treaty of Versailles, 28 June 1919, (Germany)

• the Treaty of Saint-Germain, 10 September 1919, (Austria)

• the Treaty of Neuilly, 27 November 1919, (Bulgaria)

• the Treaty of Trianon, 4 June 1920, (Hungary)

• the Treaty of Sèvres, 10 August 1920; subsequently revised by the Treaty of Lausanne, 24 July 1923, (Ottoman Empire)

President Wilson became physically ill at the beginning of the conference. This allowed French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau to advance demands in the Treaty of Versailles substantially different from Wilson’s Fourteen Points.

Clemenceau viewed Germany as having unfairly attained an economic victory over France, due to the heavy damage German forces dealt to France’s industries even during the German retreat.

The allies would initially assess 269 billion marks in reparations. In 1921, this figure was established at 192 billion marks. However, only a fraction of this total had to be paid. The figure was designed to look imposing and show the public that Germany was being punished, while it also recognized what Germany could not realistically pay. Germany was also denied an air force, and the German army was not to exceed 100,000 men.

Woodrow Wilson was awarded the 1919 Nobel Peace Prize for his peace-making efforts.